THE MANHATTAN PROJECT

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program, led by the United States with participation from the United Kingdom and Canada, that produced the first atomic bomb during World War II. It was also charged with gathering intelligence on the German nuclear energy project. Through Operation Alsos, Manhattan Project personnel served in Europe, sometimes behind enemy lines, where they gathered nuclear materials and rounded up German scientists. In the immediate postwar years, the Manhattan Project conducted weapons testing at Bikini Atoll as part of Operation Crossroads.

From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army Corps of Engineers. The Army component of the project was designated the Manhattan District; Manhattan gradually superseded the official code name, Development of Substitute Materials, for the entire project. Along the way, the Manhattan Project absorbed its earlier British counterpart, Tube Alloys.

The Manhattan Project began modestly in 1939, but grew to employ more than 130,000 (although some estimate that as many as 160,000) people and cost nearly US 2 billion (roughly equivalent to 25.8 billion as of 2012). Research and production took place at more than 30 sites, some secret, across the United States, the United Kingdom and Canada. It maintained control over American atomic weapons research and production until the formation of the United States Atomic Energy Commission in January 1947.

PRODUCING THE BOMB

Two types of atomic bomb were developed during the war. A relatively simple gun-type fission weapon was made using uranium while a more complex plutonium implosion-type weapon was designed concurrently. For the Gun-Type weapon development uranium-235 (an isotope that makes up only 0.7 percent of natural uranium) was required. Chemically identical to the most common isotope, uranium-238, and with almost the same mass, it proved difficult to separate the two. Most of this work was performed at Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

In parallel with the work on uranium was an effort to produce plutonium. Reactors were constructed at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Hanford, Washington, in which uranium was irradiated and transmuted into plutonium. The plutonium was then chemically separated from the uranium. The gun-type design proved impractical to use with plutonium so a more complex implosion-type weapon was developed in a concerted design and construction effort at the project's weapons research and design laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico.

THE BOMBINGS OF HIROSHIMA AND NAGASAKI

Following a firebombing campaign that destroyed many Japanese cities, the Allies prepared for a costly invasion of Japan. The war in Europe ended when Nazi Germany signed its instrument of surrender on May 8, but the Pacific War continued. Together with the United Kingdom and the Republic of China, the United States called for a surrender of Japan in the Potsdam Declaration of July 26, 1945, threatening Japan with "prompt and utter destruction." The Japanese government ignored this ultimatum.

On August 6, the U.S. dropped a uranium gun-type atomic bomb (Little Boy) on the city of Hiroshima. American President Harry S. Truman called for Japan's surrender 16 hours later, warning them to "expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth." Three days later, on August 9, the U.S. dropped a plutonium implosion-type bomb (Fat Man) on the city of Nagasaki.

CASULTIES AND DAMAGES

In Hiroshima, an area of approximately 4.7 square miles (12 km2) was destroyed. Japanese officials determined that 69% of Hiroshima's buildings were destroyed and another 6–7% damaged. About 70,000 to 80,000 people, of whom 20,000 were Japanese combatants and 20,000 were Korean slave laborers, or some 30% of the population of Hiroshima, were killed immediately, and another 70,000 injured. The bomb in Nagasaki was dropped over the city's industrial valley midway between the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works in the south and the Mitsubishi-Urakami Ordnance Works in the north. The resulting explosion had a blast yield equivalent to 21 kilotons of TNT but was confined to the Urakami Valley and a major portion of the city was protected by the intervening hills, resulting in the destruction of about 44% of the city. The bombing also crippled the city's industrial production extensively and killed 23,200–28,200 Japanese industrial workers and 150 Japanese soldiers. Overall, an estimated 35,000–40,000 people were killed and 60,000 injured. Estimates vary greatly but within the first two to four months of the bombings, the acute effects of the atomic bombings killed 90,000–146,000 people in Hiroshima and 39,000–80,000 in Nagasaki. Many died from the effect of burns, radiation sickness, and other injuries, compounded by illness and malnutrition. In both cities, most of the dead were civilians, although Hiroshima had a sizable military garrison.

The Atomic Bomb's devastation

Photo of what became later Hiroshima Peace Memorial among the ruins of buildings in Hiroshima, in early October, 1945.

Following the bombings, Emperor Hirohito intervened and ordered the Supreme Council for the Direction of the War to accept the terms the Allies had set down in the Potsdam Declaration for ending the war. After several more days of behind-the-scenes negotiations and a failed coup d'état, Emperor Hirohito gave a recorded radio address across the Empire on August 15. In the radio address, he announced the surrender of Japan to the Allies.

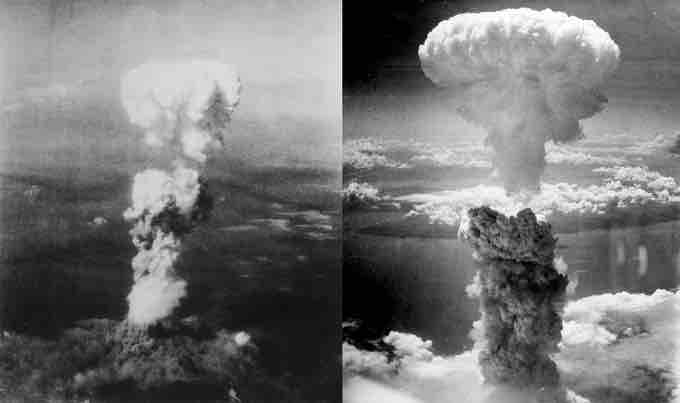

Atomic Bombing of Japan

Atomic bomb mushroom clouds over Hiroshima (left) and Nagasaki (right).