An Empire of Liberty: Blue Water Imperialism

The dominant 17th- and 18th-century British imperialist ideology was founded on a liberal conception of freedom and commerce—however, this freedom was only conceptualized in terms of white Anglo-Saxon men. Theoretically, British imperialists envisioned a "blue water empire," in that the British empire stretching across the Atlantic was "Protestant, commercial, maritime, and free." In practice, this meant that British "liberties" and cultural practices were extended to the colonies through overseas trade, weaving the colonies together while forcefully displacing American Indians from their land and building the economy on the exploitation of slave labor.

Protestant Values

Broadly, blue water imperialists aimed to use the power of the metropole to enforce the proper conditions that would allow for commercial and maritime expansion. Therefore, blue water imperial ideology was not necessarily expansionist in terms of acquiring a territorial empire; rather, it aimed for an institutional framework of commercial, international trade in the Atlantic, which the imperialists believed would function as a mechanism for extending British imperial influence to the colonies.

British liberals considered this framework of blue water empire to be anti-despotic—the government sought trade markets abroad in order to extend imperial influence commercially, without arbitrary territorial expansion. Such an empire therefore could not be Catholic because (in the 18th-century Protestant political worldview) Catholics owed allegiance to one ruler, the Pope. The Vatican claimed unlimited spiritual authority over all Catholics, regardless of national identity, which Protestants feared could translate into unlimited political authority as well. Furthermore, Catholicism was the traditional state religion of Spain and France—nations that, according to British liberals, were traditionally ruled by authoritarian, despotic, monarchical power.

British Protestants thus claimed that Catholicism tended to lead to political despotism. They perceived their own religion of Protestantism, on the other hand, to be the religion of liberty. For instance, British liberals viewed their government as the model of Protestant spirit because of its representative legislative body—a parliament that functioned as a check on the authoritarian tendencies of the Crown. British liberals viewed representative government as a hallmark of Protestantism because it counteracted the despotic, authoritarian, and "Catholic" tendencies of monarchy and arbitrary power.

Commercial Values

Blue water empire ideology also hinged on the expansion of international commerce and national wealth. For most 18th-century liberals, commerce was considered to be of utmost importance, rather than territorial expansion. The building of blue water British empire required only human labor and human interaction—large armies were not needed as they were for maintaining territorial acquisitions. Instead, they believed commerce could be conducted peacefully—since it would create a fair market for mutually beneficial trade that required little government interaction.

Furthermore, through overseas commercial markets, British influence would extend rapidly, linking colonies and other nations to British interests without directly occupying foreign territories. Hence, commerce should be an unfettered enterprise: the colonies and the metropole would weave together a common culture and identity through mutual and harmonious trading interests as opposed to conquering foreign territories with expensive armies and engaging in conflict with colonized peoples.

Maritime Policies

Since trade was to be international and mutually beneficial to all Atlantic nations and colonies, blue water empire was thus a maritime project. If the British empire was not going to be based on territorial acquisitions, then it was necessary to control the seas through naval superiority to protect commerce. By definition, blue water empire was an empire of the seas, and the expansion of Britain into the Atlantic was of paramount importance to expanding British trade influences. Hence, for liberals, maritime meant using the navy to establish British superiority over the seas so that commerce and colonization could occur, as they perceived, peacefully. British citizenship and freedoms therefore extended to the Atlantic colonies through British maritime superiority, where merchants could securely exchange goods because of royal naval protection.

Freedom in blue water empire ideology was the defining characteristic that reconciled the inherent tensions between the notion of empire and liberty for 18th-century British liberals. Blue water empire was lauded by its proponents as a non-coercive enterprise because it used the seas as an environment for mutually beneficial commerce, did not seek mass territorial gains and did not require a large standing army to maintain. Liberals believed that through Protestant, commercial, and maritime policies, Britain extended liberties to the Atlantic colonies rather than creating a coercive, territorial empire of (political) "slaves." By using commerce as a vehicle for maritime colonial expansion, Britain extended its values culture to the Atlantic world on a massive scale while simultaneously forging an empire that proclaimed itself as one of liberty.

