During the Gilded Age, many Americans began working fewer hours and had more disposable income. With newfound money and time to spend on leisure activities, Americans sought new venues for entertainment.

Amusement Parks

Amusement parks, set up outside major cities and in rural areas, emerged to meet this new economic opportunity. These parks reflected the mechanization and efficiency of industrialization while serving as source of fantasy and escape from the realities of working life. By the early 1900s, hundreds of amusement parks were operating in the United States and Canada. Trolley parks, established at the end of the trolley line by enterprising streetcar companies, stood outside of many cities. Parks such as Atlanta's Ponce de Leon and Idora Park near Youngstown, Ohio, took passengers to traditionally popular picnic grounds, which by the late 1890s often included rides such as the carousel, "Giant Swing," and "Shoot-the-Chutes." These amusement parks, with names such as "Coney Island," "White City," "Luna Park," and "Dreamland," often were based on nationally known parks or world's fairs. The American Gilded Age was, in fact, the Golden Age of amusement parks that reigned until the late 1920s.

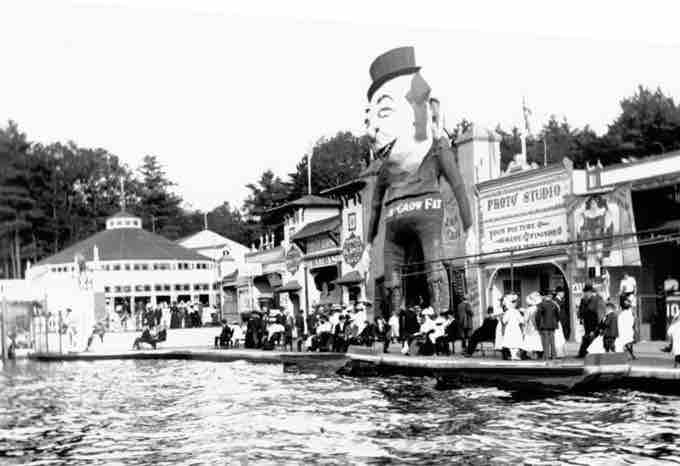

White City Amusement Park

Photograph of the White City Amusement Park, Worcester, Massachusetts, 1908.

By the end of the First World War, people seemed to want an even more exciting entertainment, a need that was met by the roller coaster. Although the development of the automobile provided people with more options for satisfying their need for entertainment, after the war, amusement parks continued to be successful. The 1920s saw the development of many innovations in terms of the roller coaster, which employed extreme drops and speeds to thrill the riders.

Burlesque

American burlesque is a genre of variety show. Derived from elements of Victorian burlesque and music hall and minstrel shows, burlesque shows in America became popular in the 1860s and evolved to feature ribald comedy elements such as lewd jokes and female striptease. By the early twentieth century, burlesque in America was presented as a populist blend of satire, performance art, music hall, and adult entertainment.

Bon-Ton Burlesquers

A poster for an American burlesque show, 1898, showing a woman in an outfit with a low neckline and short skirt holding a number of upper-class men "on the string."

Performers, usually female, often created elaborate tableaux with lush, colorful costumes, mood-appropriate music, and dramatic lighting. Novelty acts, such as fire breathing or contortionists, might be added to enhance the impact of the performance. The genre traditionally encompassed a variety of acts. In addition to the striptease artistes, the show included a combination of chanson singers, comedians, mime artists, and dancing girls, whose performances were all delivered in a satiric style with a impudent edge. The striptease element of burlesque became subject to extensive local legislation, leading to a theatrical form that titillated without falling foul of censors. Burlesque gradually lost popularity beginning in the 1940s. A number of producers sought to capitalize on nostalgia for the entertainment by attempting to recreate the spirit of burlesque in Hollywood films from the 1930s to the 1960s.

Charlie Chaplin, who starred in the 1915 film A Burlesque on Carmen, noted in 1910:

Chicago... had a fierce pioneer gaiety that enlivened the senses, yet underlying it throbbed masculine loneliness. Counteracting this somatic ailment was a national distraction known as the burlesque show, consisting of a coterie of rough-and-tumble comedians supported by twenty or more chorus girls. Some were pretty, others shopworn. Some of the comedians were funny, most of the shows were smutty harem comedies—coarse and cynical affairs.

By the late 1930s, a social crackdown on burlesque shows began their gradual downfall. The shows had slowly changed from ensemble ribald variety performances, to simple performances focusing mostly on the striptease. In New York, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia clamped down on burlesque, effectively putting it out of business by the early 1940s.

Dime Museums

Dime museums were institutions that were briefly popular at the end of the nineteenth century in the United States. Designed as centers for entertainment and moral education for the working class, the museums were distinctly different from upper-middle-class cultural attractions. In urban centers such as New York City, where many immigrants settled, dime museums were popular and cheap entertainment. The dime museum social trend reached its peak during the Progressive Era.

