As part of their justification for leaving the Union after the election of 1860, secessionists argued that the Constitution was a compact among states that could be abandoned at any time without consultation, and that each state reserved the right to secede from the compact. South Carolina invoked the Declaration of Independence to defend their right to secede from the Union, seeing their declaration of secession as a comparable document. Seven Deep South states passed secession ordinances by February 1861 prior to Abraham Lincoln acceding to office. Declaring themselves the Confederate States of America, these seven states elected Jefferson Davis as their provisional president; declared Montgomery, Alabama, the nation's capital; and began raising an army.

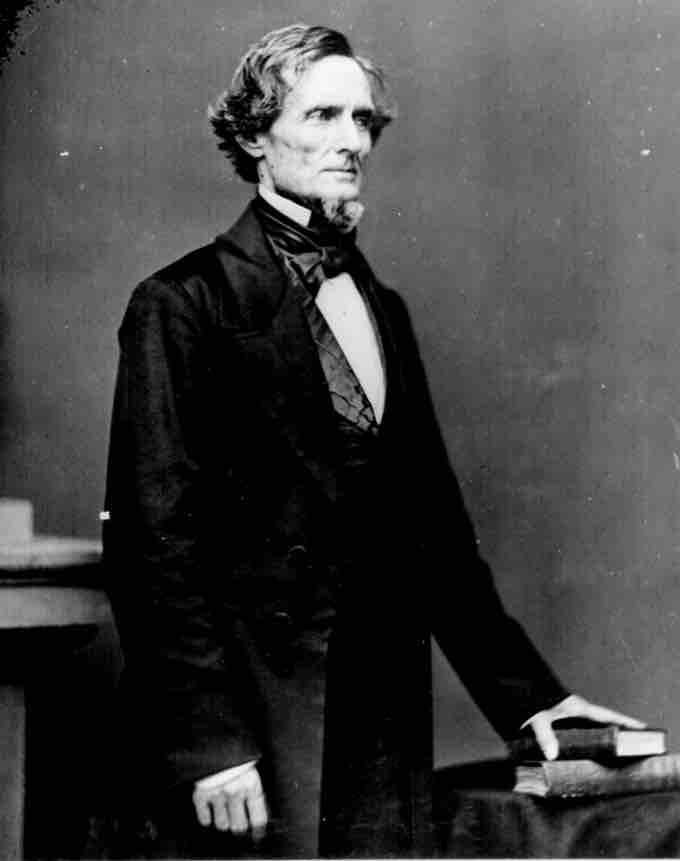

Jefferson Davis

Davis became the provisional president of the Confederate States of America following secession.

Responses to Secession

In the aftermath of the 1860 presidential election, sitting President Buchanan did little to halt the wave of Southern secession. Believing that the key to good government was restraint, he refused to deploy troops or additional artillery to federal properties under threat. Paradoxically, in his final address to Congress, Buchanan denied that states had a right to secede from the Union, but also held that the federal government could not prevent secession from happening through the use of force. Instead, Buchanan proposed a constitutional amendment reaffirming slavery as a protected American institution, strengthening existing fugitive slave laws, and preventing Congress from legislating against the expansion of slavery into federal territories.

In Congress, many proposals were drafted in an attempt to appease the Southern seceding states. The Crittenden Compromise of December 1860 proposed that the old Missouri Compromise latitude boundary line be extended west to the Pacific. Unfortunately, this proposal was in direct conflict with the stated policies of the Republican Party and president-elect Lincoln, and Southern leaders refused to agree to the compromise without a full endorsement from Republicans. This resulted in a stalemate between both sides, and the Crittenden Compromise was ultimately voted down in the Senate.

Davis's inauguration, 1861

Jefferson Davis's inauguration, Montgomery, Alabama.

On February 4, 1861, a Peace Conference convened in Washington, D.C., comprised of more than 100 of the leading politicians of the antebellum period. Many attended with the belief that they could avert the crisis toward which secession was heading, whereas some attended in order to safeguard their own sectional interests in what they believed to be an unstoppable escalation of hostilities. Delegations from Arkansas, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, California, Oregon, and all of the Deep South states were not present at the conference.

Lincoln also initially tried to pacify the seceding states in his presidential inaugural address, in which he explicitly promised to preserve slavery in the states it already existed in and implied support for the proposed Corwin Amendment, which would have given further protections to slavery in the Constitution. However, efforts by the Confederate States to forcibly remove U.S. troops and federal presence from its territory, culminating in the Battle of Fort Sumter, pushed the two factions irreversibly toward war.

Progression of Hostilities

After the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, and Lincoln's subsequent call for troops on April 15, four more states declared their secession. By spring 1861, the Confederacy was composed of South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina. Although slaveholding Delaware and Maryland did not secede, citizens from those states exhibited divided loyalties, and Lincoln implemented a system of compensated emancipation and slave confiscation from "disloyal citizens" in these border states during the Civil War.

The U.S. government did not declare war on the Confederate States, but it did conduct military efforts beginning with a presidential proclamation issued April 15, 1861, which called for troops to recapture Southern forts and suppress a Southern rebellion. Immediately following Fort Sumter, the Confederate Congress declared war against the United States and the Civil War officially began.

During the four years of its wartime existence, the Confederacy asserted its independence by appointing dozens of diplomatic agents abroad. The U.S. government, on the other hand, regarded the organization of Confederate states a rebellion and refused any formal recognition of their government. The United States issued warnings to Europe (particularly Britain) that threatened hostile relations if the Confederacy was recognized internationally. Throughout the early years of the war, British foreign secretary Lord John Russell, Napoleon III of France, and other foreign leaders showed interest in recognizing the Confederacy, or at least in a mediation in the war. However, Europe remained largely neutral in the Civil War, unwilling to lose trading relations with the United States. At the same time, foreign governments curiously watched the political evolution of the Confederacy and sent military observers to assess Confederate autonomy in the event that the South prevailed in its fight for nationhood.