The Respiratory System

The primary function of the respiratory system is gas exchange between the external environment and an organism's circulatory system. In humans and other mammals, this exchange balances oxygenation of the blood with the removal of carbon dioxide and other metabolic wastes from the circulation.

As gas exchange occurs, the acid-base balance of the body is maintained as part of homeostasis. If proper ventilation is not maintained, two opposing conditions could occur: respiratory acidosis (a life threatening condition) and respiratory alkalosis.

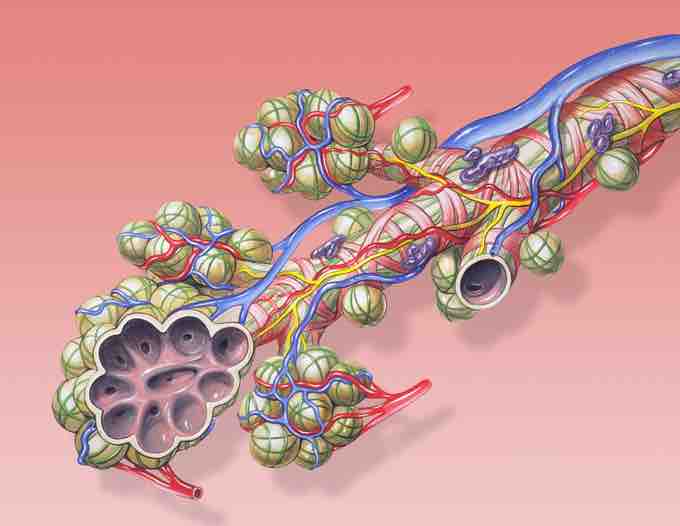

At the molecular level, gas exchange occurs in the alveoli—tiny sacs which are the basic functional component of the lungs. The alveolar epithelial tissue is extremely thin and permeable, allowing for gas exchange between the air inside the lungs and the capillaries of the blood stream. Air moves according to pressure differences, in which air flows from areas of high pressure to areas of low pressure.

Bronchial anatomy

The pulmonary alveoli are the terminal ends of the respiratory tree, outcropping from either alveolar sacs or alveolar ducts, which are both sites of gas exchange with the blood.

The Ventilation Rate

In respiratory physiology, ventilation rate is the rate at which gas enters or leaves the lung. There are several different terms used to describe the nuances of the ventilation rate.

- Minute Ventilation (VE): The amount of air entering the lungs per minute. It can be defined as tidal volume (the volume of air inhaled in a single breath) times the amount of breaths in a minute.

- Alveolar Ventilation (VA): The amount of gas per unit of time that reaches the alveoli (the functional part of the lungs where gas exchange occurs). It is defined as tidal volume minus dead space (the space in the lungs where gas exchange does not occur) times the respiratory rate.

- Dead Space Ventilation (VD): The amount of air per unit of time that doesn't reach the alveoli. It is defined as volume of dead space times the respiratory rate.

Dead space is any space that isn't involved in alveolar gas exchange itself, and it typically refers to parts of the lungs that are conducting zones for air, such as the trachea and bronchioles.

If someone breathes through a snorkeling mask, the length of their conducting zones increases, which increases dead space and reduces on alveolar ventilation. Feedback mechanisms increase the ventilation rate in such a case, but if dead space becomes too great, they won't be able to counteract the effect.

The ventilation rate is controlled by several centers of the autonomic nervous system in the brain, primarily the medulla and the pons.

