The Federal Government and the West

The private profit motive dominated the movement westward, but the federal government played a supporting role in securing land through treaties and setting up territorial governments, with governors appointed by the president. The federal government first acquired western territory from other nations or native tribes by treaty, and then it sent surveyors to map and document the land. By the twentieth century, Washington bureaucracies—such as the General Land Office in the Interior Department and, after 1891, the Forest Service in the Department of Agriculture—managed the federal lands. After 1900, dam building and flood control became major concerns.

Transportation was a key issue, and the army, especially the Army Corps of Engineers, was given full responsibility for facilitating navigation on the rivers. The steamboat, first used on the Ohio River in 1811, made inexpensive travel possible using the river systems, especially the Mississippi and Missouri rivers and their tributaries. Army expeditions up the Missouri River in 1818–1825 allowed engineers to improve the technology.

Territorial Governance After the Civil War

With the war over, the federal government focused on improving the governance of the territories. It subdivided several territories, preparing them for statehood, following the precedents set by the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. It standardized procedures and the supervision of territorial governments, taking away some local powers, and imposing much "red tape," growing the federal bureaucracy significantly. Federal involvement in the territories was considerable. In addition to direct subsidies, the federal government maintained military posts, provided safety from Indian attacks, bankrolled treaty obligations, conducted surveys and land sales, built roads, staffed land offices, made harbor improvements, and subsidized overland mail delivery. Territorial citizens came to both decry federal power and local corruption, and at the same time, lament that more federal dollars were not sent their way.

Territorial governors were political appointees and beholden to Washington so they usually governed with a light hand, allowing the legislatures to deal with the local issues. In addition to his role as civil governor, a territorial governor was also a militia commander, a local superintendent of Indian affairs, and the state liaison with federal agencies. The legislatures, on the other hand, spoke for the local citizens, and they were given considerable leeway by the federal government to make local law. These improvements to governance still left plenty of room for profiteering. As Mark Twain wrote in 1913 while working for his brother, the secretary of Nevada, "The government of my country snubs honest simplicity, but fondles artistic villainy, and I think I might have developed into a very capable pickpocket if I had remained in the public service a year or two." Corrupt associations, or "Territorial rings," of local politicians and business owners buttressed with federal patronage, embezzled from Indian tribes and local citizens, especially in the Dakota and New Mexico territories.

In acquiring, preparing, and distributing public land to private ownership, the federal government generally followed the system set forth by the Land Ordinance of 1785. Federal exploration and scientific teams would undertake reconnaissance of the land and determine Native American habitation. Through treaty, land title would be ceded by the resident tribes. Then surveyors would create detailed maps marking the land into squares of six miles on each side, subdivided first into one-square-mile blocks, and then into 160-acre lots. Townships would be formed from the lots and sold at public auction. Unsold land could be purchased from the land office at a minimum price of $1.25 per acre.

As part of public policy, the government would award public land to certain groups such as veterans, through the use of "land scrip." The scrips could be traded in the financial market, often at below the $1.25 per acre minimum price set by law, which gave speculators, investors, and developers another way to acquire large tracts of land cheaply. Land policy became politicized by competing factions and interests, and the question of slavery on new lands was contentious. As a counter to land speculators, farmers formed "claims clubs" to enable them to buy larger tracts than the 160-acre allotments by trading among themselves at controlled prices.

In 1862, Congress passed three important bills that impacted the land system. The Homestead Act granted 160 acres to each settler (whether a citizen or noncitizen, and including squatters and women) who improved the land for five years, for no more than modest filing fees. The law was especially important in the settling of the Plains states, although many farmers purchased their land from railroads at low rates. The Pacific Railway Acts of 1862 provided for the land needed to build the Transcontinental Railroad. The land given to the railroads alternated with government-owned tracts saved for distribution to homesteaders.

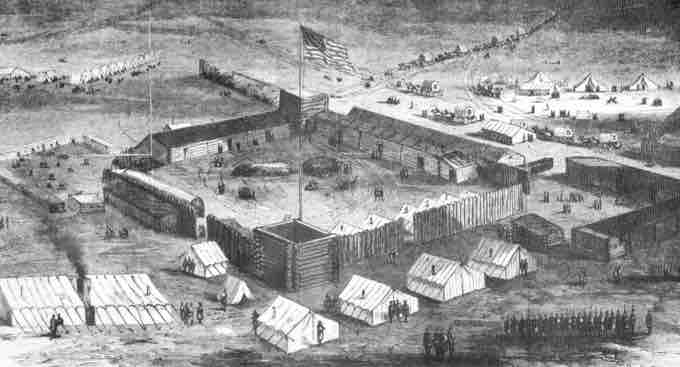

Camp Supply stockade, 1869

This image shows Camp Supply, which was located in Indian Territory (now present-day Oklahoma).