The Market Revolution

During the Market Revolution in the first half of the nineteenth century, traditional modes of commerce were made obsolete by improvements in transportation, communication, and industry. The new technologies and tools that arrived with the Industrial Revolution strengthened large-scale domestic manufacturing in the United States. During this era, Americans began to experience the forces of supply and demand on a broader scale.

New Forms of Labor

Drastic changes in the manual labor system altered the schedules, wages, and working conditions for laborers. Artisanal trades began to give way to more efficient systems of production that did not require skilled labor. Wage labor became an increasingly common experience. Manufacturing came to depend on conveyor belts, interchangeable parts, and industrial tools. The textile industry in New England particularly benefited from these innovations.

New Innovations

Eli Whitney's invention, the cotton gin, helped to establish the new significance of the market to American society, as it enabled southern planters to reap tremendous profits from cotton exports. The large-scale production of cash crops began to replace subsistence farming in the South and West. Simultaneously, port cities such as Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, and Boston developed powerful economies that began to challenge those of contemporary midsize European cities. Americans now could quickly produce larger amounts of goods for a nationwide, and sometimes an international, market and rely less on foreign imports than in colonial times.

Transportation

As American dependency on imports from Europe decreased, the importance of internal commerce increased dramatically. Construction of the Erie Canal connected western agricultural markets to the manufacturing centers of the Northeast, and the development of steamboats and railroads allowed for much greater mobility between markets.

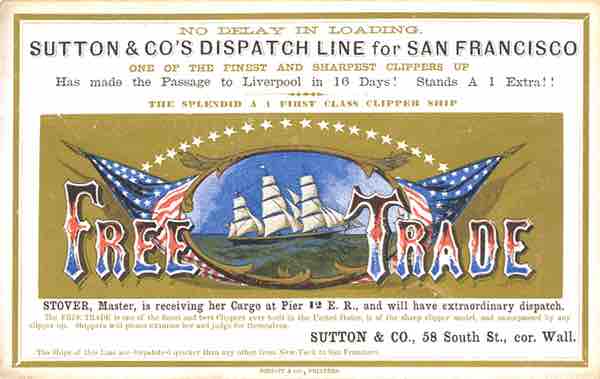

"Free Trade"

Image of an old advertisement from Sutton & Co., with the words "Free Trade" across the front. American society became increasingly subject to broad market forces in the early nineteenth century.