Loyalists, also known as Tories or Royalists, were American colonists who supported the British monarchy during the American Revolutionary War. During the war, British strategy relied heavily upon the misguided belief that the Loyalist community could be mobilized into Loyalist regiments. Expectations for support were never fully met. In all, about 50,000 Loyalists served as soldiers or militia in the British forces, 19,000 Loyalists were enrolled on a regular army status, and 15,000 Loyalist soldiers and militia came from the Loyalist stronghold of New York.

There was not unanimous support among members of the 13 colonies for the Patriot Siege of Boston (April 19, 1775–March 17, 1776). Widespread corruption among local authorities, many who later became Revolutionary leaders, alienated colonists from the Patriot cause. Colonists in New York, New Jersey, and parts of North and South Carolina were ambivalent about the revolution. Historians estimate that between 15 and 20 percent of European-American colonists supported the Crown; some historians estimate that as much as one third of the population was sympathetic to the British, if not vocally. Americans either remained Loyalists or joined the Patriot cause based on which side they thought would best promote their interests. Prominent merchants in port cities and men with business or family ties to elites in Great Britain tended to favor the Loyalist cause. Nonetheless, people from all socioeconomic backgrounds could be found on both sides.

Loyalism was particularly strong in the Province of Quebec. Although some Canadians took up arms in support of the Patriots, the majority remained loyal to the King. Slaves also contributed to the Loyalist cause, swayed by the promise of freedom following the war. A total of 12,000 African Americans served with the British from 1775 to 1783. The Patriots mirrored this tactic by offering freedom to slaves serving in the Continental Army. Following the war, both sides often reneged on these promises of freedom.

By July 4, 1776, Patriots controlled most of the territory within the 13 colonies and had expelled all royal officials. Colonists who openly proclaimed their loyalty to the Crown were driven from their communities. Loyalists frequently went underground and covertly offered aid to the British. New York City and Long Island were the British military and political bases of operations in North America from 1776 to 1783 and maintained a large concentration of Loyalists, many of whom were refugees from other states. In limited areas where the British had a strong military presence, Loyalists remained in power. For example, during early 1775 in the South Carolina backcountry, Loyalist recruitment outpaced that of the Patriots. Also, from 1779 to 1782, a Loyalist civilian government was re-established in coastal Georgia.

When the Loyalist cause was defeated, however, many Loyalists fled to Britain, Canada, Nova Scotia, and other parts of the British Empire. The departure of royal officials, rich merchants, and landed gentry destroyed the hierarchical networks that thrived in the colonies. Key members of the elite families that owned and controlled much of the commerce and industry in New York, Philadelphia, and Boston left the United States, undermining the cohesion of the old upper class and transforming the social structure of the colonies. The Loyalist exodus also included Ohio Valley farmers who had relied on British military security against Pontiac's armies. Recent non-Anglophone immigrants (especially Germans and Dutch), uncertain of their fate under the new regime, also fled. African American slaves and much of the Mohawk Nation joined the Loyalist migration north and northeast.

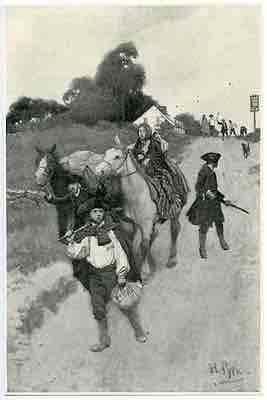

"Tory Refugees on the Way to Canada" by Howard Pyle, 1901

This image from the early 20th century depicts the friction between Loyalist and Patriot sympathizers.