NATURAL RIGHTS AND NATURAL LAW

Natural rights are usually juxtaposed with the concept of legal rights. Legal rights are those bestowed onto a person by a given legal system (i.e., rights that can be modified, repealed, and restrained by human laws). Natural rights are those that are not dependent on the laws, customs, or beliefs of any particular culture or government, and are therefore universal and inalienable (i.e., rights that cannot be repealed or restrained by human laws). Natural rights are closely related to the concept of natural law (or laws). During the Enlightenment, the concept of natural laws was used to challenge the divine right of kings and became an alternative justification for the establishment of a social contract, positive law, and government – and thus legal rights – in the form of classical republicanism (built around concepts such as civil society, civic virtue and mixed government). Conversely, the concept of natural rights is used by others to challenge the legitimacy of all such establishments.

The idea of natural rights is also closely related to that of human rights: some acknowledge no difference between the two, while others choose to keep the terms separate to eliminate association with some features traditionally associated with natural rights. Natural rights, in particular, are considered beyond the authority of any government or international body to dismiss.

NATURAL RIGHTS AND SOCIAL CONTRACT

Although natural rights have been discussed since antiquity, it was the philosophers of the Age of Enlightenment that developed the modern concept of natural rights that has been critical to the modern republican government and civil society. At the time, natural rights developed as part of the social contract theory that addressed the questions of the origin of society and the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual. Social contract arguments typically posit that individuals have consented, either explicitly or tacitly, to surrender some of their freedoms and submit to the authority of the ruler or magistrate (or to the decision of a majority), in exchange for protection of their remaining rights. The question of the relation between natural and legal rights, therefore, is often an aspect of social contract theory.

Thomas Hobbes' conception of natural rights extended from his conception of man in a "state of nature." He argued that the essential natural (human) right was "to use his own power, as he will himself, for the preservation of his own Nature; that is to say, of his own Life." Hobbes sharply distinguished this natural "liberty" from natural "laws." In his natural state, according to Hobbes, man's life consisted entirely of liberties and not at all of laws. He objected to the attempt to derive rights from "natural law," arguing that law ("lex") and right ("jus") though often confused, signify opposites, with law referring to obligations, while rights refer to the absence of obligations. Since by our (human) nature, we seek to maximize our well being, rights are prior to law, natural or institutional, and people will not follow the laws of nature without first being subjected to a sovereign power, without which all ideas of right and wrong are meaningless.

Thomas Hobbes by John Michael Wright, National Portrait Gallery, London.

Thomas Hobbes' 1651 book Leviathan established social contract theory, the foundation of most later Western political philosophy. Though on rational grounds a champion of absolutism for the sovereign, Hobbes also developed some of the fundamentals of European liberal thought: the right of the individual; the natural equality of all men; the artificial character of the political order (which led to the later distinction between civil society and the state); the view that all legitimate political power must be "representative" and based on the consent of the people; and a liberal interpretation of law which leaves people free to do whatever the law does not explicitly forbid.

The most famous natural right formulation comes from John Locke in his Second Treatise, when he introduces the state of nature. For Locke, the law of nature is grounded on mutual security, or the idea that one cannot infringe on another's natural rights, as every man is equal and has the same inalienable rights. These natural rights include perfect equality and freedom and the right to preserve life and property. Such fundamental rights could not be surrendered in the social contract. Another 17th-century Englishman, John Lilburne (known as Freeborn John) argued for level human basic rights he called "freeborn rights" which he defined as being rights that every human being is born with, as opposed to rights bestowed by government or by human law. The distinction between alienable and unalienable rights was introduced by Francis Hutcheson, who argued that "Unalienable Rights are essential Limitations in all Governments.” In the German Enlightenment, Georg Hegel gave a highly developed treatment of the inalienability argument. Like Hutcheson, he based the theory of inalienable rights on the de facto inalienability of those aspects of personhood that distinguish persons from things. A thing, like a piece of property, can in fact be transferred from one person to another. According to Hegel, the same would not apply to those aspects that make one a person. Consequently, the question of whether property is an aspect of natural rights remains a matter of debate.

Thomas Paine further elaborated on natural rights in his influential work Rights of Man (1791), emphasizing that rights cannot be granted by any charter because this would legally imply they can also be revoked and under such circumstances they would be reduced to privileges.

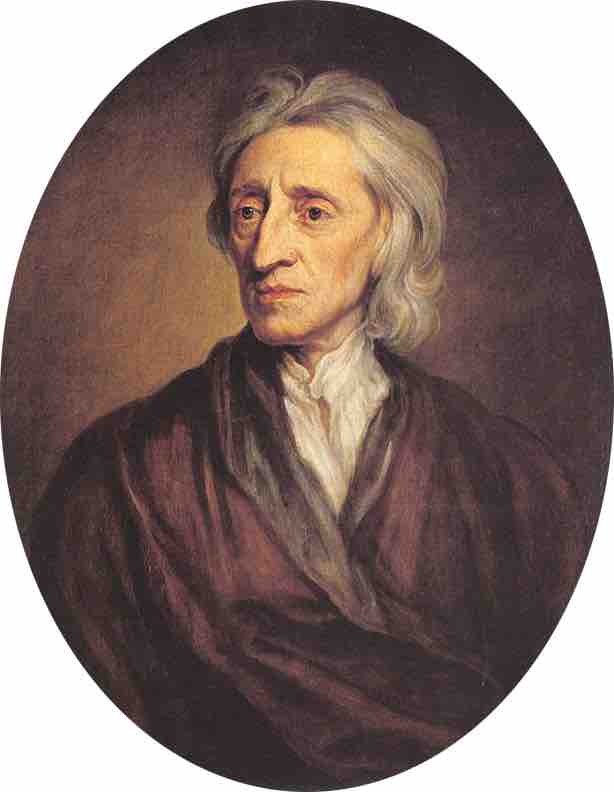

Portrait of John Locke, by Sir Godfrey Kneller, Britain, 1697, State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

The most famous natural right formulation comes from John Locke in his Second Treatise. For Locke, the natural rights include perfect equality and freedom, and the right to preserve life and property.

NATURAL RIGHTS, SLAVERY, AND ABOLITIONISM

In discussion of social contract theory, "inalienable rights" were those rights that could not be surrendered by citizens to the sovereign. Such rights were thought to be natural rights, independent of positive law. Some social contract theorists reasoned, however, that in the natural state only the strongest could benefit from their rights. Thus, people form an implicit social contract, ceding their natural rights to the authority to protect the people from abuse, and living henceforth under the legal rights of that authority.

Many historical apologies for slavery and illiberal government were based on explicit or implicit voluntary contracts to alienate any natural rights to freedom and self-determination. Locke argued against slavery on the basis that enslaving yourself goes against the law of nature: you cannot surrender your own rights, your freedom is absolute and no one can take it from you. Additionally, Locke argues that one person cannot enslave another because it is morally reprehensible, although he introduces a caveat by saying that enslavement of a lawful captive in time of war would not go against one's natural rights. The de facto inalienability arguments of Hutcheson and his predecessors provided the basis for the anti-slavery movement to argue not simply against involuntary slavery but against any explicit or implied contractual forms of slavery. Any contract that tried to legally alienate such a right would be inherently invalid. Similarly, the argument was used by the democratic movement to argue against any explicit or implied social contracts of subjection by which a people would supposedly alienate their right of self-government to a sovereign.