Introduction

Separation of powers is a political doctrine originating from the writings of Montesquieu in The Spirit of the Laws in which he urges for a constitutional government with three separate branches of government . Each of the three branches would have defined powers to check the powers of the other branches. This idea was called separation of powers. This philosophy heavily influenced the writing of the United States Constitution, according to which the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of the United States government are kept distinct in order to prevent abuse of power. This United States form of separation of powers is associated with a system of checks and balances.

Montesquieu

Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu, who urged for a constitutional government with three separate branches of government.

Legislative Power

Congress has the sole power to legislate in the United States. Under the nondelegation doctrine, Congress may not delegate its lawmaking responsibilities to any other agency. One of the earliest cases involving the exact limits of non-delegation was Wayman v. Southard (1825). Congress had delegated to the courts the power to prescribe judicial procedure, and it was contended that in doing so Congress had unconstitutionally clothed the judiciary with legislative powers. While Chief Justice John Marshall conceded that the determination of rules of procedure was a legislative function, he distinguished between "important" subjects and mere details . Marshall wrote that "a general provision may be made, and power given to those who are to act under such general provisions, to fill up the details. "

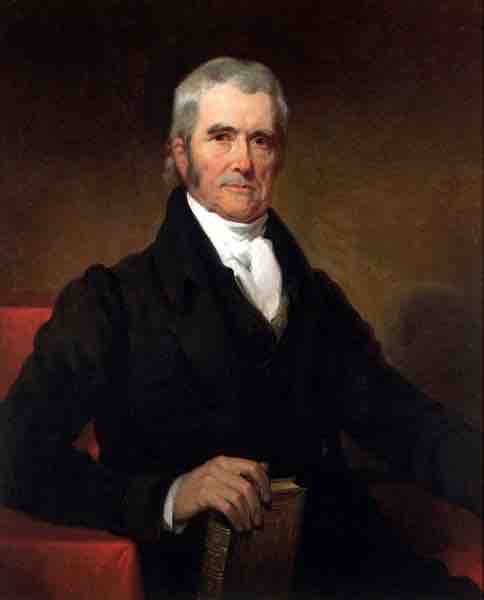

Portrait of John Marshall by Henry Inman (1832)

Henry Inman painted his original portrait of Chief Justice John Marshall in September 1831, when the jurist sat for Inman in Philadelphia. This painting is a copy of Inman's original that he made in 1832 for an engraver. John Marshall bought the painting for his daughter who passed it to her daughters. Marshall's granddaughters lent the portrait to the Virginia State Library in 1874 and the surviving granddaughter bequeathed it to the Library in 1920.

Executive Power

Executive power is vested, with exceptions and qualifications, in the President. By law, the president becomes the Commander in Chief of the Army, Navy, and Militia of several states when called into service, and has power to make treaties and appointments to office. The Constitution empowers the president to ensure the faithful execution of the laws made by Congress. Congress may terminate such appointments by impeachment, and restrict the president . The president's responsibility is to execute instructions given by Congress. Bodies such as the War Claims Commission, the Interstate Commerce Commission, and the Federal Trade Commission all have direct Congressional oversight.

The impeachment trial of President Clinton

Floor proceedings of the U.S. Senate, in session during the impeachment trial of Bill Clinton.

Judicial Power

Judicial power—the power to decide cases and controversies—is vested in the Supreme Court and inferior courts established by Congress. The judges must be appointed by the president with the advice and consent of the Senate, hold office during good behavior, and receive compensations that may not be diminished during their continuance in office. If a court's judges do not have such attributes, the court may not exercise the judicial power of the United States. Courts exercising the judicial power are called "constitutional courts. "

Alternative Model: The Parliamentary System

In a parliamentary system, the head of state is normally a different person from the head of government. This is in contrast to a presidential system in a democracy, where the head of state often is also the head of government, and most importantly: the executive branch does not derive its democratic legitimacy from the legislature. The Parliamentary system can be contrasted with a presidential system which operates under a stricter separation of powers, whereby the executive does not form part of, nor is appointed by, the parliamentary or legislative body. In such a system, congresses do not select or dismiss heads of governments, and governments cannot request an early dissolution as may be the case for parliaments. Since the legislative branch has more power over the executive branch in a parliamentary system, a notable amount of studies by political scientists have shown that parliamentary systems show lower levels of corruption than presidential systems of government.