Chromalveolata

Current evidence suggests that species classified as chromalveolates are derived from a common ancestor that engulfed a photosynthetic red algal cell, which itself had already evolved chloroplasts from an endosymbiotic relationship with a photosynthetic prokaryote. Therefore, the ancestor of chromalveolates is believed to have resulted from a secondary endosymbiotic event. However, some chromalveolates appear to have lost red alga-derived plastid organelles or lack plastid genes altogether. Therefore, this supergroup should be considered a hypothesis-based working group that is subject to change and can be subdivided into alveolates and stramenopiles.

Alveolates

A large body of data supports that the alveolates are derived from a shared common ancestor. The alveolates are named for the presence of an alveolus, or membrane-enclosed sac, beneath the cell membrane. The exact function of the alveolus is unknown, but it may be involved in osmoregulation. The alveolates are further categorized into the dinoflagellates, the apicomplexans, and the ciliates.

Dinoflagellates

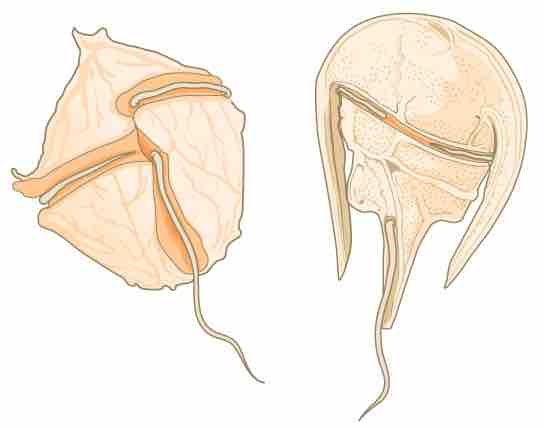

Dinoflagellates exhibit extensive morphological diversity and can be photosynthetic, heterotrophic, or mixotrophic. Many dinoflagellates are encased in interlocking plates of cellulose with two perpendicular flagella that fit into the grooves between the cellulose plates . One flagellum extends longitudinally and a second encircles the dinoflagellate. Together, the flagella contribute to the characteristic spinning motion of dinoflagellates. These protists exist in freshwater and marine habitats; they are a component of plankton.

Dinoflagellates

The dinoflagellates exhibit great diversity in shape. Many are encased in cellulose armor and have two flagella that fit in grooves between the plates. Movement of these two perpendicular flagella causes a spinning motion.

Some dinoflagellates generate light, called bioluminescence, when they are jarred or stressed. Large numbers of marine dinoflagellates (billions or trillions of cells per wave) can emit light and cause an entire breaking wave to twinkle or take on a brilliant blue color . For approximately 20 species of marine dinoflagellates, population explosions (called blooms) during the summer months can tint the ocean with a muddy red color. This phenomenon is called a red tide and results from the abundant red pigments present in dinoflagellate plastids. In large quantities, these dinoflagellate species secrete an asphyxiating toxin that can kill fish, birds, and marine mammals. Red tides can be massively detrimental to commercial fisheries; humans who consume these protists may become poisoned.

Bioluminescence

Bioluminescence is emitted from dinoflagellates in a breaking wave, as seen from the New Jersey coast.

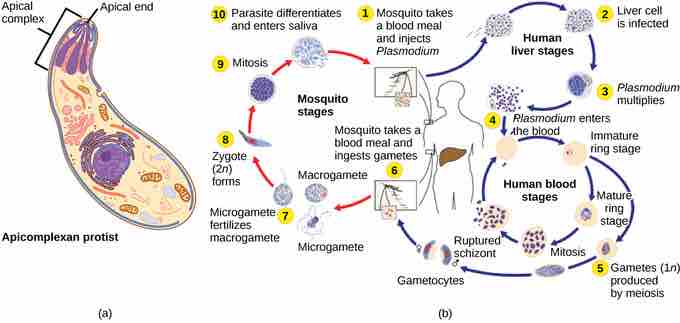

Apicomplexans

The apicomplexan protists are so named because their microtubules, fibrin, and vacuoles are asymmetrically distributed at one end of the cell in a structure called an apical complex . The apical complex is specialized for entry and infection of host cells. Indeed, all apicomplexans are parasitic. This group includes the genus Plasmodium, which causes malaria in humans. Apicomplexan life cycles are complex, involving multiple hosts and stages of sexual and asexual reproduction.

Parasitic apicomplexans

(a) Apicomplexans are parasitic protists. They have a characteristic apical complex that enables them to infect host cells. (b) Plasmodium, the causative agent of malaria, has a complex life cycle typical of apicomplexans.

