From the late 1830s through the early 1860s, the proslavery argument was at its strongest, in part due to the increasing visibility of the small but vocal abolitionist movement, and in part due to Nat Turner's rebellion in 1831. Among those most famous for propagating the proslavery argument were James Henry Hammond, John C. Calhoun, and William Joseph Harper. The famous "Mudsill Speech" (1858) of James Henry Hammond articulated the proslavery political argument when the ideology was at its most mature.

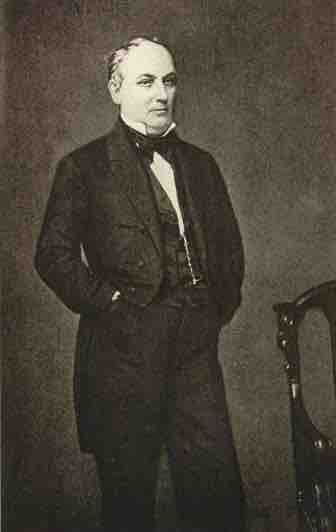

James Henry Hammond

James Henry Hammond's 1858 "Mudsill Speech" argued that slavery would eliminate social ills by eliminating the class of landless poor.

These proslavery theorists championed a class-sensitive view of American antebellum society. They felt that the bane of many past societies was the existence of a class of landless poor. Southern proslavery theorists felt that this class of landless poor was inherently transient and easily manipulated, and as such, often destabilized society as a whole. Thus, the greatest threat to democracy was seen as coming from class warfare that destabilized a nation's economy, society, and government, and threatened the peaceful and harmonious implementation of laws.

This "mudsill theory" supposed that there must be, and has always been, a lower class for the upper classes to rest upon. (The mudsill is the lowest layer that supports the foundation of a building.) James Henry Hammond, a wealthy Southern plantation owner, described this theory to justify what he saw as the willingness of the non-whites to perform menial work: Their labor enabled the higher classes to move civilization forward. In this view, any efforts toward class or racial equality ran counter to this theory and therefore ran counter to civilization itself.

Southern proslavery theorists asserted that slavery prevented any such attempted movement toward equality by elevating all free people to the status of "citizen" and removing the landless poor (the "mudsill") from the political process entirely. That is, those who would most threaten the democratic society's economic stability and political harmony were not allowed to undermine it because they were not allowed to participate in it. In the mindset of proslavery men, therefore, slavery protected the common good of slaves, masters, and society as a whole.

In 1837, John C. Calhoun gave a speech in the U.S. Senate advocating the "positive good" theory of slavery, declaring that slavery was, "instead of an evil, a good—a positive good." Theorists of "positive good" believed that slavery, with its strict and unchanging social hierarchy, made for a more stable society than that of the Northern states, where wage laborers of diverse backgrounds engaged actively in democratic politics.

These arguments asserted the rights of the propertied elite against what were perceived to be threats from abolitionists, lower classes, and non-whites to gain higher standards of living. John C. Calhoun and other pre-Civil War Democrats used these theories in their proslavery rhetoric as they struggled to maintain their grip on the Southern economy. They saw the abolition of slavery as a threat to their new, powerful Southern market, a market that revolved almost entirely around the plantation system and was supported by the use of black slavery.

William Joseph Harper

William Joseph Harper (1790–1847) was a jurist, politician, and social and political theorist from South Carolina. He is best remembered as an early representative of proslavery thought. His "Memoir on Slavery," first given as a lecture in 1838, established Harper as a leading proponent of the notion that slavery was not in fact a necessary evil but rather a positive social good.

Senator William Harper

Senator William Harper is best remembered as an early representative of proslavery thought. He argued that slavery was not in fact a necessary evil but rather a positive social good.

Harper advanced several philosophical, racial, and economic arguments on behalf of slavery, but his central idea was that "slavery anticipates the benefits of civilization and retards the evils of civilization." Harper's assessment of other nations around the world confirmed this point of view. Non-slaveholding civilizations in northern climates, such as Great Britain, were fractured by inequality, political radicalism, and other dangers. Meanwhile, non-slaveholding civilizations in more southerly areas, such as Spain, Italy, and Mexico, were rapidly slipping into "degeneracy and barbarism." Only the slaveholding Southern United States, Brazil, and Cuba were seen as making "favorable progress."

As did nearly every other defender of slavery before 1840, Harper nominally conceded that slavery, at an abstract level, did constitute a sort of (necessary) moral evil. Yet his strong, positive emphasis on the social and economic benefits of the institution separate him from the weaker apologists for slavery of earlier decades.