Carolingian-era metalworkers primarily worked with gold, gems, ivory, and other precious materials. For instance, luxury Carolingian manuscripts were given treasure bindings and elaborately ornate covers in precious metals set with jewels around central carved ivory panels. Metalwork subjects were often narrative religious scenes in vertical sections, largely derived from Late Antique paintings and carvings, as were those with more hieratic images derived from consular diptychs and other imperial art, such as the front and back covers of the Lorsch Gospels.

Important Carolingian examples of metalwork came out of Charles the Bald's "Palace School" workshop, and include the cover of the Lindau Gospels, the cover of the Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram , and the Arnulf Ciborium. All three of these works feature fine relief figures in repoussé gold. Another work associated with the Palace School is the frame of an antique serpentine dish, now located in the Louvre.

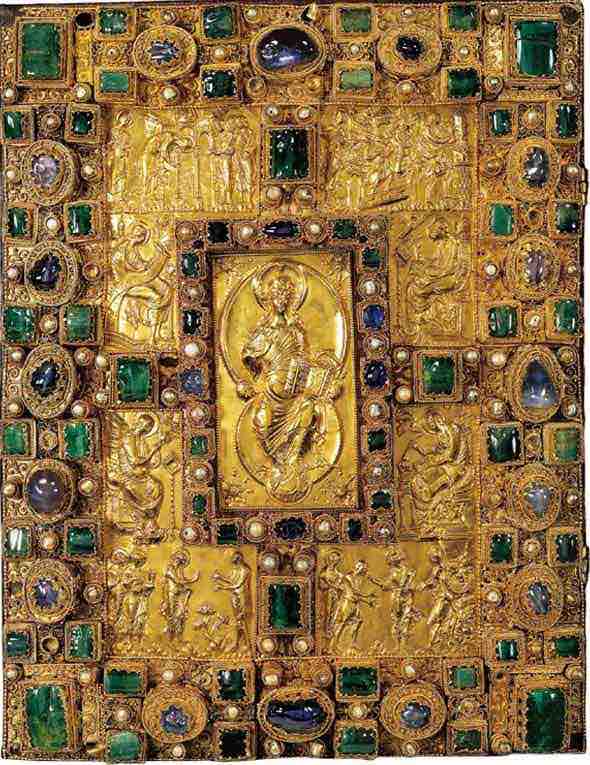

Cover of the Codex Aureus

Gold and gem-encrusted cover of the Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram, 870.Produced by the Carolingian Palace School.

Under Charlemagne, there was a revival of large-scale bronze casting in imitation of Roman designs, although metalwork in gold continued to develop. For example, the Aachen chapel's figure of Christ in gold (now lost) was the first known work of this type that was later to become a crucial inspiring feature of northern European medieval art. Another one of the finest examples of Carolingian metalwork is the Golden Altar (824–859), also known as the Paliotto, in the Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio in Milan (since damaged by WWII bombings). The altar's four sides are decorated with images in gold and silver repoussé, framed by borders of filigree, precious stones, and enamel.