Rutherford B. Hayes

Civil service reform in the United States was a major national issue in the late 1800s and a major state issue in the early 1900s. President Rutherford B. Hayes took office determined to reform the system of civil service appointments, which had been based on the spoils system since Andrew Jackson was president. Instead of giving federal jobs to political supporters, Hayes wished to award them by merit according to an examination that all applicants would take. Immediately, Hayes's call for reform brought him into conflict with the Stalwarts, a pro-spoils branch of the Republican party. Senators of both parties were accustomed to being consulted about political appointments and turned against Hayes. Foremost among his enemies was New York Senator Roscoe Conkling, who fought Hayes's reform efforts at every turn.

To show his commitment to reform, Hayes appointed one of the best-known advocates of reform, Carl Schurz, to be secretary of the Interior and asked Schurz and William M. Evarts, his secretary of state, to lead a special cabinet committee charged with drawing up new rules for federal appointments. John Sherman, the Treasury secretary, ordered John Jay to investigate the New York Custom House, which was stacked with Conkling's spoilsmen. Jay's report suggested that the New York Custom House was so overstaffed with political appointees that 20 percent of the employees were expendable.

Although he could not convince Congress to outlaw the spoils system, Hayes issued an executive order that forbade federal office holders from being required to make campaign contributions or otherwise taking part in party politics. Chester A. Arthur, the collector of the Port of New York, and his subordinates Alonzo B. Cornell and George H. Sharpe, all Conkling supporters, refused to obey the president's order. In September 1877, Hayes demanded the three men's resignations, which they refused to give.

Hayes was forced to wait until July 1878 when, during a Congressional recess, he fired Arthur and Cornell and replaced them through the recess appointments of Merritt and Silas W. Burt, respectively. Conkling opposed the appointees' confirmation when the Senate reconvened in February 1879, but Merritt was approved by a vote of 31 to 25, as was Burt by 31 to 19, giving Hayes his most significant civil service reform victory. For the remainder of his term, Hayes pressed Congress to enact permanent reform legislation, even using his last annual message to Congress on December 6, 1880, to appeal for reform. While reform legislation did not pass during Hayes's presidency, his advocacy provided, "a significant precedent as well as the political impetus for the Pendleton Act of 1883," which was signed into law by President Chester Arthur.

Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act

The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act (ch. 27, 22 Stat. 403) of the United States is a federal law established in 1883 that stipulated that government jobs should be awarded on the basis of merit. The act provided for the selection of government employees based on competitive exams, rather than on ties to politicians or political affiliation. It also made it illegal to fire or demote government employees for political reasons. To enforce the merit system and the judicial system, the law also created the United States Civil Service Commission.

The Pendleton Act served as a response to the massive public support of civil service reform that grew following President Garfield's assassination. Despite his previous support of the patronage system, Arthur, nevertheless, became an ardent supporter of civil service reform as president. However, the law also would prove to be a major political liability for Arthur. The law offended machine politicians within the Republican Party and did not prove to be enough for the party's reformers; hence, Arthur lost popularity within the Republican Party and was unable to win the party's Presidential nomination at the 1884 Republican National Convention.

Postal Service Reform

President Hayes also dealt with corruption in the postal service. In 1880, Schurz and Senator John A. Logan asked Hayes to shut down the "star route" rings, a system of corrupt contract profiteering in the Postal Service, and to fire Second Assistant Postmaster General Thomas J. Brady, the alleged ring leader. Hayes stopped granting new star route contracts, but let existing contracts continue to be enforced. Democrats accused Hayes of delaying proper investigation so as not to injure Republican chances in the 1880 elections but did not press the issue in their campaign literature, as members of both parties were implicated in the corruption. Although Hayes and Congress both looked into the contracts and found no compelling evidence of wrongdoing, Brady and others were indicted for conspiracy in 1882. After two trials, the defendants were found not guilty in 1883.

When Arthur succeeded Garfield, reformers feared that Arthur, as a product of the spoils system, would not devote his administration's energy to continuing the investigation into the Postal Service scandal. However, when a new trial of Brady was granted due to questions of bribery, Arthur removed five federal officeholders who were sympathetic with the defense, including a former senator. The second trial began in December 1882, and lasted until July 1883, but again, did not result in a guilty verdict. Failure to obtain a conviction tarnished the administration's image, but Arthur did succeed in putting a stop to the fraud.

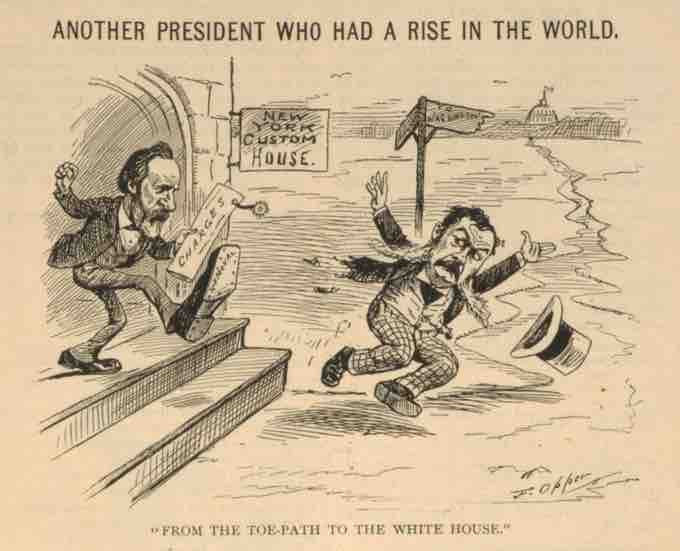

"From the Toe-Path to the White House"

Hayes kicking Chester A. Arthur out of the New York Custom House.