The Chora Church's full name is the Church of the Holy Savior in Chora. The church was first built in Constantinople the early fifth century. Its name references its location outside the city's fourth-century walls. Even when the walls were expanded in the early fifth century by Theodosius II, the church maintained its name. Inside the church is a set of frescos and mosaics that survived the church's conversion into a mosque in the sixteenth century and the plastering over of the Christian imagery. In 1948 the church became a museum after undergoing extensive restoration to uncover and restore its fourteenth-century decoration. It is now known as the Kariye Museum or Kariye Camii.

Architecture

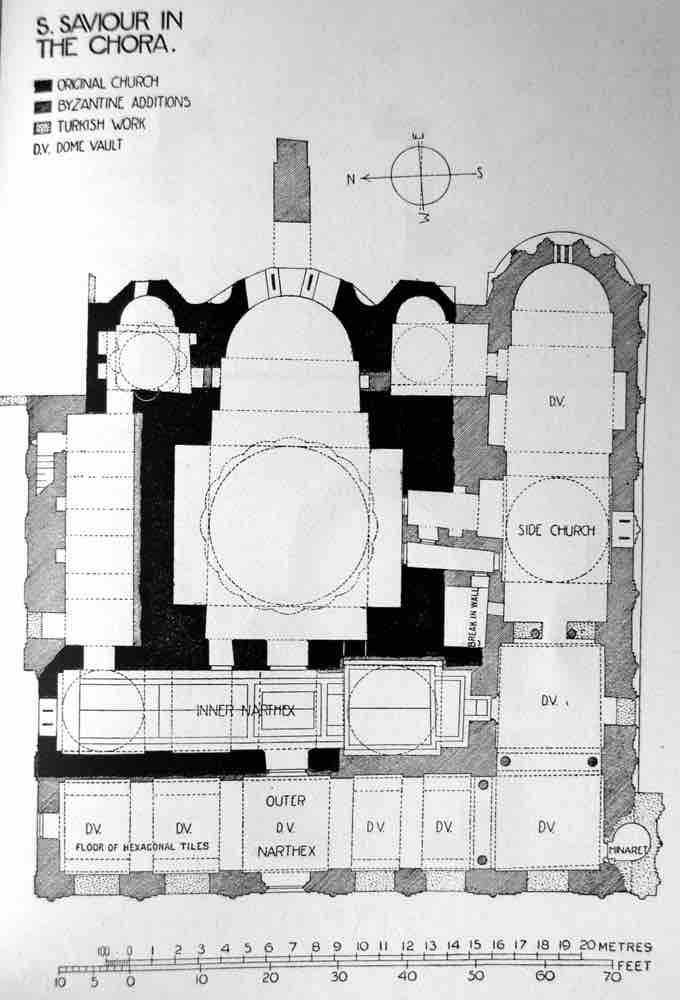

The Chora Church that stands today is the result of its third stage of construction. This building and the interior decoration were completed between 1315 and 1321 under the Byzantine statesman Theodore Metochites. Metochites's additions and reconstruction in the fourteenth century enlarged the ground plan from the original small, symmetrical church into a large, asymmetrical square that consists of three main areas: an inner and outer narthex or entrance hall, the naos or main chapel, and the side chapel, known as the parecclesion. The parecclesion serves as a mortuary chapel and held eight tombs that were added after the area was initially decorated. There are six domes in the church, three over the naos (one over the main space and two over smaller chapels), two in the inner narthex, and one in the side chapel. The domes are pumpkin-shaped, with concave bands radiating from the center, and are richly decorated with frescos and mosaics that depicted images of Christ and the Virgin at the center with angels or ancestors surrounding them in the bands.

Ground plan of the Chora Church.

Ground plan of the Chora Church.

Mosaics

Mosaics extensively decorate the narthices of the Chora Church. The artists first decorated the church in the naos and then completed the work in the inner and outer narthices which results in differences in the mosaics' execution as the style progressed to show more liveliness and subtlety. The surviving mosaics in the naos depict the Virgin and Child and the Dormition of the Virgin, a koimesis scene depicting the Virgin after death before she ascends to Heaven. This scene, located above the west door, depicts the Virgin in blue lying on a sarcophagus draped in purple and gold. Christ, in gold, stands behind the Virgin surrounded by a mandorla and holds an infant, representing the Virgin's soul. The figures in the scene all have a certain weightiness that helps to ground them, adding an element of naturalism.

