Overview

Humanism, also known as Renaissance humanism, was an intellectual movement embraced by scholars, writers, and civic leaders in 14th and early 15th century Italy. The movement developed in response to the medieval scholastic conventions in education at the time, which emphasized practical, pre-professional, and scientific studies engaged in solely for job preparation, and typically by men alone. Humanists reacted against this utilitarian approach, seeking to create a citizenry who were able to speak and write with eloquence and thus able to engage the civic life of their communities. This was to be accomplished through the study of the "studia humanitatis," known today as the humanities: grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy. Humanism introduced a program to revive the cultural—and particularly the literary—legacy and moral philosophy of classical antiquity. The movement was largely founded on the ideals of Italian scholar and poet Francesco Petrarca, which were often centered around humanity's potential for achievement.

While humanism initially began as a predominantly literary movement, its influence quickly pervaded the general culture of the time, re-introducing classical Greek and Roman art forms and contributing to the development of the Renaissance. Humanists considered the ancient world to be the pinnacle of human achievement and thought its accomplishments should serve as the model for contemporary Europe. There were important centres of humanism in Florence, Naples, Rome, Venice, Genoa, Mantua, Ferrara, and Urbino.

Humanism was an optimistic philosophy that saw man as a rational and sentient being, with the ability to decide and think for himself. It saw man as inherently good by nature, which was in tension with the Christian view of man as the original sinner needing redemption. It provoked fresh insight into the nature of reality, questioning beyond God and spirituality, and provided knowledge about history beyond Christian history.

Humanist Art

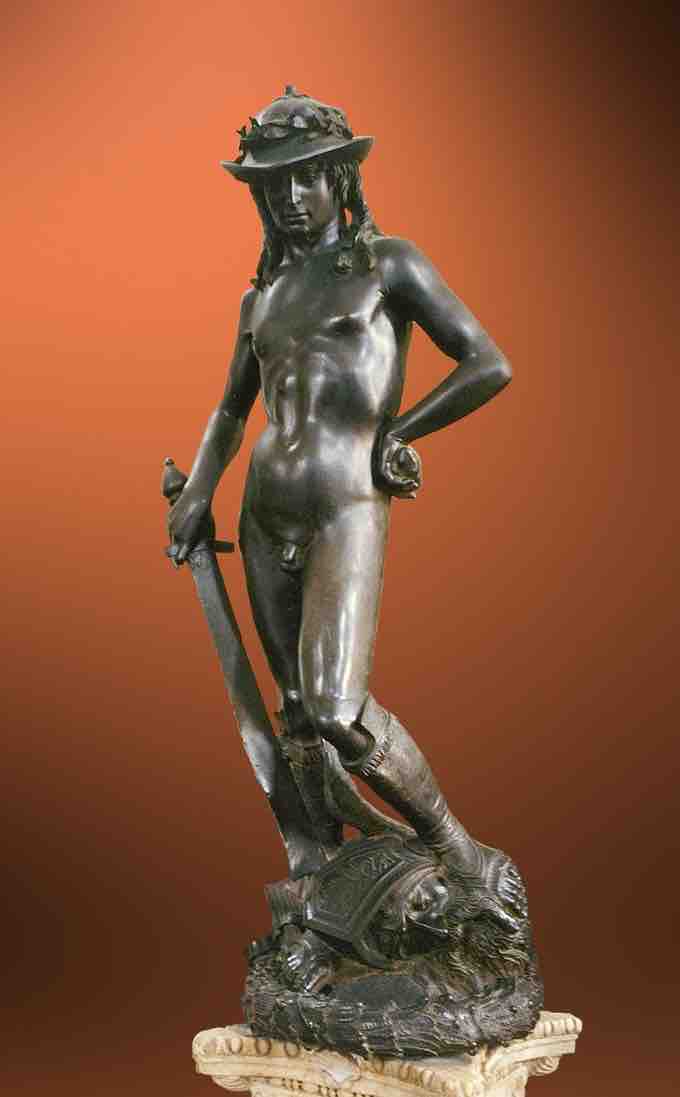

Renaissance humanists saw no conflict between their study of the Ancients and Christianity. The lack of perceived conflict allowed Early Renaissance artists to combine classical forms, classical themes, and Christian theology freely. Early Renaissance sculpture is a great way to explore the emerging Renaissance style. The leading artists of this medium were Donatello, Filippo Brunelleschi, and Lorenzo Ghiberti. Donatello became renowned as the greatest sculptor of the Early Renaissance, known especially for his classical, and unusually erotic, statue of David, which became one of the icons of the Florentine republic.

Donatello's David

Donatello's David is regarded as an iconic humanist work of art.

Humanism affected the artistic community and how artists were perceived. While medieval society viewed artists as servants and craftspeople, Renaissance artists were trained intellectuals, and their art reflected this newfound point of view. Patronage of the arts became an important activity and commissions included secular subject matter as well as religious. Important patrons, such as Cosimo de Medici, emerged and contributed largely to the expanding artistic production of the time.

In painting, the treatment of the elements of perspective and light became of particular concern. Paolo Uccello, for example, who is best known for "The Battle of San Romano," was obsessed by his interest in perspective and would stay up all night in his study trying to grasp the exact vanishing point. He used perspective in order to create a feeling of depth in his paintings. In addition, the use of oil paint had its beginnings in the early part of the 16th century and its use continued to be explored extensively throughout the High Renaissance.

"The Battle of San Romano" by Paolo Uccello

Italian humanist paintings were largely concerned with the depiction of perspective and light.

Origins

Some of the first humanists were great collectors of antique manuscripts, including Petrarch, Giovanni Boccaccio, Coluccio Salutati, and Poggio Bracciolini. Of the three, Petrarch was dubbed the "Father of Humanism" because of his devotion to Greek and Roman scrolls. Many worked for the organized Church and were in holy orders (like Petrarch), while others were lawyers and chancellors of Italian cities (such as Petrarch's disciple Salutati, the Chancellor of Florence) and thus had access to book copying workshops.

In Italy, the humanist educational program won rapid acceptance and, by the mid-15th century, many of the upper classes had received humanist educations, possibly in addition to traditional scholastic ones. Some of the highest officials of the Church were humanists with the resources to amass important libraries. Such was Cardinal Basilios Bessarion, a convert to the Latin Church from Greek Orthodoxy, who was considered for the papacy and was one of the most learned scholars of his time.

Following the Crusader sacking of Constantinople and the end of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, the migration of Byzantine Greek scholars and émigrés, who had greater familiarity with ancient languages and works, furthered the revival of Greek and Roman literature and science.