Uncertainty

Management specialists define uncertainty as a state of having limited knowledge such that it is impossible to exactly describe an existing state or future outcomes or to determine which of several possible outcomes will happen. It is still possible, however, to measure uncertainty—by assigning a probability to each possible state or outcome to estimate its likelihood.

In the past, strategic plans have often considered only the "official future," which was usually a straight-line graph of current trends carried into the future. Often the trend lines were generated by the accounting department and lacked discussions of demographics or qualitative differences in social conditions. These simplistic guesses can be good in some ways, but they fail to consider qualitative social changes that can affect an organization.

Instead of just following trend lines, scenarios focus on the collective impact of many factors. Scenario planning helps to understand how the various strands of a complex tapestry move if one or more threads are pulled. A list of possible causes, like a fault-tree analysis, tends to downplay the impact of isolated factors. When factors are explored together, certain combinations magnify the impact or likelihood of other factors. For instance, an increased trade deficit may trigger an economic recession, which in turn creates unemployment and reduces domestic production.

Fault tree

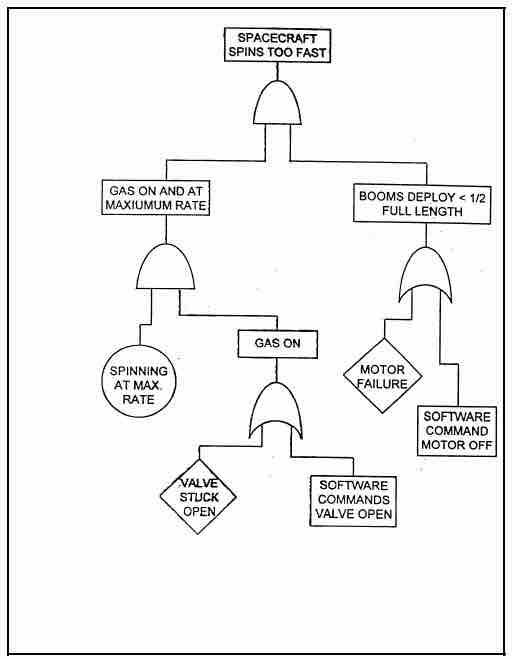

Fault trees can help outline possible outcomes. This fault tree visually lays out all the different steps at which something could go wrong in a spacecraft's flight, from the spacecraft itself spinning to fast to motor failure to a valve being stuck open.

Responding to Uncertainty

Organizations need to cope with issues that are too complex to be fully understood, yet significant decisions need to be made that are based on a limited understanding or limited information. There are several ways of dealing with this.

Be Iterative

The process of developing organizational strategy must be iterative. That is, it should involve toggling back and forth between questions about objectives, implementation planning, and resources. For example, an initial plan for a project may have to be adjusted if the budget changes.

Use Scenario Planning

Scenario planning starts by separating things believed to be known, at least to some degree, from those considered uncertain or unknowable. The first component, knowledge, includes trends, which cast the past forward, recognizing that the world possesses considerable momentum and continuity. The second component, uncertainties, involves indeterminable factors such as future interest rates, outcomes of political elections, rates of innovation, fads in markets, and so on. The art of scenario planning lies in blending the known and the unknown into a limited number of internally consistent views of the future that span a very wide range of possibilities.

Numerous organizations have applied scenario planning to a broad range of issues, from relatively simple, tactical decisions to the complex process of strategic planning and vision building. Scenario planning for business was originally established by Royal Dutch/Shell, which has used scenarios since the early 1970s as part of its process for generating and evaluating strategic options. Shell has been consistently better in its oil forecasts than other major oil companies, and predicted the overcapacity in the tanker business and Europe's petrochemicals earlier than its competitors.

Accept Uncertainty

It serves little purpose to pretend to anticipate every possible consequence of a corporate decision, every possible constraining or enabling factor, and every possible point of view. What matters for the purposes of strategic management is having a clear view, based on the best available evidence and on defensible assumptions, of what is possible to accomplish within the constraints of a given set of circumstances. As the situation changes, some opportunities for pursuing objectives will disappear and others will arise. Some implementation approaches will become impossible, while others, previously impossible or unimagined, will become viable. Strategic management adds little value, and may do harm, if organizational strategies are designed to be used as detailed and infallible blueprints for managers.