The Language of Liberty in the Colonies

The American language of liberty is a concept deeply rooted in the Anglo-American colonial experience as well as the American Revolution. It is invoked to describe the fundamental rights of citizens as would be defined in the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. Broadly, the "language of liberty" includes widespread political participation, the duty of the citizen to safeguard against arbitrary despotism, and the right of citizens to life and liberty. Significantly, the language of liberty did not apply to American Indians (who were not considered citizens), women (who were largely considered property of their husbands), and slaves (who were deemed as chattel property).

Colonial Period: Voting, Civic Duty, and Representation

American colonial governments were a local enterprise, with deep roots in a given community and with elected assemblies directly influencing the development of a wide range of public and private businesses. Therefore, Anglo-American colonies were extensive communal cultures, centered on the civic and political sphere. Participation in civic life—through festivals, commemorations, the militia, and court trials—was prevalent, and most free white males in the colonies were expected to partake in some facet of public civic life. Public colonial elections were events in which all free white males were expected to participate in order to demonstrate proper civic pride. Elections became the main forum in which men could publicly profess political allegiances, demonstrating local civic pride to a community that placed high importance on it.

Such widespread participation in local community governments was characteristic solely of the Anglo-American colonies. Compared to Europe, where aristocratic families and the established church were in control, the American political culture was somewhat more open to economic, social, religious, ethnic, and geographical interests.

Slavery and the Language of Liberty

Despite the values inherent in the language of liberty, this language did not apply to slaves, and colonial culture safeguarded American slavery as a fundamental right of white men to their property. As slavery flourished throughout the 18th century, many contemporaries remarked on the institution as a "necessary evil" or a "positive good" to American society and economy. Necessary evil referred to the fear of many whites that if black slaves were emancipated, the social and economic consequences would be more harmful to American liberty than the continuation of slavery. This fear was most prevalent in the aftermath of the Haitian Revolution, when ex-slaves in Haiti massacred their white masters and established a subsistence economy based on peasant proprietorship.

Other pro-slavery advocates claimed that slavery was a "positive good" as it was a beneficial scheme of labor control. This view was embodied in a famous and highly problematic speech by John C. Calhoun. It claimed that in every civilized society one portion of the community must live on the labor of another; learning, science, and the arts are built upon leisure; the African slave, kindly treated by his master and mistress and looked after in his old age, is better off than the free laborers of Europe; and under the slave system, conflicts between capital and labor are avoided.

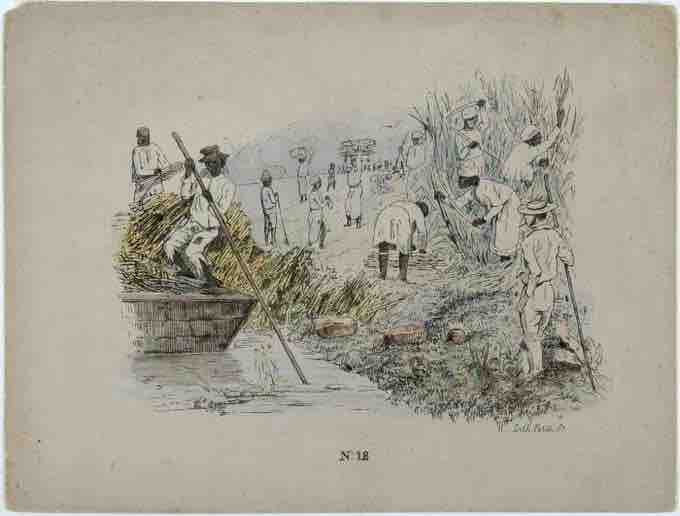

Sugarcane lithograph by Theodore Bray

This 19th century lithograph depicts colonial sugarcane plantations in the Caribbean.