The National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry, commonly called the "Grange," is a fraternal organization for American farmers that encourages farm families to band together for their common economic and political well-being. Founded in 1867 after the Civil War, it is the oldest surviving agricultural organization in America, though now much diminished from the more than one million members it had in its peak in the 1890s through the 1950s. Grange membership has declined considerably as the percentage of American farmers has fallen from a third of the population in the early twentieth century to less than two percent today.

The original objectives of the Grange were primarily educational, but these were soon overborne by an anti-middleman, cooperative movement. Grange agents bought everything from farm machinery to women's dresses, and purchased hundreds of grain elevators, cotton and tobacco warehouses, and even steamboat lines. They formed mutual insurance companies and joint-stock stores. Cooperation was not limited to distributive processes. They purchased patents so that the Grange might manufacture its own farm machinery. In some states, the outcome was ruin, and the name Grange became a reproach. Nevertheless, these efforts in cooperation were exceedingly important both for the results obtained and for their wider significance.

Formation

President Andrew Johnson commissioned Oliver Kelley to go to the Southern states and to collect data to improve Southern agricultural conditions. In the South, poor farmers bore the brunt of the Civil War and were suspicious of Northerners such as Kelley. Kelley found he was able to overcome these sectional differences as a Mason. With Southern Masons as guides, he toured the war-torn countryside in the South and was appalled by the outdated farming practices. He saw the need for an organization that would bring people from the North and South together in a spirit of mutual cooperation, and after many letters and consultations with the other founders, the Grange was born. The first Grange was Grange #1, founded in 1868 in Fredonia, New York.

Political Advocacy

In addition to serving as a center for many farming communities, the Grange was an effective advocacy group for farmers and their agendas, which included fighting railroad monopolies and advocating rural mail deliveries. In the middle of the 1870s, the Granger movement succeeded in regulating the railroads and grain warehouses. The birth of the Cooperative Extension Service, Rural Free Delivery, and the Farm Credit System were largely due to Grange lobbying. The peak of their political power was marked by their success in Munn v. Illinois, which held that the grain warehouses were a, "private utility in the public interest" and therefore could be regulated by public law. However, this achievement was overturned later by the Supreme Court in Wabash v. Illinois.

Other significant Grange causes included temperance, the direct election of senators, and women's suffrage. Susan B. Anthony's last public appearance was at the National Grange Convention in 1903. During the Progressive Era of the 1890s to the 1920s, political parties took up Grange causes. Consequently, local Granger movements focused more on community service, although the state and national Granges remain a political force.

Rituals and Ceremonies

When the Grange first began in 1867, it borrowed from Freemasonry some of its rituals and symbols, including secret meetings, oaths, and special passwords. Small, ceremonial farm tools are often displayed at Grange meetings. Elected officers are in charge of opening and closing each meeting. There are seven degrees of Grange membership. The ceremony of each degree relates to the seasons and various symbols and principles.

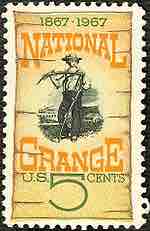

Grange stamp

A 1967 U.S. postage stamp honoring the National Grange.