In 1841, P.T. Barnum founded the first dime museum called the "American Museum." P.T. Barnum and Charles Willson Peale introduced their concept of "edutainement," which provided moralistic education through sensational freak shows, theater and circus performances, and many other means of entertainment. The American Museum burned down in 1865 .

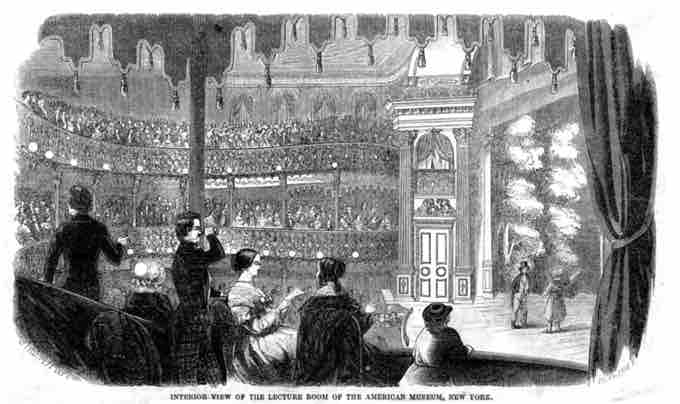

P.T. Barnum's American Museum

The 1853 illustration depicts the "Lecture Room" of the American Museum of New York, built by P. T. Barnum. It was eventually more popularly knows as Barnum's American Museum.

For many years in the basement of the Playland Arcade in Times Square in New York City, Hubert's Museum featured acts such as the sword swallower, Lady Estelene, Congo the Jungle Creep, a flea circus, and a half-man half-woman, and magicians such as Earl "Presto" Johnson. Later, in Times Square, Tommy Laird opened a dime museum that featured Tisha Booty "the Human Pin Cushion," and several magicians including Tommy Laird, Lou Lancaster, Chris Capehart, Dorothy Dietrich, and Dick Brooks.

Vaudeville

Vaudeville was a theatrical genre of variety entertainment popular in the United States and Canada from the 1830s until the early 1930s. Each performance was made up of a series of separate, unrelated acts grouped together on a common bill. Acts included performances by popular and classical musicians, dancers, comedians, trained animals, magicians, impersonators, acrobats, jugglers, athletes, lecturing celebrities, and minstrels. Shows also sometimes featured illustrated songs, one-act plays or scenes from plays, and movies. A vaudeville performer is often referred to as a "vaudevillian." Vaudeville had many influences, including the concert saloon, minstrelsy, freak shows, dime museums, and literary burlesque. Called "the heart of American show business," vaudeville was one of the most popular types of entertainment in North America for several decades.

At its height, vaudeville played to various economic classes and an in a variety of venues. On the vaudeville circuit, it was said that if an act would succeed in Peoria, Illinois, it would work anywhere. The question, "Will it play in Peoria?" has now become a metaphor to indicate whether something appeals to the American mainstream public. The three most common levels of production were the "small time" (lower-paying contracts for more frequent performances in rougher, often converted theaters), the "medium time" (moderate wages for two performances each day in purpose-built theaters), and the "big time" (possible remuneration of several thousand dollars per week in large, urban theaters largely patronized by the middle and upper-middle classes). As performers rose in renown and established regional and national followings, they worked their way into the less arduous working conditions and better pay of the "big time." The capitol of the "big time" was New York City's Palace Theatre (or just "the Palace" in vaudevillian slang). Featuring a bill stocked with inventive novelty acts, national celebrities, and acknowledged masters of vaudeville performance (such as comedian and trick roper Will Rogers), the Palace provided what many vaudevillians considered the apotheosis of remarkable careers.

Vaudeville and Immigrant America

In addition to vaudeville's prominence as a form of American entertainment, it reflected the newly evolving urban inner-city culture. The ethnic caricatures that now composed American humor reflected the positive and negative interactions between ethnic groups in American cities. The caricatures served as a method of understanding different groups and their societal positions.

Making up a large portion of immigration to the United States in the mid-nineteenth century, Irish Americans became subject to discrimination due to their ethnic physical and cultural characteristics. Stereotypical depictions of the Irish as greenhorns alluded to their status as newly arrived immigrants, a portrayal presented in many avenues of entertainment. The use of the "greenhorn immigrant" character for comedic effect showcased not only how immigrants were viewed as new arrivals, but also what they could aspire to be. The Irish-American ideal of transitioning from the "shanty" to the "lace curtain," though often depicted in satire, became a model of economic upward mobility for immigrant groups.