Constitutional Convention

The Constitutional Convention, which took place in Philadelphia from May 14 to September 17, 1787, was one of the most significant events in the formation of the United States. Twelve of the 13 states, excepting Rhode Island, sent delegates to address the issue of governing the United States. Following its independence from Great Britain, the nation had been operating under the Articles of Confederation, which defined the federal government. Although the convention was called for revising the Articles of Confederation, many of the convention's proponents (including James Madison and Alexander Hamilton) intended to create a completely new government.

On May 25, the delegations convened in the Pennsylvania State House, and George Washington was unanimously elected as president of the convention. During the following months, several debates shaped what would eventually become the United States Constitution.

Determining Representation: Virginia and New Jersey Plans

Of first importance in the convention was to adopt an efficient system of federal representation; however, delegates disagreed about how to best achieve this. Delegates presented several proposals outlining various political structures. Drawing on British common law and the writings of Enlightenment political philosophers, most of these plans provided for some form of separation between a legislative, executive, and judicial power.

The delegates agreed that the executive office should consist of a single individual elected for a fixed term, in which foreign affairs, control over the armed forces, and appointment of federal officers (including Supreme Court judges) would be consigned. Delegates also accepted the need for either a unicameral (one-house) or a bicameral (two-house) legislature. However, they debated about how many legislators were to be voted into office and what qualifications were needed to hold a seat in a particular house.

Larger state delegates favored a system with proportional representation in both houses; the greater the population of voters in a given state, the more federal representatives would be allotted to that state in Congress. Delegates from these states supported the Virginia Plan, crafted by James Madison, which included a system of proportional representation in Congress as well as an extension of congressional powers. This plan also proposed a bicameral legislature. Members of one of the two legislative chambers would be elected by the people, and members of that chamber would then elect those of the second chamber from nominations submitted by state legislatures. The executive would be chosen by the legislative branch, which would have the power to negate state laws if they were deemed incompatible with the articles of union. The concept of checks and balances was embodied in a provision that legislative acts could be vetoed by a council composed of the executive and selected members of the judicial branch.

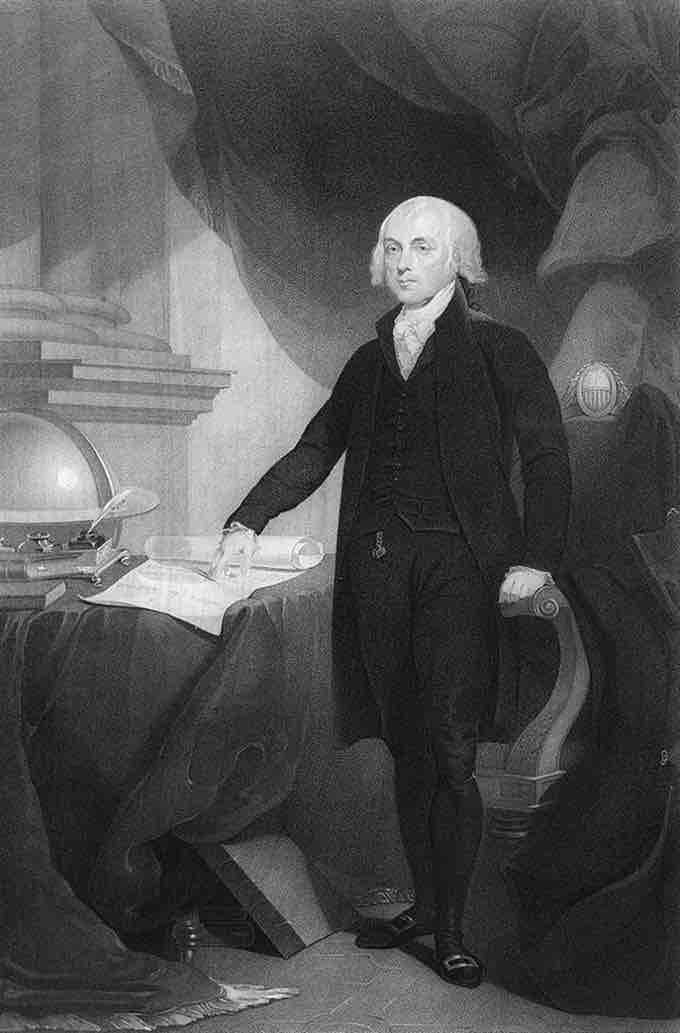

James Madison

James Madison authored the Virginia Plan.

Delegates from small states, however, demanded a system of equal representation, whereby the number of representatives from each state would be fixed, regardless of population size. This system of equal representation was detailed in William Paterson's New Jersey Plan. This plan proposed a unicameral legislature in which each state, regardless of size, would have one vote. The plan also proposed that Congress would elect a federal executive branch, consisting of multiple people, who could not be re-elected and could be recalled by Congress when requested by the majority of state executives.

Connecticut Compromise

Debate over the Virginia vs. New Jersey Plans was contentious and almost threatened to shut the convention down. However, the Connecticut Compromise proposed by Roger Sherman outlined a system of bicameral legislation that included both proportional and equal representation. Also known as the “Great Compromise,” it allowed for both plans to work together and defined the legislative structure and representation of each state under the Constitution. The Compromise indicated that each state would be given equal representation (as per the New Jersey Plan) in one house of Congress and proportional representation (as per the Virginia Plan) in the other. In the Senate, each state would have two seats. In the House of Representatives, the number of seats would depend on the state's population.

To further gain the support of the larger states, Benjamin Franklin made two important modifications to this compromise, which was sufficient to win approval for the overall Constitution. He added the requirement that revenue bills would originate in the House, although this language was later modified further so that revenue bills could be modified in the Senate. Franklin also specified that each state (rather than each state delegation) was to receive one vote and that each state would have multiple senators. Because senators would each be voting individually, rather than as a bloc by state, as delegates always had, they would act as free agents on behalf of their state, rather than as mere agents of the state legislatures.

While northern delegations wanted only free citizens to count toward representation, southern delegations wanted to include slaves as a way of increasing their states’ representation in government. The Three-Fifths Compromise, which assessed population by adding the number of free persons to three-fifths of the number of "all other persons" was agreed to without serious dispute. Under this compromise, each slave was counted as three-fifths of a person, allowing the slave states to include a portion of their enslaved population when allocating representation. The free states found the compromise negligible when compared with the ultimate goal of writing a new governing document, and slave states were satisfied by this provision and agreed to support the plan.

Resolving Further Questions

Once the convention had finished amending the first draft of the Constitution, a new set of unresolved questions was sent to several different committees for resolution. The committees shortened the President's term from 7 years to 4 years, freed him to seek reelection, and moved impeachment trials from the courts to the Senate. They also created the position of Vice President, whose only role was to succeed the President, if necessary, and preside over the Senate.

Once the final modifications had been made, the Committee of Style and Arrangement produced the final version of the Constitution. Not all of the delegates were pleased with the results; 13 delegates left before the signing ceremony and three of those remaining refused to sign. George Mason of Virginia said he would not support the Constitution unless it included a Bill of Rights. While the Bill of Rights was not included in the Constitution submitted to the states for ratification, many states ratified the Constitution with the understanding that a Bill of Rights would soon follow. Thirty-nine of the 55 delegates ended up signing, although it is likely that none were completely satisfied.

US Postage Stamp

U.S. Postage, Issue of 1937, depicting Delegates at the signing of the U.S. Constitution, engraving after a painting by Junius Brutus Stearns.