Egyptians were well known for their stelae, the earliest of which date back to the mid- to late third millennium BCE. Stelae are stone slabs that served many purposes, from funerary, to marking territory, to publishing decrees. Images and text were intimately interwoven and inscribed, carved in relief, or painted on the stelae. While most stelae were taller than they were wide, the slab stelae took a horizontal dimension and was used by a small list of ancient Egyptian dignitaries or their wives. The huge number of stelae surviving from ancient Egypt constitute one of the largest and most significant sources of information on those civilizations.

Funerary stelae were generally built in honor of the deceased and decorated with their names and titles. While some funerary stelae were in the form of slab stelae, this funerary stelae of a bowman named Semin (c. 2120-2051 BCE) appears to have been a traditional vertical stelae.

Funerary stelae of the bowman Semin

Funerary stelae were usually inscribed with the name and title of the deceased, along with images or hieroglyphs.

Slab stelae, when used for funerary purposes, were commonly commissioned by dignitaries and their wives. They also served as doorway lintels as early as the third millennium BCE, most famously decorating the home of Old Kingdom architect Hemon.

Stelae also were used to publish laws and decrees, to record a ruler's exploits and honors, mark sacred territories or mortgaged properties, or to commemorate military victories. Much of what we know of the kingdoms and administrations of Egyptian kings are from the public and private stelae that recorded bureaucratic titles and other administrative information. One example of such stelae is the Annals of Amenemhat II, an important historical document for the reign of Amenemhat II (r. 1929–1895 BCE) and also for the history of Ancient Egypt and understanding kingship in general.

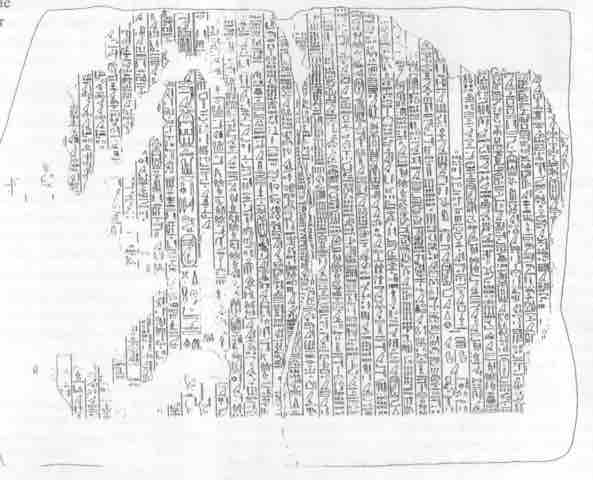

Annals of Amenemhat II

This drawing represents one of the larger fragments of this stelae.

Many stelae were used as territorial markers to delineate land ownership. The most famous of these would be used at Amarna during the New Kingdom under Akhenaten. For much of Egyptian history, including the Middle Kingdom, obelisks erected in pairs were used to mark the entrances of temples. The earliest temple obelisk still in its original position is the red granite Obelisk of Senusret I (Twelfth Dynasty) at Al-Matariyyah in modern Heliopolis. The obelisk was the symbol and perceived place of existence of the sun god Ra.

Obelisk of Senusret I

This obelisk is one half of a pair that originally marked the entrance to the temple of the sun god Ra.