The Book of the Dead is the modern name of an ancient Egyptian funerary text, used from the beginning of the New Kingdom (around 1550 BCE) to around 50 BCE. The original Egyptian name is translated as "Book of Coming Forth by Day," or "Book of Emerging Forth into the Light." According to ancient Egyptian beliefs, it was the ba (the free-ranging spirit aspect of the deceased) that went "forth by day" into the underworld and afterlife, while the ka (life force) remained in the tomb.

Despite the word "book" in the common title, the Book of the Dead was actually printed on scrolls, as opposed to bound texts. The text, placed in the coffin or burial chamber of the deceased, consisted of magic spells intended to assist a deceased person's journey through the Duat, or underworld, and into the afterlife. At present, some 192 spells are known, though no single manuscript contains all of them. The spells served a range of purposes, such as giving the deceased mystical knowledge in the afterlife, guiding them past obstacles in the underworld, or protecting them from various hostile forces. In total, the spells in the Book of the Dead provide vital information regarding ancient Egyptian beliefs on death, interment, and the afterlife.

Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts

The Book of the Dead was part of a tradition of funerary texts which includes the earlier Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom and the Coffin Texts of the Middle Kingdom. However, it differed from its predecessors in many ways. For instance, Pyramid Texts were written in an unusual hieroglyphic style, were exclusive to those of royal privilege, and saw the afterlife as being in the sky. The Coffin Texts used a newer version of the language, included illustrations for the first time, and were available to wealthy private individuals. Both were painted onto walls or objects in the funerary chamber. The Book of the Dead, in contrast, was painted on expensive papyrus, written in cursive hieroglyph, and saw the afterlife as being part of the underworld. The earliest examples developed towards the beginning of the Second Intermediate Period, around 1700 BCE, and included new spells among older texts. By the Seventeenth Dynasty, the spells were typically inscribed on linen shrouds wrapped around the dead, though occasionally they are found written on coffins or on papyrus.

The Book of the Dead

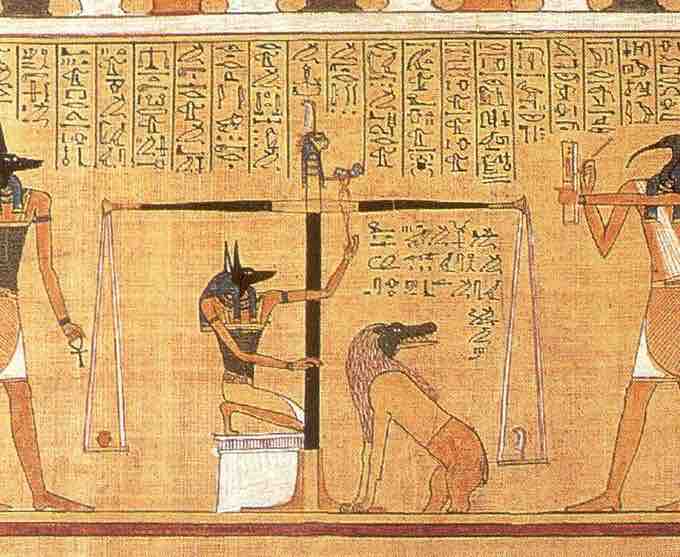

The New Kingdom saw the Book of the Dead develop and spread further. The famous "Spell 125," the Weighing of the Heart, is first known from the reign of Hatshepsut and Tuthmose III (c.1475 BCE). In "Spell 125," the heart of the deceased must be weighed against the Feather of Truth before the deceased can pass into the afterlife. The jackal-headed god Anubis weighed the heart, while the ibis-headed god Thoth recorded the results. A heavy heart indicated sin and resulted in the deceased being devoured by a crocodile-like creature named Ammit. On the other hand, a lightweight heart equal with the weight of the feather allowed the deceased to enter the afterlife and enjoy an eternity that, although plentiful, required manual labor. For this reason, the Book of the Dead included spells for statuettes called shebti (later ushebti) to perform in the deceased's place.

From the fourteenth century BCE onward, the Book of the Dead was typically written on a papyrus scroll and the text was illustrated with elaborate and lavish vignettes. Later in the Third Intermediate Period, the Book of the Dead started to appear in hieratic script as well as in the traditional hieroglyphics. The last use of the Book of the Dead was in the first century BCE, though some artistic motifs drawn from it were still in use in Roman times.

The Weighing of the Heart

In Spell 125, Anubis weighs the heart of Hunefer. This spell is first known from the reign of Hatshepsut and Tuthmose III, c. 1475 BC.

There was no single Book of the Dead, and works tended to vary widely. Some people seem to have commissioned their own copies, perhaps choosing the spells they thought were most vital in their own progression to the afterlife. Later in the Twenty-Fifth and Twenty-Sixth Dynasties, however, the Book was revised and standardized, with spells consistently ordered and numbered for the first time.

Books were commissioned by people in preparation for their own funeral, or by the relatives of someone recently deceased. They were written by scribes, and sometimes the work of several different scribes was literally pasted together. Composed of joined sheets of papyrus, the dimensions of a Book of the Dead could vary from one to 40 meters. Books were often prefabricated in funerary workshops, with space left for when the name of the deceased would be written in later.

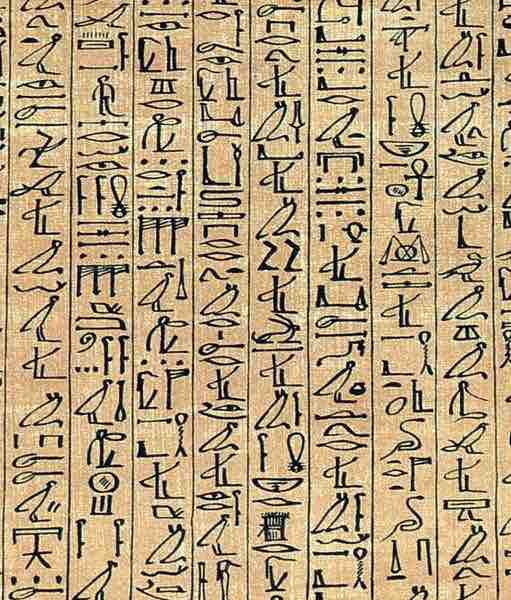

The text of a New Kingdom Book of the Dead was typically written in cursive hieroglyphs, most often from left to right, but also sometimes from right to left. The hieroglyphs were in columns separated by black lines, and illustrations were put in frames above, below, or between the columns of text. The text was written in both black and red ink from either carbon or ochre, respectively. The style and nature of the vignettes used to illustrate a Book of the Dead varies widely: some contain lavish color illustrations, even making use of gold leaf, while others contain only line drawings or a simple illustration at the opening.

Cursive hieroglyphs from the Papyrus of Ani

During the New Kingdom, the Book of the Dead was typically written in cursive hieroglyphs.