Cotton in the South

In the antebellum era—that is, in the years before the Civil War—American planters in the South continued to grow Chesapeake tobacco and Carolina rice as they had in the colonial era. Cotton, however, emerged as the antebellum South’s major commercial crop, eclipsing tobacco, rice, and sugar in economic importance.

The Cotton Gin

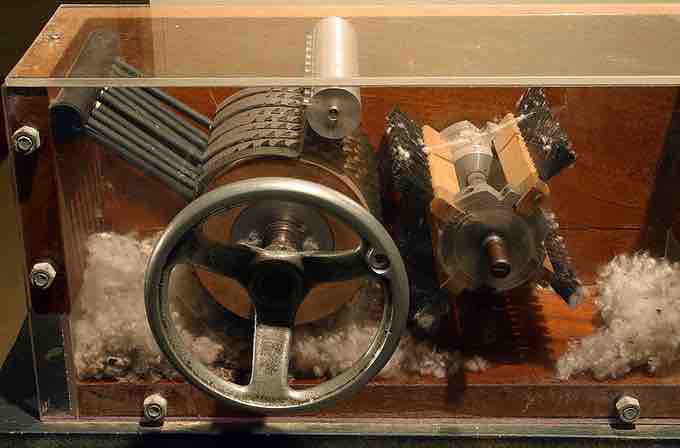

In 1793, Eli Whitney revolutionized the production of cotton when he invented the cotton gin, a device that separated the seeds from raw cotton. Suddenly, a process that was extraordinarily labor-intensive when done by hand could be completed quickly and easily. The cotton gin (short for "cotton engine") quickly and easily separated cotton fibers from their seeds, a job that otherwise had to be performed painstakingly by hand—most often by slaves. Whitney's introduction of "teeth" in his cotton gin to comb out the cotton and separate the seeds revolutionized this process.

With the invention of Whitney's cotton gin, cotton became a tremendously profitable industry, creating many fortunes in the antebellum South. American plantation owners, who were searching for a successful staple crop to compete on the world market, found it in cotton.

A cotton gin on display at the Eli Whitney Museum

The invention of the cotton gin revolutionized the textile industry in the early nineteenth century and transformed the economy of the South.

Domestic and International Markets

As a commodity, cotton had the advantage of being easily stored and transported. A demand for it already existed in the industrial textile mills in Great Britain, and in time, a steady stream of slave-grown American cotton would also supply northern textile mills. Southern cotton, picked and processed by American slaves, helped fuel the nineteenth-century Industrial Revolution in both the United States and Great Britain.

New Orleans, Louisiana, and Galveston, Texas, were shipping points that derived substantial economic benefit from cotton raised throughout the South. Cotton soon became the primary export in the United States, and by 1860, on the eve of the Civil War, the southern states were providing two-thirds of the world's supply of cotton.

Additionally, the development of large-scale mills and metal machine tools dramatically increased textile production in northern mill towns in the early 1800s. Though cotton was primarily grown for export to Europe, this textile boom in New England created an important domestic market for southern cotton producers.

Cotton, Slavery, and the Civil War

Due to its profound effect on American slavery, the growth of the cotton industry is frequently cited as one of the causes of the American Civil War. The number of slaves rose in concert with the increase in cotton production, increasing from approximately 700,000 in 1790 to roughly 3.2 million in 1850. A congressional ban on the importation of slaves from Africa in 1808 only increased the demand for domestic slaves on cotton plantations, hindering the work of abolitionists who sought to end slavery. The domestic slave trade exploded, providing economic opportunities for whites involved in many aspects of the trade and increasing the possibility of slaves’ dislocation and separation from kin and friends.

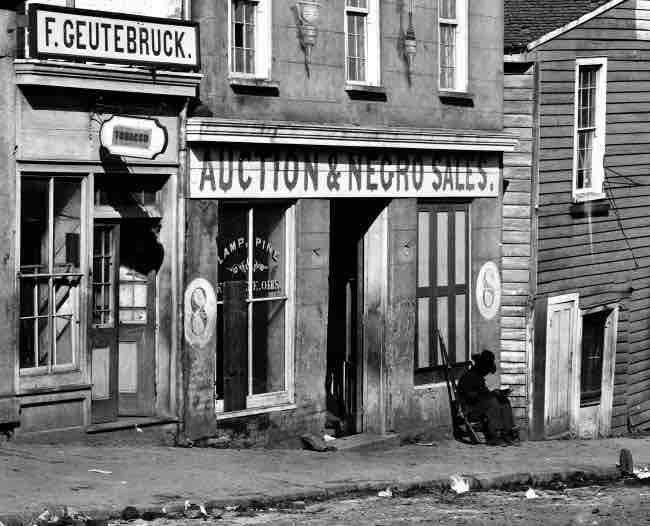

Slave market in Atlanta, Georgia, 1864

This image depicts the site of a slave market in Atlanta in 1864. The cotton industry in the South was fully dependent on the institution of slavery.