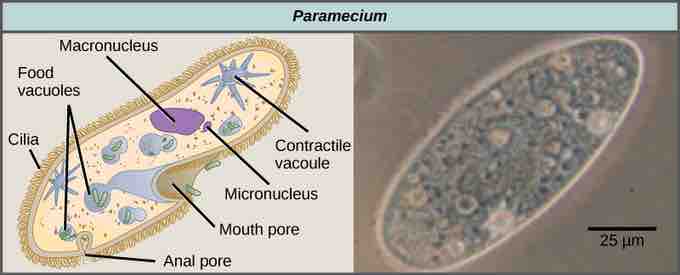

Ciliates

The ciliates, which include Paramecium and Tetrahymena, are a group of protists 10 to 3,000 micrometers in length that are covered in rows, tufts, or spirals of tiny cilia. By beating their cilia synchronously or in waves, ciliates can coordinate directed movements and ingest food particles. Certain ciliates have fused cilia-based structures that function like paddles, funnels, or fins. Ciliates also are surrounded by a pellicle, providing protection without compromising agility. The genus Paramecium includes protists that have organized their cilia into a plate-like primitive mouth called an oral groove, which is used to capture and digest bacteria . Food captured in the oral groove enters a food vacuole where it combines with digestive enzymes. Waste particles are expelled by an exocytic vesicle that fuses at a specific region on the cell membrane: the anal pore. In addition to a vacuole-based digestive system, Paramecium also uses contractile vacuoles: osmoregulatory vesicles that fill with water as it enters the cell by osmosis and then contract to squeeze water from the cell.

Paramecium

Paramecium has a primitive mouth (called an oral groove) to ingest food and an anal pore to excrete it. Contractile vacuoles allow the organism to excrete excess water. Cilia enable the organism to move.

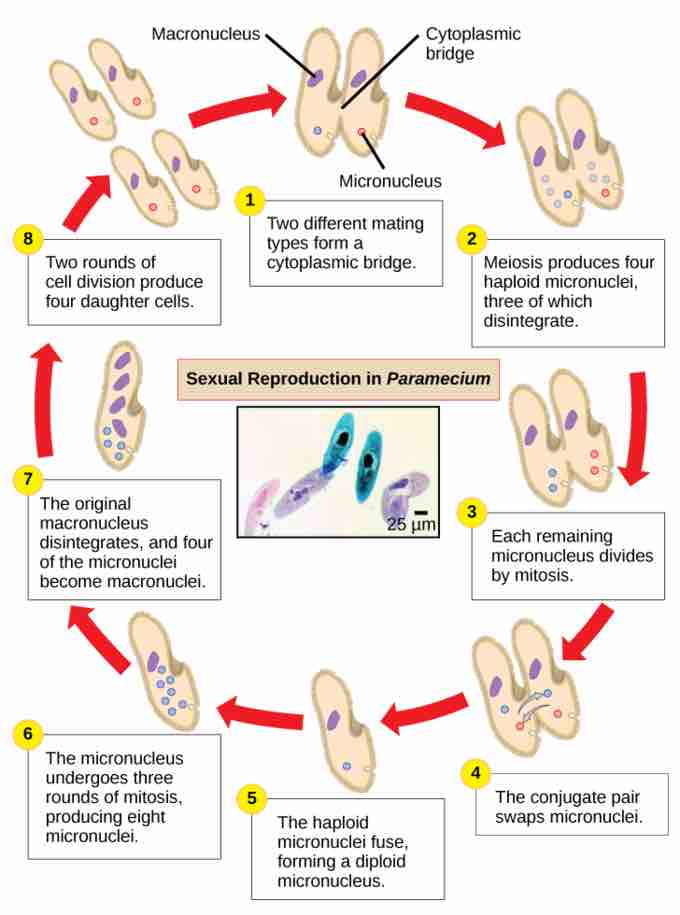

Paramecium has two nuclei, a macronucleus and a micronucleus, in each cell. The micronucleus is essential for sexual reproduction, whereas the macronucleus directs asexual binary fission and all other biological functions. The process of sexual reproduction in Paramecium underscores the importance of the micronucleus to these protists. Paramecium and most other ciliates reproduce sexually by conjugation. This process begins when two different mating types of Paramecium make physical contact and join with a cytoplasmic bridge . The diploid micronucleus in each cell then undergoes meiosis to produce four haploid micronuclei. Three of these degenerate in each cell, leaving one micronucleus that then undergoes mitosis, generating two haploid micronuclei. The cells each exchange one of these haploid nuclei and move away from each other. A similar process occurs in bacteria that have plasmids. Fusion of the haploid micronuclei generates a completely novel diploid pre-micronucleus in each conjugative cell. This pre-micronucleus undergoes three rounds of mitosis to produce eight copies, while the original macronucleus disintegrates. Four of the eight pre-micronuclei become full-fledged micronuclei, whereas the other four perform multiple rounds of DNA replication and then become new macronuclei. Two cell divisions then yield four new paramecia from each original conjugative cell.

Paramecium: sexual reproduction

The complex process of sexual reproduction in Paramecium creates eight daughter cells from two original cells. Each cell has a macronucleus and a micronucleus. During sexual reproduction, the macronucleus dissolves and is replaced by a micronucleus.