Painting during the Middle Byzantine period began to progress and change stylistically. Artists approached common scenes with an ingenuity based on a mix of naturalism, especially in the conveyance of emotional reaction, and schematics, especially in specific rendering of the body. This can be seen in the fresco of the Lamentation found in the Church of Saint Pantaleimon in the city of Nerezi, Macedonia, an illumination of the Death of St. Onesimus, and an icon of the Virgin and Child.

Lamentation from Saint Pantaleimon, Nerezi, Macedonia

The Lamentation of Christ is an iconic scene that depicts the Virgin Mary hold and mourning her dead son, just after Christ has been removed from the cross. She wraps an arm around his shoulders and presses her face against his. St. John grasps Christ's right hand while Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus kneel at Christ's feet. A fifth follower enters the scene with arms outstretched from the right and group of angels fly above the scene in the deep blue sky.

The Macedonian painters created a scene filled with emotional tension unprecedented in Byzantine art. The figures faces are neither solemn nor formal but instead are emotionally charged with grief and sorrow. Mary's face especially denotes the emotion and pain that a mother feels when grieving a lost child. The figures are also bent over Christ's body, which further emphasizes the emotions in the scene—no longer stiff or static, these figures feel and cause the viewer to be filled with emotion.

Lamentation of Christ

Detail. Wall painting. 1164. Church of Saint Pantaleimon, Nerezi, Macedonia.

Despite these elements of naturalism, there are some elements of Byzantine style in the fresco. For one, the figures' clothing is still schematically rendered, even though most of the figures appear to have bodies and mass under their garments. For another, the seminude body of Christ is rendered in a style similar to the drapery. The muscles are defined through schematic lines that denote parts of his body, such as his knees and abdominal muscles. Another oddity is that Christ's body is not on the ground but instead hovers non-naturalisticaly off the ground. This is hardly noticed at first, since the placement of his torso and feet make sense in their individual context, but as whole it requires Christ's body to float, instead of lay naturally on the ground.

The Death of St. Onesimus

A similar mixture of naturalism and stylization is evident in a painting depicting the martyrdom of Saint Onesimus (c. 985 CE). The image is part of the Menologion of Basil II, an illuminated manuscript compiled circa 1000 CE as a church calendar. The Epistle to Philemon, written by Paul the Apostle to the slave-master Philemon, concerns a runaway slave called Onesimus. This slave found his way to the site of Paul's imprisonment to escape punishment for a theft of which he was accused. After hearing the Gospel from Paul, Onesimus converted to Christianity. Paul, having earlier converted Philemon to Christianity, sought to reconcile the two by writing the letter to Philemon which today exists in the New Testament. During the reign of Roman emperor Domitian and the persecution of Trajan, Onesimus was imprisoned in Rome and might have been martyred by stoning, although some sources claim that he was beheaded.

The Death of St. Onesimus

From the Monologion of Basil II. Painting produced c. 985 CE; book assembled c. 1000.

As in the Lamentation scene above, the Death of St. Onesimus combines the naturalistic and the schematic. The two mean who beat Onesimus to death convey a sense of dynamism as they bend at the waists and knees. The folds of their clothing and of Onesimus's loincloth follows the contours of their bodies as they assume their poses. Although the painting is damaged, Onesimus's furrowed brow, possibly suggesting anger or frustration, is still visible. Despite these realistic elements, the folds of the figures' clothing appears more linear than natural, defined by deep, noticeable lines. Like the figure of Christ in the Lamentation, Onesimus seems to hover over the landscape and rest the top half of his body on the leg of one of his attackers. Furthermore, the blood pours from his legs in a linear manner, appearing more like strings than liquid.

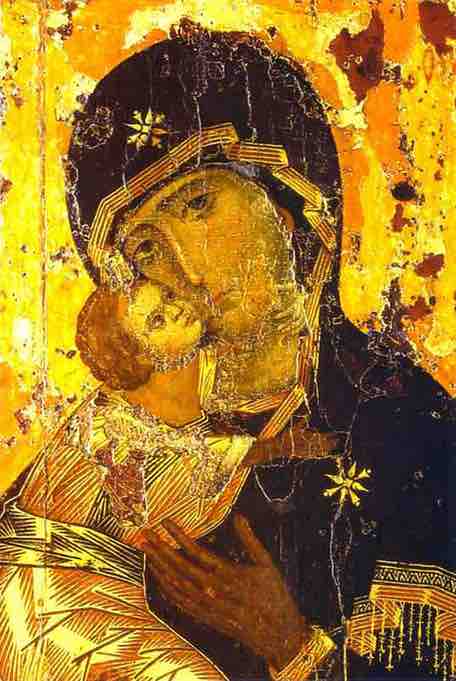

Theotokos of Vladimir

The Theotokos of Vladimir, an icon of the Virgin and Child, represents the new style of icons that were created in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. These icons depict emotion, compassion, and the growing trend in spirituality. The mother and child are depicted with serene faces in the Byzantine style. Mary's nose is long and narrow and her mouth small. She looks out and confronts the viewer with compassionate, knowing eyes that remind the viewer of Christ's future sacrifice. The Christ child is small, although his face is adult-like and he is drawn to his mother and embraces her. His drapery shines as if it was golden rays, and the Virgin is dressed in rich, dark fabric with gold embellishments. The compassion and humanity between the characters prefigures the emotional Late Byzantine style of the next two centuries. The image was given as a gift to the Grand Duke of Kiev in 1131 by the Greek Patriarch of Constantinople and is an important and protective icon of the Russian cities of Vladimir and Moscow and the country of Russia itself.

Theotokos of Vladimir

Theotokos of Vladimir. Tempera on wood. Late 11th to early 12th century. Vladimir, Russia.