The Square Deal

The Square Deal was President Theodore Roosevelt's domestic program. He explained it in the following way in 1910:

When I say that I am for the square deal, I mean not merely that I stand for fair play under the present rules of the game, but that I stand for having those rules changed so as to work for a more substantial equality of opportunity and of reward for equally good service.

His policies reflected three basic ideas: conservation of natural resources, control of corporations, and consumer protection. These three demands often are referred to as the "three Cs" of Roosevelt's Square Deal. Thus, the deal aimed at helping middle-class citizens and involved attacking plutocracy and bad trusts while at the same time protected business from the most extreme demands of organized labor. A Progressive Republican, Roosevelt believed in government action to mitigate social evils, and as president, he denounced in 1908, "the representatives of predatory wealth” as guilty of, "all forms of iniquity from the oppression of wage workers to unfair and unwholesome methods of crushing competition, and to defrauding the public by stock-jobbing and the manipulation of securities." Trusts and monopolies became the primary target of Square Deal legislation.

Control of Corporations

Trusts increasingly became a central issue, as many feared that large corporations would impose monopolistic prices to defraud consumers and drive small, independent companies out. By 1904, 318 trusts including those in railroads, local transit, and the banking industry controlled two-fifths of the nation's industrial output.

One of Roosevelt's first notable acts as president was to deliver a 20,000-word address to Congress asking it to curb the power of large corporations. Despite speaking in support of organized labor (to the further chagrin of big business), he endorsed the gold standard, protective tariffs, and lower taxes (much to the delight of big business). For his aggressive use of U.S. antitrust law, he became known as the "Trust Buster." He brought 40 antitrust suits, and broke up major companies, such as the largest railroad and Standard Oil, the largest oil company.

During both of his terms, Roosevelt tried to extend the Square Deal by pushing the federal courts and Congress to yield to the wishes of the executive branch on all subsequent antitrust suits. An example of this was the Elkins Act, which stated that railroads were no longer allowed to give rebates to favored companies. These rebates had treated small Midwestern farmers unfairly by not allowing them equal access to the services of the railroad. Instead, the Interstate Commerce Commission would control the prices that railroads could charge.

The Hepburn Act authorized the Interstate Commerce Commission to set maximum railroad rates and to stop the practice of giving out free passes to friends of the railway interests. In addition, the Interstate Commerce Commission could examine the railroads' financial records, a task simplified by standardized booking systems. For any railroad that resisted, the Interstate Commerce Commission's conditions would be in effect until a legal decision of a court was issued. Through the Hepburn Act, the Interstate Commerce Commission's authority was extended to bridges, terminals, ferries, sleeping cars, express companies, and oil pipelines.

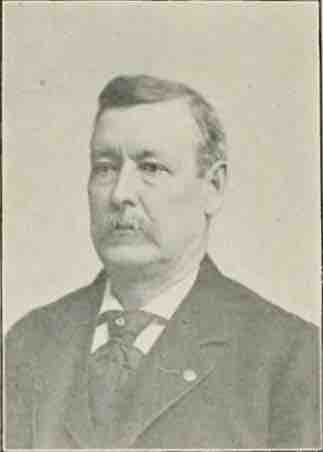

Senator William Peters Hepburn

Photograph of Senator Hepburn, who sponsored the Hepburn Act, which regulated railroad fares, one of the goals of Roosevelt's Square Deal.

1902 Coal Strike

In May 1902, anthracite coal miners went on strike, threatening a national energy shortage. After threatening the coal operators with intervention by federal troops, Roosevelt won their agreement to an arbitration of the dispute by a commission, which succeeded in stopping the strike, dropping coal prices, and retiring furnaces; the accord with J.P. Morgan resulted in the workers getting more pay for fewer hours, but with no union recognition.

Organized labor celebrated the outcome as a victory for the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) and American Federation of Labor unions generally. Membership in other unions soared, as moderates argued that they could produce concrete benefits for workers much sooner than could radical Socialists who planned to overthrow capitalism through revolutionary violence. Furthermore, the outcome of the strike was a success for Roosevelt, who argued that the federal government could successfully intervene in conflicts between labor and capital. Journalist Ray Baker quoted Roosevelt concerning his policy toward capitalists and laborers: "My action on labor should always be considered in connection with my action as regards capital, and both are reducible to my favorite formula—a square deal for every man." The settlement was an important step in the Progressive Era reforms of the decade that followed.

Consumer Protection

Roosevelt responded to public anger over the abuses in the food-packing industry by pushing Congress to pass the Meat Inspection Act of 1906 and the Pure Food and Drug Act. The Meat Inspection Act of 1906 banned misleading labels and preservatives that contained harmful chemicals. The Pure Food and Drug Act banned impure or falsely labeled food and drugs from being made, sold, and shipped. Roosevelt also served as honorary president of the American School Hygiene Association from 1907 to 1908, and in 1909, he convened the first White House Conference on the Care of Dependent Children. The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 and the Meat Inspection Act of 1906 were both widely accredited to Upton Sinclair's The Jungle, which revealed the horrific and unsanitary processes of meat production.

Conservation Efforts

Roosevelt was a prominent conservationist, putting the issue high on the national agenda. He worked with all of the major figures of the movement, especially his chief advisor on the matter, Gifford Pinchot. Roosevelt was deeply committed to conserving natural resources, and is considered to be the nation's first conservation president. He encouraged the Newlands Reclamation Act of 1902 to promote federal construction of dams to irrigate small farms and placed 230 million acres under federal protection. Roosevelt set aside more federal land, national parks, and nature preserves than all of his predecessors combined.

Roosevelt established the United States Forest Service, signed into law the creation of five national parks, and signed the 1906 Antiquities Act, under which he proclaimed 18 new U.S. National Monuments. He also established the first 51 bird reserves, 4 game preserves, and 150 national forests, including Shoshone National Forest, the nation's first. The area of the United States that he placed under public protection totals approximately 230,000,000 acres.