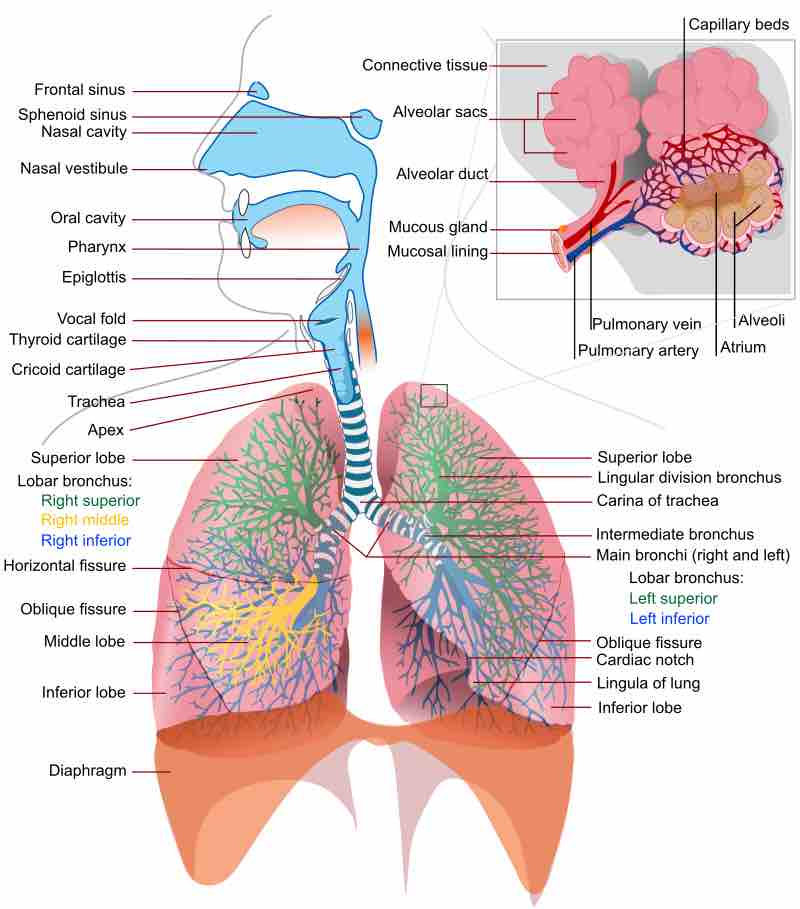

The human respiratory system

A complete, schematic view of the human respiratory system with its parts and functions.

Mechanisms of Inhalation

Inhalation is initiated by the activity of the diaphragm and supported by the external intercostal muscles. A normal human respiratory rate is 10 to 18 breaths per minute.

During vigorous inhalation (at rates exceeding 35 breaths per minute), or in approaching respiratory failure, accessory muscles—such as the sternocleidomastoid, platysma, and the scalene muscles of the neck—are recruited to help sustain the increased respiratory rate. Pectoral muscles and latissimus dorsi are also accessory muscles for the activity of the lungs.

Under normal conditions, the diaphragm is the primary driver of inhalation. When the diaphragm contracts, the rib cage expands and the contents of the abdomen are moved downward, resulting in a larger thoracic volume and negative pressure (with respect to atmospheric pressure) inside the thorax.

As air moves from zones of high pressure to zones of low pressure, the contraction of the diaphragm allows the air to enter the conducting zone (such as the trachea, bronchioles, etc.), where it is filtered, warmed, and humidified as it flows to the lungs.

Mechanisms of Exhalation

Exhalation is generally a passive process. The lungs have high degree of elastic recoil, so they rebound from the stretch of inhalation and air flows out until the pressures in the lungs and the atmosphere reach equilibrium.

The reason for the elastic recoil of the lung is the surface tension from water molecules on the epithelium of the lungs. A molecule called surfactant (secreted by the alveoli) prevents the surface tension from becoming too great and collapsing the lungs.

Active or forced exhalation is achieved by the abdominal and the internal intercostal muscles. During this process, air is forced or exhaled out. During forced exhalation, as when blowing out a candle, the expiratory muscles, including the abdominal muscles and internal intercostal muscles, generate abdominal and thoracic pressure that force air out of the lungs.

Forced exhalation is often used as an indicator to measure airway health, as people with obstructive lung diseases (such as emphysema, asthma, and bronchitis) will not be able to actively exhale as much as a healthy person because of obstruction in the conducting zones from inhlation, or from a loss of elastic recoil of the lungs.