Koimesis Mosaic.

1310-1320. Naos, Chora Church, Constantinople (Istanbul), Turkey.

The mosaics found in the narthices of the Chora Church also depict scenes of the lives of the Virgin and Christ, while other scenes depict Old Testament stories that prefigure the Salavation. In the outer narthex, above the doorway to the inner narthex is a mosaic depicting Christ as the Pantocrator, the ruler or judge of all, in the center of a dome. The mosaic depicts a stern-faced Christ against a gold backdrop holding the gospels in one hand while gesturing with the other. An inscription in the mosaic reads, "Jesus Christ, Land of the Living."

South Dome of the Inner Narthex.

South dome of the inner narthex depicting Christ Pantocrator surrounded by ancestors. 1310-1320. Inner Narthex, Chora Church, Constantinople (Istanbul), Turkey.

In another important scene above the entrance to the naos, Christ Enthroned is depicted receiving the donor of the church. The scene follows the Byzantine convention of depicting an architectural donation with an image of Christ in the center and the donor kneeling beside him, holding a model of his donation. Here, Christ sits on a throne in a position similar to the Pantocrater, holding a book of gospels with his other hand gesturing. The donor Theodore Metochites, wearing the clothing of his office, kneels on Christ's right. He offers Christ a representation of the Chora Church in his hands. An inscription gives his titles.

Dedication Mosaic.

1310-1320. Outer Narthex, Chora Church, Constantinople (Istanbul), Turkey.

Frescos

The walls and ceilings of the parecclesion are decorated with scenes from the life of Christ and the Virgin and themes of salvation befitting for a mortuary chapel. Like the mosaics, the scenes are painted in the upper levels of the building. The lower levels are reserved for painted images of saints and prophets and a decorative dado that mimics marble revetment. The entirety of the parecclesion is covered in fresco scenes and painted images, creating an overwhelming sense of splendor and glory that ultimately brings the viewer to the final scenes of salvation and judgment.

Virgin and Child with Angels.

Dome depicting the Virgin and Child with Angels. Fresco. 1310-1320. Parecclesion, Chora Church, Constantinople (Istanbul), Turkey.

The most important of these frescos is the Anastasis, a representation of the Last Judgment, in the apse of the eastern bay. This image depicts Christ in Hell, saving the souls of the Old Testament. Christ stands in the center grasping the wrists of Adam and Eve, whom he raises from their sarcophagi. Saints, prophets, martyrs and other righteous souls, including John the Baptist, King David, and King Solomon, from the Old Testament stand on either side of Christ. Christ, standing over a bound Satan, wears a white robe and is framed by a white and light blue mandorla.

Anastasis

Fresco. 1310-1320. Parecclesion, Chora Church, Constantinople (Istanbul), Turkey.

The image is the culmination of the parecclesion's fresco cycle and one of the most impressive Late Byzantine paintings. Christ stands in an active, chiastic position. His arms reach out to Adam and Eve and his feet are positioned on uneven ground, providing the sensation of imbalance as he retrieves righteous souls. The figures themselves are rendered in a softer, subtler mode. The harsh jagged drapery has softened slightly with fluid and delineated folds. The expression of Christ and the others are dignified and stern. The Old Testament figures on either side gesture towards the scene, signaling the future of the faithful, as they wait for Christ to bring them into Heaven.

Changing Representations of Christ

The depictions of Christ in the Chora Church differ greatly from those of the third and fourth centuries. Recalling Early Christian art, Christ often appears clean shaven and youthful, sometimes cast as the Good Shepherd who tends and rescues his flock from danger. At a time when Christianity was illegal, Christians would have found such imagery of a protector reassuring.

By the fourteenth century when Theodore Metochites funded the interior decoration, Christianity was no longer a fledgling faith; it was a state religion in which even the emperor recognized Christ as the ultimate authority. The images of Christ in the frescoes and mosaics of the Chora Church depict an authoritative bearded man who occupies the role of both savior and judge. As an archetypal symbol of authority and wisdom through the ages, the beard would have been a logical choice for the face of the most supreme leader.