The Federalist Era

The Federalist Era lasted roughly from 1789 to 1801, when the Federalist Party dominated and shaped American politics. This era saw the adoption of the U.S. Constitution and the growth of a strong centralized government. The period also was characterized by foreign tensions and conflict with France and England, as well as by internal opposition from the rival Democratic-Republicans.

The U.S. Constitution was drafted by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787 and ratified by the majority of the states in 1788, taking effect in 1789. The winning supporters of the ratification of the Constitution were known as Federalists, and the political party later adopted this name. Anti-Federalists, on the other hand, opposed the Constitution in 1788, in part because it lacked a Bill of Rights and because they believed it provided for an overly powerful central government at the expense of state sovereignty and personal liberties.

The Federalist Government and Hamilton's Program

The dynamic force behind the Federalist Party during Washington's presidency was Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton devised a complex, multifaceted program to achieve his vision of a strong centralized government and diverse economy. One of his policies was the assumption of each state's debts from the Revolutionary War. "A national debt," Hamilton concluded, "will be to us a national blessing... powerful cement to our union." He also proposed a novel system of taxes and tariffs to pay for the debt and a Bank of the United States to handle the finances and centralize the fiscal resources of the federal government. Hamilton also designed policies that encouraged manufacturing and commerce, leading to the growth of a wealthy, urban merchant class.

Portrait of Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton is known as the founder of the Federalists.

In order to build support for his program, Hamilton led a coalition anchored by prominent Northeastern businessmen and financiers. This coalition grew into the Federalist Party to express support for a strong central government and to legitimize their claims that they were the true champions of the Constitution. The Federalist-dominated Congress and President Washington approved Hamilton's policies, which broadly interpreted the powers of the federal government under the "necessary and proper" clause of the Constitution.

Opposition from Democratic-Republicans

Hamilton faced mounting opposition from those who claimed that his economic policies favored wealthy commercial interests. Many of Hamilton's opponents believed that his proposed plans went far beyond the powers granted to the federal government by the Constitution. This faction, led by Jefferson and Madison, thus characterized themselves as the legitimate heirs of the American Revolution. They believed that opposition to Hamilton's policies was necessary to prevent the subversion of republican principles. To this end, Jefferson, Madison, and their supporters in Congress began to call themselves Democratic-Republicans.

This party disagreed with the Federalists on both internal and external issues. Democratic-Republicans opposed the Jay Treaty of 1794 with Great Britain and generally supported the French Revolution. Furthermore, Democratic-Republicans adhered to a stricter interpretation of the Constitution and believed that state sovereignty was paramount to the powers of the federal government. Adopting Jefferson's vision of yeoman agriculture as the backbone of the American economy, Democratic-Republicans were suspicious of the primacy of bankers, industrialists, merchants, and other monied interests in Hamilton's economic plans. The party supported states' rights against a potentially tyrannical large centralized government that they feared the Federal government could easily become.

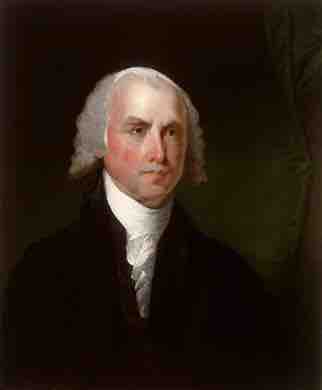

Portrait of James Madison

James Madison was considered the "Father of the Constitution" and was the first author of the Bill of Rights.

Collapse of the Federalist Legacy

The Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798

The decisive event that signaled the collapse of the Federalist party was the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts during the presidency of Federalist John Adams. These acts consisted of a series of legislative "protective" acts that prevented "aliens" with subversive intentions from spreading the insidious elements of the French Revolution to the United States, and headed off "malicious" publications or seditious speeches by Federalist opponents. The Alien and Sedition Acts were denounced by Democratic-Republicans as a direct assault on freedom of speech and the right to organized legislative opposition to the current administration.

Election of Thomas Jefferson

Such resistance to the Alien and Sedition Acts mobilized a great deal of opposition among the electorate, resulting in Adams's defeat in the 1800 election and the first Democratic-Republican presidential administration under Thomas Jefferson. Often referred to as the "Revolution of 1800," this transfer of power from one party to another was the first in American history.

Over the course of his two terms as president—he was reelected in 1804—Jefferson reversed the policies of the Federalist Party by turning away from urban commercial development. Instead, he promoted agriculture through the sale of western public lands in small and affordable lots. Perhaps Jefferson’s most lasting legacy is his vision of an “empire of liberty.” He distrusted cities and instead envisioned a rural republic of land-owning white men, or yeoman republican farmers. He wanted the United States to be the breadbasket of the world, exporting its agricultural commodities without suffering the ills of urbanization and industrialization. Jefferson championed the rights of states and insisted on limited federal government as well as limited taxes.

Hamilton's Death

Jefferson's presidency embodied both Federalist and Democratic-Republican policies that facilitated a peaceful transition of power in this otherwise volatile political period. Despite this relatively peaceful transition, however, the earliest years of the nineteenth century were hardly free of problems between the two political parties. The animosity between the political parties exploded into open violence in 1804, when Aaron Burr, Jefferson’s first vice president, and Alexander Hamilton engaged in a duel. When Democratic-Republican Burr lost his bid for the office of governor of New York, he was quick to blame Hamilton, who had long disliked him and had done everything in his power to discredit him. On July 11, the two antagonists met in Weehawken, New Jersey, to exchange bullets in a duel in which Burr shot and mortally wounded Hamilton. Hamilton's death, in addition to the ascendance of the Democratic-Republicans, hastened the ultimate decline of the Federalist party.