African Americans during the Civil War

The status of African Americans, including escaped slaves from the South, was an issue in flux while the Civil War was being fought. When three slaves presented themselves to Union General Benjamin Butler in 1861 at Fort Monroe, having crossed from Confederate Norfolk County seeking asylum under cover of night, Butler refused to return them to the Confederate Army, where their services were being leased, or to their master who had leased them out. This gave rise to the term “contraband,” a word used to refer to captured enemy property. By August of the same year, Congress determined via the Confiscation Act that the United States would not return escaped slaves to their former Confederate masters. The Union soon utilized former slaves as laborers to support their war efforts and even began to pay them wages for their contributions. The Union also encouraged slave rebellions, urging slaves to undermine the power structure on plantations and flee toward relative freedom. Former slaves set up camps near Union forces, and the army helped support and educate both adults and children among the refugees. Thousands of men from these camps enlisted in the United States Colored Troops (USCT) when recruitment started in 1863.

Grand Contraband Camp

Word spread quickly among southeastern Virginia's slave communities regarding Butler’s actions and Congress’s decision not to return escaping slaves. While becoming a "contraband" did not mean acquiring full freedom, many slaves considered it a step in that direction. The day after Butler's decision, many more escaped slaves found their way to Fort Monroe and appealed for contraband status. As the number of former slaves grew too large to be housed inside the Fort, the contraband slaves erected housing outside of the crowded base from the burned ruins of the City of Hampton. They called their new settlement "Grand Contraband Camp" (which they nicknamed "Slabtown"). By the end of the war in April 1865, less than four years later, an estimated 10,000 escaped slaves had applied to gain contraband status, with many living nearby. Across the South, Union forces managed more than 100 contraband camps, although not all were as large. From a camp on Roanoke Island that started in 1862, Horace James developed the Freedmen's Colony of Roanoke Island (1863–1867). Appointed by the Union Army, James was a Congregational chaplain who, with the freedmen, tried to create a self-sustaining colony at the island.

Outside of the protective walls of Fort Monroe, the pioneering teacher Mary S. Peake began to teach both adult and child contraband slaves to read and write. She was the first black teacher hired by the American Missionary Association, which also sent numerous Northern white teachers to the South to teach. This area of Elizabeth City County later became part of the campus of Hampton University, a historically black college. Defying a Virginia law against educating slaves, Peake and other teachers held classes outdoors under a large oak tree, which later was named the "Emancipation Oak"; in 1863, President Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation was read to the contraband slaves and free blacks there. For most of the contraband slaves, full emancipation did not take place until the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution abolished slavery in late 1865.

As the term itself connoted, contraband slaves were not considered citizens, despite the monumental step toward freedom it represented for the many who sought contraband status. The term added to the ambiguity of many African-Americans’ situations during the Civil War. That uncertainty continued until late 1865, when the Thirteenth Amendment was adopted and contraband slaves became eligible for full emancipation.

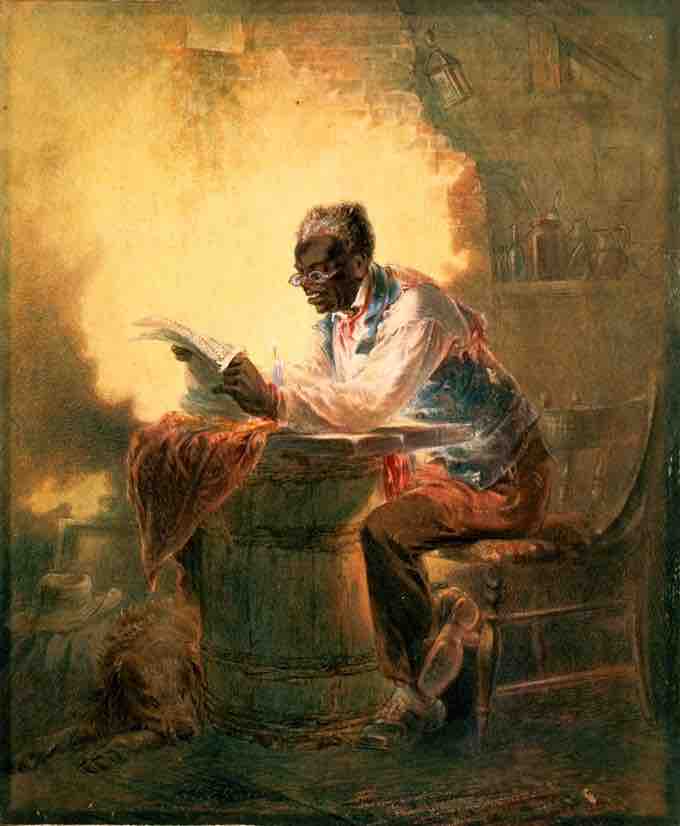

Henry Louis Stephens emancipation watercolor

Henry Louis Stephens's untitled watercolor (ca. 1863) of a man reading a newspaper with the headline, "Presidential Proclamation/Slavery."