Mycenaean culture can be summarized by its architecture, whose remains demonstrate the Mycenaeans' war-like culture and the dominance of citadel sites ruled by a single ruler. The Mycenaeans populated Greece and built citadels on high, rocky outcroppings that provided natural fortification and overlooked plains used for farming and raising livestock. The citadels vary from city to city but each share common attributes including building techniques and architectural features.

Building Techniques

The walls of Mycenaean citadel sites were often built with ashlar and massive stone blocks. The blocks were considered too large to be moved by humans and were believed by ancient Greeks to have been erected by Cyclopes, or one-eyed giants. Due to this ancient belief the use of large, roughly cut, ashlar blocks in building is referred to as Cyclopean masonry. The thick Cyclopean walls reflect a need for protection and self-defense since these walls often encircled the citadel site and the acropolis on which the site was located.

The Mycenaeans also relied on new techniques of building to create supportive archways and vaults. A typical post and lintel structure is not strong enough to support the heavy structures built above it. Therefore, a corbeled (or corbel) arch is employed over doorways to relieve the weight on the lintel. The corbel arch is constructed by offsetting successive courses of stone (or brick) at the springline of the walls so that they project towards the archway's center from each supporting side, until the courses meet at the apex of the archway (often, the last gap is bridged with a flat stone). The corbel arch was often used by the Mycenaeans in conjunction with a relieving triangle, which was a triangular block of stone that fit into the recess of the corbeled arch and helped to redistribute weight from the lintel to the supporting walls.

Corbeled vault, Tiryns.

Citadel sites

Mycenaean citadel sites were centered around the megaron, a reception area for the king. The megaron was a rectangular hall, fronted by an open, two-columned porch. It contained a more or less central open hearth, which was vented though an oculus in the roof above it and surrounded by four columns. The architectural plan of the megaron became the basic shape of Greek temples, demonstrating the cultural shift as the gods of ancient Greece took the place of the Mycenaean rulers.

Citadel sites were protected from invasion through natural and man-made fortification. In addition to thick walls, the sites were protected by controlled access. Entrance to the site was through one or two large gates, and the pathway into the main part of the citadel was often controlled by more gates or narrow passageways. Since citadels had to protect the area's people in times of warfare, the sites were equipped for sieges. Deep water wells, storage rooms, and open space for livestock and additional citizens allowed a city to access basic needs while being protected during times of war.

Mycenae

The citadel site of Mycenae was the center of Mycenaean culture. It overlooks the Argos plain on the Peloponnesian peninsula, and according to Greek mythology was the home to King Agamemnon. The site's megaron sits on the highest part of the acropolis and is reached through a large staircase. Inside the walls are various rooms for administration and storage along with palace quarters, living spaces, and temples. A large grave site, known as Grave Circle A, is also built within the walls. The main approach to the citadel is through the Lion Gate, a cyclopean walled entrance way. The gate is 20 feet wide, which was large enough for citizens and wagons to pass through, but its size and the walls on either side that create a tunneling effect. This would have made it difficult for an invading army to penetrate. The gate is famous for its use of the relieving arch, a corbeled arch that leaves an opening and lightens the weight carried by the lintel. The Lion Gate received its name from its decorated relieving triangle of lions one either side of a single column. This composition of lions or another feline animal flanking a single object is known as a heraldic composition. The lions represent cultural influences from the Ancient Near East. Their heads are turned to face outwards and confront those entered the gate.

Lion Gate. Limestone. C. 1300-1250 BCE. Mycenae, Greece.

The Lion Gate is famous for its use of the relieving arch, a corbeled arch that leaves an opening and lightens the weight carried by the lintel.

Mycenae is also home to a subterranean beehive shaped tomb (also known as a tholos tomb) that was located outside the citadel walls. The tomb today is known as the Treasury of Atreus, due to the wealth of grave goods found there. This tomb and others like it are demonstrations of corbeled vaulting that covers an expansive open space. The vault is 44 feet high and 48 feet in diameter. The tombs are entered through a narrow passageway known as a dromos and a post-and-lintel doorway topped by a relieving triangle.

Treasury of Atreus, Mycenae, Greece, c. 1300-1250 BCE.

The Treasure of Atreus and others tombs like it are demonstrations of corbeled vaulting that covers an expansive open space.

