The increasing mass production of paper, coupled with the invention of the printing press in 15th century Europe, opened the doors for the proliferation of printed books. Woodcut printing on textiles had been practiced in Europe for some time when paper became more affordable and readily available. Around 1450, small woodcut books called "block books" or "xylographica" came into prominence and were reproduced in large numbers. Block books were short books consisting of up to 50 leaves block-printed with woodcuts carved to include both text and imagery. These books were aimed at a general audience and were often popular titles, nearly always religious in nature, and sometimes reprinted into multiple editions. Germany and Northern Europe were important centers for the spread and development of printed works during the 15th and 16th centuries.

It is widely believed that block books existed as a cheaper alternative to the movable-type printed book, which was in use but still very expensive. Research has uncovered over 40 titles, with a much smaller number ranking among the most popular. The most popular texts were reprinted many times, often using new woodcuts copying the earlier versions. Block books were typically printed as folios, with two pages printed on one full sheet of paper, which was then folded once for binding. Several such leaves were then inserted inside another to form a gathering of leaves, one or more of which would be sewn together to form the complete book. Some block books, called "chiro-xylographic," were printed with only illustrations, and then the type was filled in by hand. Block books are considered incunabula (or "incunable"), a term referring to a book, pamphlet, or broadside printed before the year 1501 in Europe.

The most renowned block book is the Ars Moriendi, or The Art of Dying, from the Netherlands. It was reprinted in several editions with different illustrations. There was originally a "long version" and a later "short version" containing 11 woodcut pictures as instructive images that could be easily explained and memorized. It was written within the historical context of the effects of the macabre horrors of the Black Death 60 years earlier and consequent social upheavals of the 15th century. It was very popular, translated into most West European languages, and was the first in a Western literary tradition of guides to death and dying.

A Print from the Ars Moriendi

The Ars Moriendi is the most renowned block book.

The Biblia Pauperum, or Pauper's Bible, was also a popular series that had existed previously in the 14th century as illuminated manuscripts, hand-painted on vellum, before woodcuts took over. A Biblia Pauperum included visual depictions that related the Old Testament to the New Testament, often placing the illustrations in the center with very little additional text. When text did appear in the Biblia Pauperum, it was usually in the local vernacular language, rather than Latin. Each group of images is dedicated to one event from the Gospels, which is accompanied by two slightly smaller pictures of Old Testament events that prefigure the central one, according to belief of medieval theologians. Other notable Biblia paupera include the Gutenberg Bible of 1455, as well as the incunabula of 1486, printed and illustrated by Erhard Reuwich.

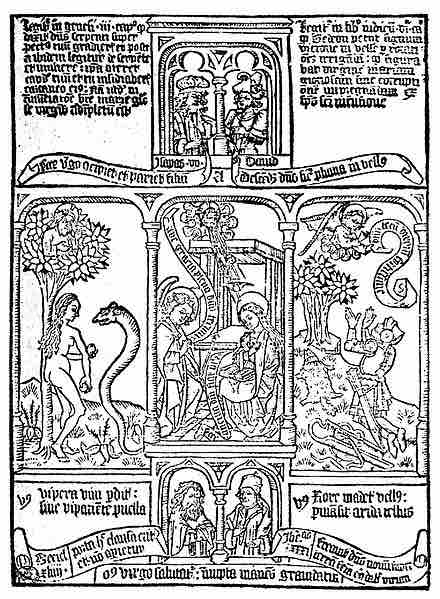

Woodblock Print from a Biblia Pauperum

Three episodes from the block book Biblia Pauperum illustrating typological correspondences between the Old and New Testaments: Eve and the serpent, the Annunciation, and Gideon's miracle.

Polychromatic block books were produced in addition to the monochromatic ones. Whereas most polychromatic prints required a separate printing surface for each color used, polychromatic block books were colored by hand. Pigments ranged from plant materials, such as ochre (red and yellow), to more chemically-derived ones, such as cobalt (blue). Various insect species were also used for a variety of red values. Since block books were less expensive than traditional illuminated manuscripts, artists colored the images exclusively in paints and inks, as opposed to gilding.

Polychromatic page from the Apocalypse, c. 1450–1500

Heavy areas of color and modeling, which obscure the outlines and contour lines, point to evidence of hand-coloring, as opposed to using a separate block for each color. The printed text is in Latin but handwritten German translation sheets were inserted between the block book pages.

Most of the earliest block books are believed to have been printed in the Netherlands, while the later ones are thought to be from Southern Germany. Specifically, Nuremberg, Ulm, Augsburg, and Schwaben were notable locations for the development of print media in the 15th and 16th centuries.