The nation needed to turn from a wartime climate to domestic peace following the war. The Wilson administration did not fully plan for the process of demobilization following the war and even with some advisers attempting to direct the president's attention to "reconstruction," his tepid support for a federal commission to oversee the change evaporated after the election of 1918. Combined with a major recession, labor strikes and social upheaval including race riots, this became a difficult time for the nation.

Economic Upheaval

Demobilization proved chaotic and violent. Rather than consenting to the appointment of commission members to counter Republican gains in the Senate, Wilson favored the prompt dismantling of wartime boards and regulatory agencies. The military discharged 4 million soldiers with little planning or money and few benefits. A wartime bubble in farm prices burst, leaving many farmers bankrupt or deeply in debt after purchasing new land. Major strikes in the steel, coal and meatpacking industries followed in 1919.

An economic recession hit much of the world in the aftermath of World War I. In many countries, especially those in North America, growth was continual during the war as nations mobilized their economies. After the war ended, however, the global economy began to decline. In the United States, 1918–1919 included a modest economic retreat, but the next year saw a mild recovery. Yet a more severe recession hit the United States in 1920 and 1921 when the global economy as a whole fell sharply.

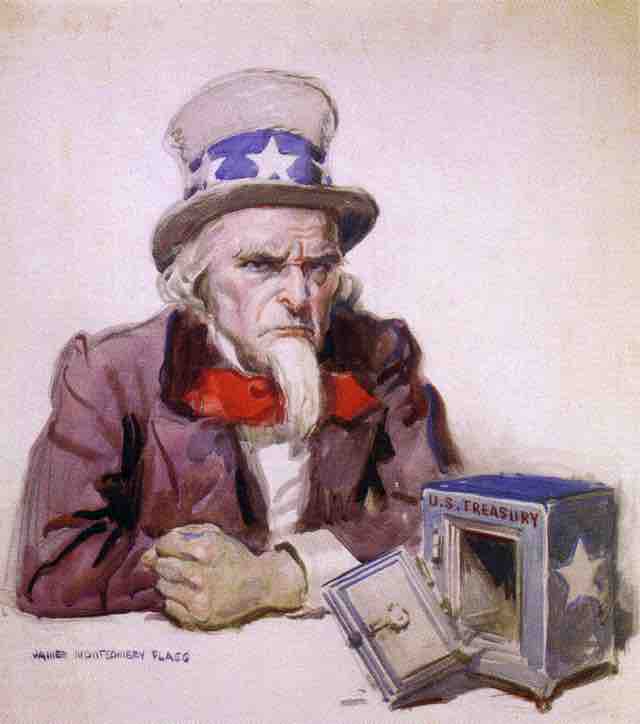

Uncle Sam, Penniless

This political cartoon, drawn in 1920, shows the impact of the war on America's economy.

Labor and Race Tensions

Rapid demobilization of the military had occurred without plans to absorb veterans, both black and white. With the manpower mobilization of World War I and immigration from Europe cut off, the industrial cities of the American North and Midwest experienced severe labor shortages. Along with the removal of price controls, unemployment and inflation soared. Northern manufacturers recruited throughout the South and an exodus of workers and their families ensued. By 1919, an estimated 500,000 southern African-Americans emigrated to the industrial cities of the North and Midwest in the first wave of the so-called Great Migration, which continued until 1940.

Anti-Labor Union Sentiment

The organized labor force during the 1920s also suffered a great deal. The country was fearful of the spread of Communism in America, partly due to the violent overthrow of the government in Russia by Communists, and public opinion hardened against workers who attempted to disrupt the order of the working class. The public was so anti-labor union that in 1922, the Harding administration was able to procure a court injunction to destroy a railroad strike of about 400,000 workers. That same year, the government took part in ending a nationwide strike comprising about 650,000 miners. The federal and state governments had no toleration for strikes and allowed businesses to sue unions for any fiscal damages that occurred during a strike.