INTRODUCTION

The foundations of the British Empire were laid when England and Scotland were separate kingdoms. In 1496, King Henry VII of England, following the successes of Spain and Portugal in overseas exploration, commissioned John Cabot (Venetian born as Giovanni Caboto) to lead a voyage to discover a route to Asia via the North Atlantic. Spain put limited efforts into exploring the northern part of the Americas as its resources were concentrated in Central and South America where more wealth had been found. Cabot sailed in 1497, five years after Europeans reached America, and although he successfully made landfall on the coast of Newfoundland (mistakenly believing, like Christopher Columbus, that he had reached Asia), there was no attempt to found a colony. Cabot led another voyage to the Americas the following year but nothing was heard of his ships again.

THE EARLY EMPIRE

No further attempts to establish English colonies in the Americas were made until well into the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, during the last decades of the 16th century. In the meantime the Protestant Reformation had turned England and Catholic Spain into implacable enemies. In 1562, the English Crown encouraged the privateers John Hawkins and Francis Drake to engage in slave-raiding attacks against Spanish and Portuguese ships off the coast of West Africa with the aim of breaking into the Atlantic trade system. Drake carried out the second circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition, from 1577 to 1580, and was the first to complete the voyage as captain while leading the expedition throughout the entire circumnavigation. With his incursion into the Pacific, he inaugurated an era of privateering and piracy in the western coast of the Americas—an area that had previously been free of piracy.

In 1578, Elizabeth I granted a patent to Humphrey Gilbert for discovery and overseas exploration. That year, Gilbert sailed for the West Indies with the intention of engaging in piracy and establishing a colony in North America, but the expedition was aborted before it had crossed the Atlantic. In 1583, he embarked on a second attempt, on this occasion to the island of Newfoundland whose harbor he formally claimed for England, although no settlers were left behind. Gilbert did not survive the return journey to England, and was succeeded by his half-brother, Walter Raleigh, who was granted his own patent by Elizabeth in 1584. Later that year, Raleigh founded the colony of Roanoke on the coast of present-day North Carolina, but lack of supplies caused the colony to fail.

EMPIRE IN THE AMERICAS

In 1603, James VI, King of Scots, ascended (as James I) to the English throne and in 1604 negotiated the Treaty of London, ending hostilities with Spain. Now at peace with its main rival, English attention shifted from preying on other nations' colonial infrastructures to the business of establishing its own overseas colonies. The Caribbean initially provided England's most important and lucrative colonies. Colonies in Guiana, St Lucia, and Grenada failed but settlements were successfully established in St. Kitts (1624), Barbados (1627) and Nevis (1628). The colonies soon adopted the system of sugar plantations, successfully used by the Portuguese in Brazil, which depended on slave labor, and—at first—Dutch ships, to sell the slaves and buy the sugar. To ensure that the increasingly healthy profits of this trade remained in English hands, Parliament decreed in 1651 Navigation Acts that only English ships would be able to ply their trade in English colonies. In 1655, England annexed the island of Jamaica from the Spanish, and in 1666 succeeded in colonizing the Bahamas.

African slaves working in 17th-century Virginia (tobacco cultivation), by an unknown artist, 1670.

In 1672, the Royal African Company was inaugurated, receiving from King Charles a monopoly of the trade to supply slaves to the British colonies of the Caribbean. From the outset, slavery was the basis of the British Empire in the West Indies and later in North America. Until the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, Britain was responsible for the transportation of 3.5 million African slaves to the Americas, a third of all slaves transported across the Atlantic.

The introduction of Navigation Acts led to war with the Dutch Republic. In the early stages of this First Anglo-Dutch War (1652–1654), the superiority of the large, heavily armed English ships was offset by superior Dutch tactical organisation. English tactical improvements resulted in a series of crushing victories in 1653, bringing peace on favorable terms. This was the first war fought largely, on the English side, by purpose-built, state-owned warships. After the English monarchy was restored in 1660, Charles II re-established the Navy, but from this point on, it ceased to be the personal possession of the reigning monarch, and instead became a national institution – with the title of "The Royal Navy."

England's first permanent settlement in the Americas was founded in 1607 in Jamestown, led by Captain John Smith and managed by the Virginia Company. Bermuda was settled and claimed by England as a result of the 1609 shipwreck there of the Virginia Company's flagship. The Virginia Company's charter was revoked in 1624 and direct control of Virginia was assumed by the crown, thereby founding the Colony of Virginia. In 1620, Plymouth was founded as a haven for puritan religious separatists, later known as the Pilgrims. Fleeing from religious persecution would become the motive of many English would-be colonists to risk the arduous trans-Atlantic voyage: Maryland was founded as a haven for Roman Catholics (1634), Rhode Island (1636) as a colony tolerant of all religions and Connecticut (1639) for Congregationalists. The Province of Carolina was founded in 1663. With the surrender of Fort Amsterdam in 1664, England gained control of the Dutch colony of New Netherland, renaming it New York. In 1681, the colony of Pennsylvania was founded by William Penn. The American colonies were less financially successful than those of the Caribbean, but had large areas of good agricultural land and attracted far larger numbers of English emigrants who preferred their temperate climates.

From the outset, slavery was the basis of the British Empire in the West Indies. Until the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, Britain was responsible for the transportation of 3.5 million African slaves to the Americas, a third of all slaves transported across the Atlantic. In the British Caribbean, the percentage of the population of African descent rose from 25% in 1650 to around 80% in 1780, and in the 13 Colonies from 10% to 40% over the same period (the majority in the southern colonies). For the slave traders, the trade was extremely profitable, and became a major economic mainstay.

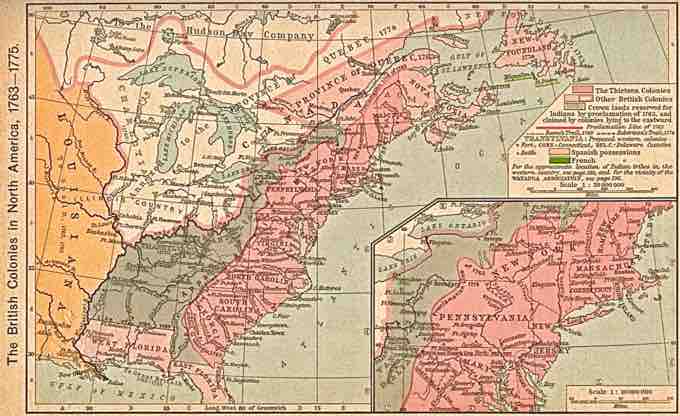

Map of the British colonies in North America, 1763 to 1775. First published in: Shepherd, William Robert (1911) "The British Colonies in North America, 1763–1765" in Historical Atlas, New York, United States: Henry Holt and Company, p. 194.

Although Britain was relatively late in its efforts to explore and colonize the New World, lagging behind Spain and Portugal, it eventually gained significant territories in North America and the Caribbean.