Tiyrns

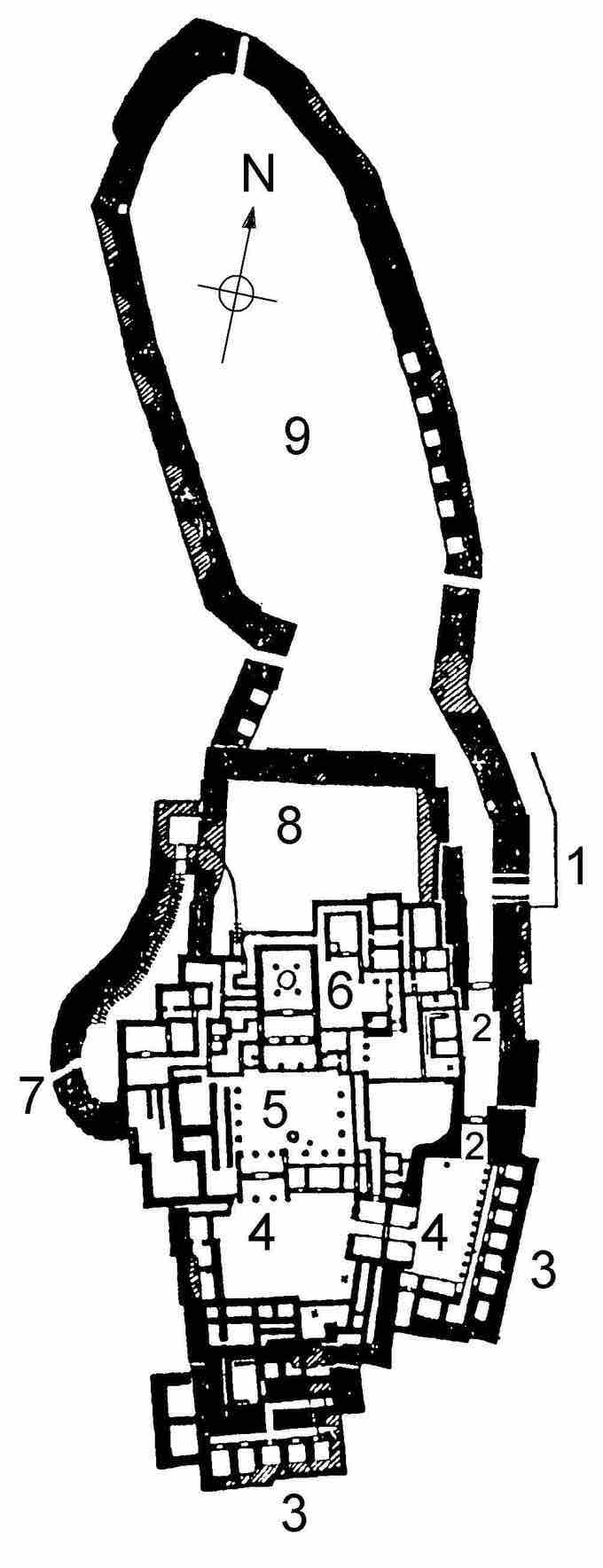

The citadel site of Tiryns, another example of Mycenaean fortification, was a hill fort with occupation ranging back 7000 years. It reached its height between 1400 and 1200 BCE, when it was one of the most important centers of the Mycenaean world. Its most notable features were its palace, its Cyclopean tunnels, its walls, and its tightly controlled access to the megaron and main rooms of the citadel.

Just a few gates provide access to the hill but only one path leads to the main site. This path is narrow and protected by a series of gates that could be opened and closed to trap invaders. The central megaron is easy to locate, and it is surrounded by various palatial and administrative rooms. The megaron is accessed through a courtyard that is decorated on three sides with a colonnade.

Ground plan of the citadel of Tiryns. c. 1400-1200 BCE. Tiryns, Greece.

The citadel site of Tiyrns is known for its Cyclopean vaulted tunnels that run next to its walls and its tightly controlled access to the megaron and the main rooms of the citadel.

The famous megaron has a large reception hall, the main room of which had a throne placed against the right wall and a central hearth bordered by four wooden columns that served as supports for the roof. It was laid out around a circular hearth surrounded by four columns. Although individual citadel sites varied to a degree, their overall uniformity allows us to compare design elements easily. For example, the hearth of the megaron at the citadel of Pylos provides an idea of how its counterpart at Tiryns appears.

Megaron hearth at the citadel of Pylos.

Due to the uniformity of citadel plans throughout the Mycenaean civilization, we can get an idea of how the hearth of the megaron at Tiryns looked by comparing it to its counterpart at Pylos. The holes at the corners of the surrounding square once held wooden columns.