During World War I, American farmers made record profits. Agricultural competition from Europe and Russia had disappeared due to the damages of battle and American agricultural goods were shipped around the world. The early 1920s saw a rapid expansion in the American agricultural economy, largely due to new technologies and mechanization. Yet as the decade progressed the agricultural sector did not fare as well as other industries such as automobiles that were seeing a boom through mass production. The U.S. government attempted to help with policies benefiting agriculture, but as foreign countries returned to producing their own food, American goods became overproduced and experienced a drop in prices. This downturn in the rural economy also had a social effect on the farm, with many young workers who had experienced the world beyond their hometowns during the war chose to move to larger towns and cities.

Agricultural Technology

Agriculture became increasingly mechanized in the 1920s with widespread use of the tractor, combine harvester, and other heavy equipment. Information about superior techniques was disseminated through county agents employed by state agricultural colleges and funded by the federal government. The new technologies meant that the most efficient farms were larger in size and more business-oriented firms, hurting the profits of small, family farms that had long been the model in rural America. Despite this increase in farm size and capital intensity, however, the great majority of agricultural production continued to be undertaken by family-owned enterprises.

Financial Burdens

When the war ended, the global food supply increased rapidly as Europe's agricultural market rebounded. Overproduction led to plummeting prices, which led to stagnant market conditions and living standards for farmers in the 1920s. In the United States, hundreds of thousands of farmers had taken out mortgages and loans to buy neighboring properties and were suddenly unable to meet the financial burden. This caused the collapse of land prices after the wartime bubble when farmers used high prices to buy up tracts of land at high prices, saddling them with heavy debts. The agricultural depression grew steadily worse in the middle 1920s while the rest of the economy flourished.

McNary-Haugen Act

Farmers blamed the decline of foreign markets and the effects of the protective tariff for their troubles. Farmers had a powerful voice in Congress and demanded federal subsidies, most notably the McNary-Haugen Farm Relief Act. This legislation, which never became law, was a highly controversial plan to address the concerns of farmers by raising the domestic prices of farm products. The act, which was co-authored by Charles L. McNary (R-Oregon) and Gilbert N. Haugen (R-Iowa), proposed that the government buy overproduced domestic wheat and then either store it or export it to foreign markets at a loss.

McNary and Haugen, 1929

U.S. Senator Charles L. McNary, left, and U.S. Representative Gilbert N. Haugen in 1929. The pair co-authored a bill intended to bolster domestic prices of agricultural goods through government purchase of surpluses for sale overseas. It was never approved.

According to the bill, a federal agency would be created to support and protect domestic farm prices by attempting to maintain price levels that existed before the World War I. By purchasing surpluses and selling them overseas, the federal government would take losses that would be paid for through fees against farm producers. Despite attempts in 1924, 1926, 1927, and 1928 to pass the bill, it was vetoed by President Calvin Coolidge and never approved.

Hoover Plan

Coolidge supported an alternative program put forth by United States Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover and Agriculture Secretary William M. Jardine to modernize farming. The plan was to use more electricity, more efficient equipment, better seeds and breeds, more rural education, and better business practices. Hoover advocated the creation of a Federal Farm Board, which was dedicated to the restriction of crop production within domestic demand, behind a tariff wall, and maintained that the farmers’ ailments were due to defective distribution. The Hoover plan was adopted in 1929, before the October 29 stock market crash.

Commerce Secretary Hoover, 1926

United States Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover, center, in 1926 with his assistants William McCracken, left, and Walter Drake. Hoover became U.S. President in 1929.

Mechanization and Urbanization

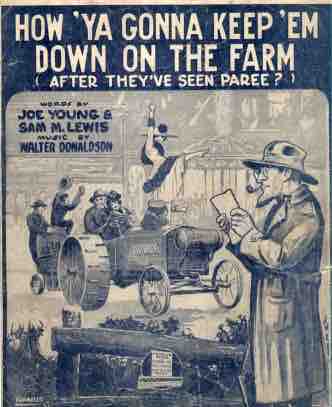

A popular Tin Pan Alley song of 1919 asked a question with unintended economic ramifications about United States troops returning from World War I: "How Ya Gonna Keep 'Em Down On the Farm After They've Seen Paree?" In fact, many did not remain down on the farm and instead became part of a great migration of youth from farms to nearby towns and smaller cities. Some of this could be attributed to a desire for something more adventurous than rural life after seeing some of the culture capitals of Europe, but the migration was also driven by factors such as farm mechanization.

Sheet Music Cover, 1919

A popular song titled, “How ‘Ya Gonna Keep ‘Em Down on the Farm (After They’ve Seen Paree?)” addressed the postwar climate for returning soldiers who had been exposed to culture that may have differed greatly than what they experienced growing up in rural America.

In terms of maintaining the rural population, mechanization proved to be a double-edged sword. By improving production efficiency, mechanization through heavy machinery such as tractors and harvesters improved the quality of produce and made the farms more profitable. On the other hand, mechanization displaced unskilled farm laborers who were no longer needed in the same numbers. This was a direct cause and effect in terms of farmers migrating to urban areas even before the economic devastation of the Great Depression that came after 1929.