Eugenics was a field sociological and anthropological study that became popular in the late 19th and early 20th century as a method of preserving and improving the population through cultivation of dominant gene groups. Rather than scientific genetics, however, Eugenics is now generally associated with racist and nativist elements who desired so-called "scientific" evidence for prejudicial beliefs and government policies. The Eugenics movement in the United States was used to justify laws enabling forced sterilizations of the mentally ill and prohibiting marriages and child bearing by immigrants, while Eugenics theories were used by the Nazi regime in Germany to justify thousands of sterilizations and, later, widespread murder.

Origins and Proliferation

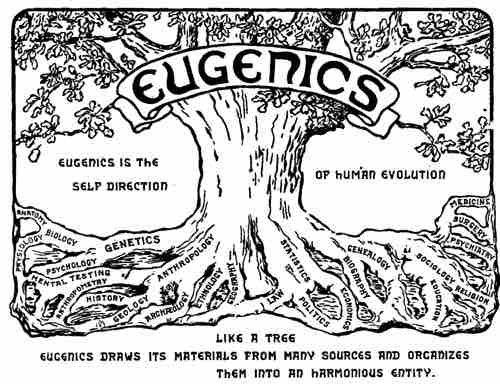

In its time, Eugenics was touted as scientific and progressive, the natural application of knowledge about breeding to the arena of human life. Researchers interested in familial mental disorders conducted studies to document the heritability of such illnesses as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. Rather than true science, though, Eugenics was merely an ill-considered social philosophy aimed at improving the quality of the human population by increasing reproduction between those with genes considered desirable – Nordic, Germanic and Anglo-Saxon peoples – and limiting procreation by those whose genetic stock was seen as less favorable or unlikely to improve the human gene pool. The method considered most viable in attaining this goal was the prevention of marriage and breeding among targeted groups and individuals, but over time the far more extreme action of sterilization became acceptable.

While these ideas existed for centuries, the modern Eugenics movement can be traced to the United Kingdom in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Theory of Evolution made famous by Charles Darwin was used by English sociologist and anthropologist Francis Galton, a half-cousin of Darwin, to promote the idea of a human survival of the fittest that could be enacted through selective breeding. He coined the term Eugenics in 1883 and in 1909 wrote the foreword to the first volume of the Eugenics Review, the journal of the Eugenics Education Society, which named him as its honorary president.

Francis Galton

A half-cousin of Charles Darwin, Francis Galton founded field of Eugenics and promoted the improvement of the human gene pool through selective breeding.

Legitimizing and Legalizing

Eugenicists and supporters began organizing and holding formal discussions and conferences and publishing papers that proliferated through Europe and America. Three International Eugenics Congresses were held between 1912 and 1932, the first taking place in London. Leonard Darwin, son of Charles, presided over the meeting of about 400 delegates from numerous countries – including British luminaries such as the Chief Justice Lord Balfour, and the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill – and served as an indication of the growing popularity of the Eugenics movement.

Second International Eugenics Congress logo, 1921

Eugenics was a popular pseudoscience in the early decades of the 20th century and was promoted through three International Eugenics Congresses between 1912 and 1932.

The American Eugenics movement was rooted in the biological determinist ideas of Galton and included those who believed in genetic superiority of specific Caucasian groups, supported strict immigration and anti-miscegenation laws, and supported the forcible sterilization of the poor, disabled and "immoral."

Both class and race factored into Eugenic definitions of "fit" and "unfit." Using intelligence testing, American Eugenicists asserted that social mobility was indicative of one's genetic fitness. This reaffirmed the existing class and racial hierarchies and explained why the upper to middle class was predominately white, with middle to upper class status being a marker of "superior strains." Eugenicists believed poverty to be a characteristic of genetic inferiority, which meant that that those deemed "unfit" were predominately of the lower classes. Since poverty was associated with prostitution and "mental idiocy," women of the lower classes were the first to be deemed "unfit" and "promiscuous." These women, who were primarily immigrants or women of color, were discouraged from bearing children, and were encouraged to use birth control.

American Eugenics research was funded by distinguished philanthropists and carried out at prestigious universities, trickling down to classrooms where it was presented as a serious science. In 1906, J.H. Kellogg provided funding to help found the Race Betterment Foundation in Battle Creek, Michigan. The Eugenics Record Office (ERO) was founded in Cold Spring Harbor, New York in 1911 by the renowned biologist Charles B. Davenport, using money from both the Harriman railroad fortune and the Carnegie Institution.

Charles Benedict Davenport

American biologist Charles B. Davenport founded the Eugenics Record Office in 1911.

Laws were written in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in America to prohibit marriage and force sterilization of the mentally ill in order to prevent the "passing on" of mental illness to the next generation. The first state to introduce a compulsory sterilization bill was Michigan in 1897, but the proposed law failed to garner enough votes by legislators to be adopted. Eight years later, Pennsylvania's state legislators passed a sterilization bill that was vetoed by the governor. Indiana became the first state to enact sterilization legislation in 1907, followed closely by Washington and California in 1909.

Consequences

Men and women were compulsorily sterilized for different reasons. Men were sterilized to treat their aggression and to eliminate their criminal behavior, while women were sterilized to control the results of their sexuality. Since women bore children, eugenicists held women more accountable than men for the reproduction of the less "desirable" members of society. Eugenicists, therefore, targeted mostly women in their efforts to regulate the birth rate, to "protect" white racial health, and weed out the "defectives" of society.

Sterilization rates across the country were relatively low, California being the exception, until the 1927 Supreme Court case Buck v. Bell that legitimized the forced sterilization of patients at a Virginia home for the mentally retarded. These statutes were not abolished until the mid-20th century, with approximately 60,000 Americans legally sterilized.

Prior to the sterilization ruling in the Supreme Court, eugenicists had already played an important role in government policy by serving as expert advisers on the threat of "inferior stock" from eastern and southern Europe during the Congressional debate over immigration in the early 1920s. This led to passage of the federal Immigration Act of 1924, which reduced the number of immigrants from abroad to 15 percent from previous years.

Harry H. Laughlin

Harry Laughlin served as director of the Eugenics Record Office in Cold Spring Harbor, New York.

There are also direct links between progressive American Eugenicists such as Harry H. Laughlin and racial oppression in Europe. Laughlin wrote the Virginia model statute that was the basis for the Nazi Ernst Rudin's Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring. Before the realization of death camps in World War II, the idea that Eugenics would lead to genocide was not taken seriously by the average American. When Nazi administrators went on trial for war crimes in Nuremberg after the war, however, they justified more than 450,000 mass sterilizations in less than a decade by citing United States Eugenics programs and policies as their inspiration. These sterilizations were the precursor to the Holocaust, the Nazi attempt at genocide against Jews and other ethnic groups they deemed unfavorable to the human gene pool.