The eastern port cities of Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore transformed the demographic landscape of the United States in the early 1800s. In 1790, only 12 cities in the United States had a population greater than 5,000. By 1860, 16 percent of Americans lived in cities with 2,500 or more people, and manufacturing in these cities was responsible for one-third of the nation's income.

Four Key Urban Centers

Philadelphia

In 1800, Philadelphia was one of the busiest U.S. ports and the country's largest city, with more than 60,000 people living in the city and surrounding area. Philadelphia reigned as the cultural and financial center of the country during this period. Its large free black community aided fugitive slaves and founded the first independent black denomination in the nation, the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

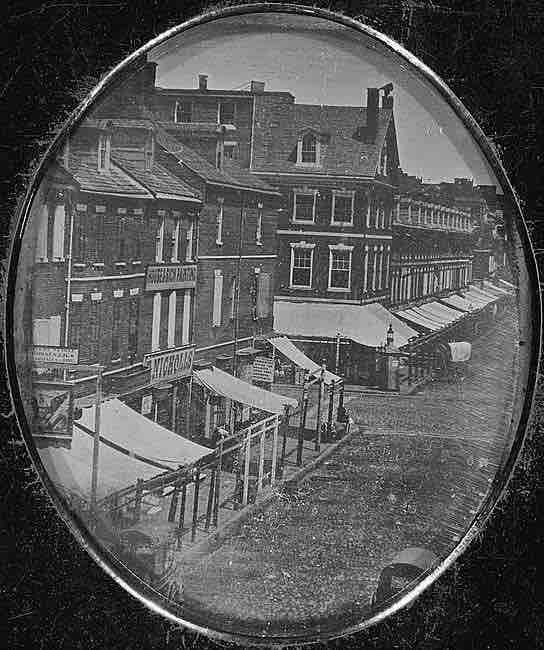

Daguerreotype of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, at the corner of 8th and Market Streets, 1840

Philadelphia was the largest metropolitan center in the United States in the early 1800s.

Philadelphia became one of the first U.S. industrial centers. Major industrial projects included the Waterworks, iron water pipes, a gasworks, and the U.S. Naval Yard. Along with its industrial power, Philadelphia was the financial center of the country. The city was the home of the First and Second Banks of the United States and the first U.S. Mint. Cultural institutions, such as the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the Academy of Natural Sciences, and the Franklin Institute also flourished in Philadelphia.

Philadelphia's maritime trade was interrupted by the Embargo Act of 1807 and the War of 1812. After the war, Philadelphia's shipping industry never returned to its pre-embargo status, and New York City succeeded it as the busiest port and largest city.

New York City

Even in the early nineteenthcentury, New York City was a cosmopolitan enclave with a transitory population made up largely by immigrants. In 1811, New York adopted a grid system of numbered streets and avenues to efficiently develop and sell property in Manhattan.

Overcrowding and unsanitary conditions in New York City contributed to an increase in disease, and cholera and yellow fever ravaged the city. A polluted aquifer, overcrowded housing, a lack of sewers and basic sanitation, and the existence of polluting industries near wells and residential areas contributed to an unprecedented mortality rate. In addition, the rapid expansion of densely packed wooden buildings led to many fires, culminating in the Great Fire of New York in 1835, which devastated the city.

With the development of steamboats and canal routes, waterborne shipments quickly became more popular than shipment over land. The opening of the Erie Canal greatly increased New York City's importance, connecting the city to the vast agricultural markets of the North American interior. Though New York City's rapid development was temporarily suspended by the Panic of 1837, which resulted in high rates of unemployment and bankruptcy for many businesses, the city gradually recovered. By 1850, New York City had reestablished itself as the financial and mercantile capital of the western hemisphere.

The Commissioners' Plan of 1811 provisional map

A drawing of the plans for New York City's grid system, adopted in 1811.

Baltimore

Baltimore grew rapidly in the early nineteenth century, becoming the largest city in the American South. Thanks to the milling technology of Oliver Evans, Baltimore dominated the American flour trade after 1800. Other Baltimore businessmen also contributed to the city's development. Alexander Brown (1764–1834), an Irish immigrant, built the leading foreign exchange house in the United States in the 1830s and the nation's first investment bank. George Peabody (1795–1869) developed an extensive network of financial and mercantile institutions while endowing libraries and museums and aiding the poor. In 1827, Baltimore's merchants and bankers developed the tremendously successful Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

In the late nineteenth century, Baltimore was known as a "city of transients," a fast-growing boomtown attracting thousands of ex-slaves from the surrounding countryside. Slavery in Maryland declined steadily after the 1810s as the state's economy shifted away from plantation agriculture, and a liberal manumission law encouraged slave freedom. Despite the displacement of the black labor force with the arrival of German and Irish immigrants, and increasing poverty in the black community, Baltimore had the largest number of free blacks in the nation on the eve of the Civil War.

Boston

By 1800, Boston was transformed from a relatively small and economically stagnant town to a bustling seaport and cosmopolitan center with a large and highly mobile population. Boston benefited greatly from being an international trading port, exporting rum, fish, salt, and tobacco, among other products. The population approached 25,000 by 1800.

A network of small rivers bordering the city and connecting it to the surrounding region made for easy shipment of goods and allowed for a proliferation of mills and factories. Road networks were constructed to aid transportation, especially of cattle and sheep to markets. By the mid-nineteenth century, an even denser network of railroads facilitated the region's industry and commerce. Boston became one of the largest manufacturing centers in the nation, noted for its garment production, leather goods, and machinery industries.

Effects of the Rise of Urban Centers

Political

Thomas Jefferson and his party of the Democratic-Republicans took issue with what they perceived as favoritism given to commercial classes in the principal American cities. Jefferson thought urban life widened the gap between the wealthy few and an underclass of landless poor workers who, because of their oppressed condition, could never be good republican property owners. Rural areas, in contrast, offered far more opportunities for what Jefferson viewed as property ownership and virtue. Over the course of his two terms as president—from 1800 to 1808—Jefferson reversed the policies of the Federalist Party by turning away from urban commercial development. This shift would not last, however, and future administrations prioritized the growth of urban industry.

The membership of political parties in the Second Party System was reflective of urbanization and wealth. Whigs tended to be wealthier; they were prominent planters in the South and wealthy urban northerners—in other words, the beneficiaries of the market revolution. Democrats presented themselves as defenders of the common people against the elite.

Class and Gender

Members of the emerging business elite in these northern cities forged close ties with one another to protect and expand their economic interests. Marriages between leading families formed a crucial strategy to advance economic advantage, and the homes of the northern elite became important venues for solidifying social bonds. Exclusive neighborhoods started to develop as the wealthy distanced themselves from the poorer urban residents, and cities soon became segregated by class.

The profound economic changes sweeping the United States led to equally important social and cultural transformations. The formation of distinct classes, especially in the rapidly industrializing North, was one of the most striking developments. The unequal distribution of newly created wealth spurred new divisions along class lines.

Urban centers became characterized by working-class families and high rates of poverty. Although most working-class men sought to emulate the middle class by keeping their wives and children out of the work force, their economic situation often necessitated that women and children contribute to the support of the family. Working-class women in urban centers made up a high percentage of the work force, and many working-class children went to work in factories. Many women were wage laborers themselves, and others took in laundry or did piecework at home to supplement the family’s income.