THE RENAISSANCE AND MEDICAL SCIENCES

The Renaissance brought an intense focus on varied scholarship to Christian Europe. A major effort to translate the Arabic and Greek scientific works into Latin emerged and Europeans gradually became experts not only in the ancient writings of the Romans and Greeks but also in the contemporary writings of Islamic scientists. During the later centuries of the Renaissance, which overlapped with the Scientific Revolution, experimental investigation, particularly in the field of dissection and body examination, advanced the knowledge of human anatomy. Other developments of the period also contributed to the modernization of medical research, including printed books that allowed for a wider distribution of medical ideas and anatomical diagrams, more open attitudes of Renaissance humanism, and the Church's diminishing impact on the teachings of the medical profession and universities. In addition, the invention and popularization of microscope in the 17th century greatly advanced medical research.

HUMAN ANATOMY

The writings of ancient Greek physician Galen had dominated European thinking in medicine. Galen's understanding of anatomy and medicine was principally influenced by the then-current theory of humorism (also known as the four humors - black bile, yellow bile, blood, and phlegm), as advanced by ancient Greek physicians such as Hippocrates. His theories dominated and influenced Western medical science for more than 1,300 years. His anatomical reports, based mainly on dissection of monkeys and pigs, remained uncontested until 1543, when printed descriptions and illustrations of human dissections were published in the seminal work De humani corporis fabrica by Andreas Vesalius, who first demonstrated the mistakes in the Galenic model. His anatomical teachings were based upon the dissection of human corpses, rather than the animal dissections that Galen had used as a guide. Vesalius' work emphasized the priority of dissection and what has come to be called the "anatomical" view of the body, seeing human internal functioning as an essentially corporeal structure filled with organs arranged in three-dimensional space. This was in stark contrast to many of the anatomical models used previously.

Further groundbreaking work was carried out by William Harvey, who published De Motu Cordis in 1628. Harvey made a detailed analysis of the overall structure of the heart, going on to an analysis of the arteries, showing how their pulsation depends upon the contraction of the left ventricle, while the contraction of the right ventricle propels its charge of blood into the pulmonary artery. He noticed that the two ventricles move together almost simultaneously and not independently like had been thought previously by his predecessors. Harvey also estimated the capacity of the heart, how much blood is expelled through each pump of the heart, and the number of times the heart beats in a half an hour. From these estimations, he went on to prove how the blood circulated in a circle.

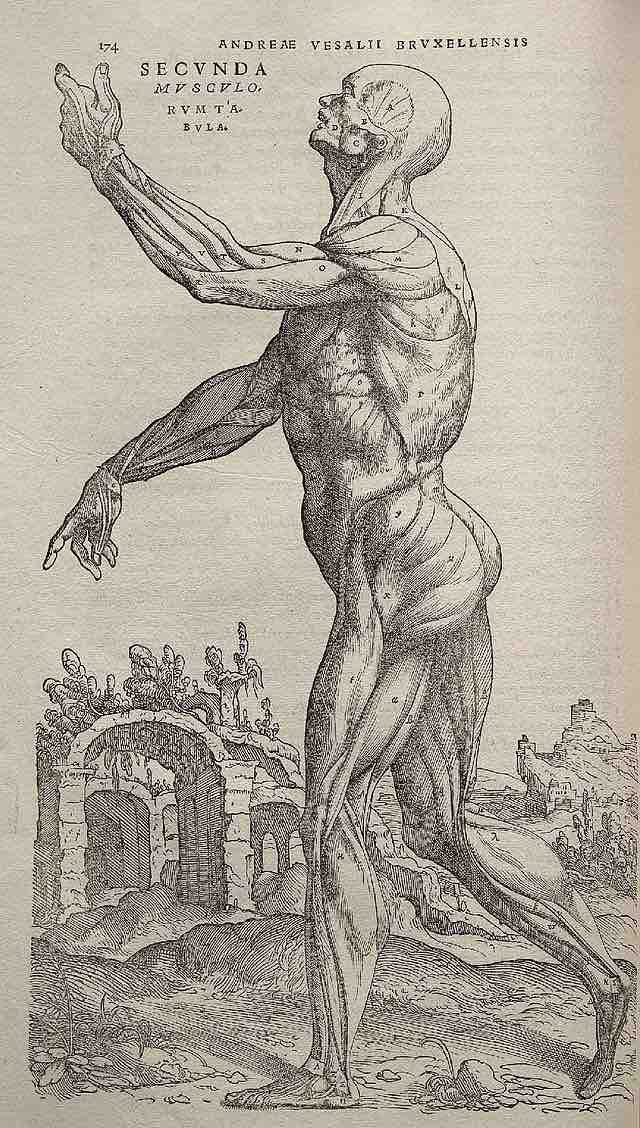

Andreas Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica, 1543, p. 174.

In 1543, Vesalius asked Johannes Oporinus to publish the seven-volume De humani corporis fabrica (On the fabric of the human body), a groundbreaking work of human anatomy. It emphasized the priority of dissection and what has come to be called the "anatomical view" of the human body.

OTHER MEDICAL ADVANCES

Various other advances in medical understanding and practice were made. French surgeon Ambroise Paré (c.1510–1590) is considered one of the fathers of surgery and modern forensic pathology and a pioneer in surgical techniques and battlefield medicine, especially in the treatment of wounds. He was also an anatomist and invented several surgical instruments and was part of the Parisian Barber Surgeon guild. Paré was also an important figure in the progress of obstetrics in the middle of the 16th century.

Herman Boerhaave (1668–1738), a Dutch botanist, chemist, Christian humanist and physician of European fame, is regarded as the founder of clinical teaching and of the modern academic hospital. He is sometimes referred to as "the father of physiology," along with the Venetian physician Santorio Santorio (1561–1636), who introduced the quantitative approach into medicine, and with his pupil Albrecht von Haller (1708–1777). He is best known for demonstrating the relation of symptoms to lesions and, in addition, he was the first to isolate the chemical urea from urine. He was the first physician that put thermometer measurements to clinical practice.

Bacteria and protists were first observed with a microscope by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in 1676, initiating the scientific field of microbiology.

French physician Pierre Fauchard started dentistry science as we know it today, and he has been named "the father of modern dentistry." He is widely known for writing the first complete scientific description of dentistry, Le Chirurgien Dentiste ("The Surgeon Dentist"), published in 1728. The book described basic oral anatomy and function, signs and symptoms of oral pathology, operative methods for removing decay and restoring teeth, periodontal disease (pyorrhea), orthodontics, replacement of missing teeth, and tooth transplantation.

Andreas Vesalius, De corporis humani fabrica libri septem, illustration attributed to Jan van Calcar (circa 1499–1546/1550).

The front cover illustration of De Humani Corporis Fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body, 1543), showing a public dissection being carried out by Vesalius himself. The book advanced the modern study of human anatomy.