Changing Dynamics

After the Seven Years' War, British troops proceeded to occupy the various forts in the Ohio Country and Great Lakes region that had been previously garrisoned by the French. Even before the war officially ended, the British Crown began to implement changes in order to administer its vastly expanded North American territory. While the French had long cultivated alliances among certain of the American Indian tribes, the British post-war approach was to subordinate the tribes, and tensions quickly rose between the American Indians and the British. The most organized resistance, Pontiac’s Rebellion, highlighted tensions the settler-invaders increasingly interpreted in racial terms.

Pontiac's Rebellion

Tribes Involved

American Indians involved in Pontiac's Rebellion lived in a vaguely defined region of New France known as the pays d'en haut, "the upper country," which was claimed by France until the Treaty of Paris in 1763. The tribes of the pays d'en haut consisted of three basic groups. The first group included the tribes of the Great Lakes region: the Ottawas, Ojibwas, Potawatomis, and Hurons. The second group was made up of the tribes of the eastern Illinois Country, which included the Miamis, Weas, Kickapoos, Mascoutens, and Piankashaws. Both groups had a long-standing peace agreement with the French. The members of the third group were the tribes of the Ohio Country: the Delawares (Lenape), Shawnees, Wyandots, and Mingos. These people had migrated to the Ohio valley earlier in the century in order to escape British, French, and Iroquois domination elsewhere and did not have strong relations with the British or French.

Amherst's Policies Toward American Indians

General Amherst, the British commander-in-chief in North America, was in charge of administering policy toward American Indians, which involved both military matters and regulation of the fur trade. He believed American Indians were militarily weak and thereby subordinate to the British government. One of his policies was to prohibit gift exchange between the American Indians and the British. Once a tradition with the French, gift giving was a symbol of peaceful relations, and the prohibition of such exchanges was interpreted by many American Indians as an insult. Amherst also restricted the American Indians' gun supply, which generated resentment; American Indian men used gunpowder and ammunition to gain food for their families and fur for trade, and by closing off the supply, Amherst imposed hardships on tribal families.

Additional Conflicts

Land was also a motivating factor in the coming of the uprising. While the French population had been low, there seemed to be no end of incoming settler-invaders from England. Shawnees and Delawares in the Ohio Country, especially, had been displaced by British colonists in the east, motivating their resistance along with food shortages and epidemic disease.

The Outbreak of War

Despite previous rumors of war, Pontiac's Rebellion began in 1763. Senecas of the Ohio Country (Mingos) circulated messages calling for the tribes to form a confederacy and drive away the British. The Mingos, led by Guyasuta and Tahaiadoris, were concerned about being surrounded by British-occupied forts. While the rebellion was decentralized at first, this fear of being surrounded helped the rebellion to grow.

The war began at Fort Detroit under the leadership of Ottawa war chief Pontiac and quickly spread throughout the region. Eight British forts were taken. Scholars believe that rather than being planned in advance, the uprising spread as word of Pontiac's actions at Fort Detroit traveled throughout the pays d'en haut, inspiring already discontented American Indians to join the revolt.

The total loss of life resulting from Pontiac's Rebellion is unknown. About 400 British soldiers were killed in action and perhaps 50 were captured and killed; about 2,000 settler-invaders were killed or captured as well. The war compelled approximately 4,000 Pennsylvanian and Virginian settler-invaders to flee their homes. American Indian losses went mostly unrecorded, though it has been estimated that at least 200 warriors were killed in battle.

Foreshadowing of Future Hostilities

Relations between British colonists and American Indians deteriorated further during Pontiac's Rebellion, and the British government concluded that colonists and American Indians must be kept apart. On October 7, 1763, the Crown issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, an effort to reorganize British North America after the Treaty of Paris. Officials drew a boundary line between the British colonies along the seaboard and American Indian lands west of the Appalachian Mountains, creating a vast (and temporary) "Indian Reserve" that stretched from the Appalachians to the Mississippi River and from Florida to Quebec. This boundary was never intended to be permanent, but was rather created as a way to continued British expansion westward in a more organized fashion.

For American Indians, Pontiac's War demonstrated the possibilities of pan-tribal cooperation in resisting Anglo-American colonial expansion. Although the conflict divided tribes and villages, the war also saw the first extensive multi-tribal resistance to European colonization in North America and was the first war between Europeans and American Indians that did not end in complete defeat for the American Indians.

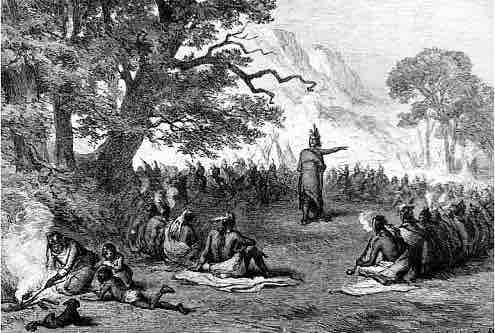

Pontiac's Rebellion

In a famous council on April 27, 1763, depicted in this 19th century engraving by Alfred Bobbet, Pontiac urged listeners rise up against the British.