The Rise of Abolitionism

Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, abolitionism—a movement to end slavery—intensified throughout the United States. In the 1850s, slavery was established legally in the 15 states constituting the American South. It remained especially strong in plantation areas where crops such as cotton, sugar, tobacco, and hemp were essential exports. By 1860, the slave population in the United States had grown to 4 million. While American abolitionism strengthened in the North, support for slavery held strong among white southerners, who profited so greatly from the system of enslaved labor that slavery itself became intertwined with the national economy. The banking, shipping, and manufacturing industries of New York City all had strong economic interests in slavery, as did other major cities in the North.

Leading Activists

Notable African-American activists included former slaves such as Frederick Douglass and David Walker and free African Americans such as brothers Charles Henry Langston and John Mercer Langston, who helped found the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society. Other abolitionists included writers such as John Greenleaf Whittier and Harriet Beecher Stowe. The white abolitionist movement in the North was led by social reformers, especially William Lloyd Garrison, founder of the American Anti-Slavery Society. The Society fragmented in the 1830s and 40s into groups that included the Liberty Party, the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, the American Missionary Association, and the Church Anti-Slavery Society. A few abolitionists, such as John Brown, favored the use of armed force to encourage uprisings among slaves. Brown led two actions for the purpose of abolishing slavery—the Pottawatomie Massacre in Bleeding Kansas in 1856 and an unsuccessful raid at Harpers Ferry in 1859.

Abolitionist Arguments

Antislavery as a principle was far more than simply the wish to limit slavery. Most northerners recognized that the Constitution did not allow the federal government to intervene in the slavery-laden South. Historians traditionally distinguish between "gradualists," moderate antislavery reformers who concentrated on stopping the spread of slavery, and "immediatists," or radical abolitionists (such as William Lloyd Garrison) whose demands for unconditional emancipation often merged with their concern for African-American civil rights.

Most abolitionists tried to raise public support by citing the unlawfulness of slavery. Some abolitionists claimed that slavery was not only criminal, but also a sin. Additionally, they criticized slave owners for using black women as concubines. This movement to tout the immorality of slavery gained momentum with the widespread publication of Uncle Tom's Cabin in the North in 1852. The abolitionist movement was further strengthened by the efforts of free African Americans, especially in the black church, who argued that the old biblical justifications for slavery contradicted the New Testament. Abolitionists pointed to evidence of the abuses of slavery to strengthen their arguments.

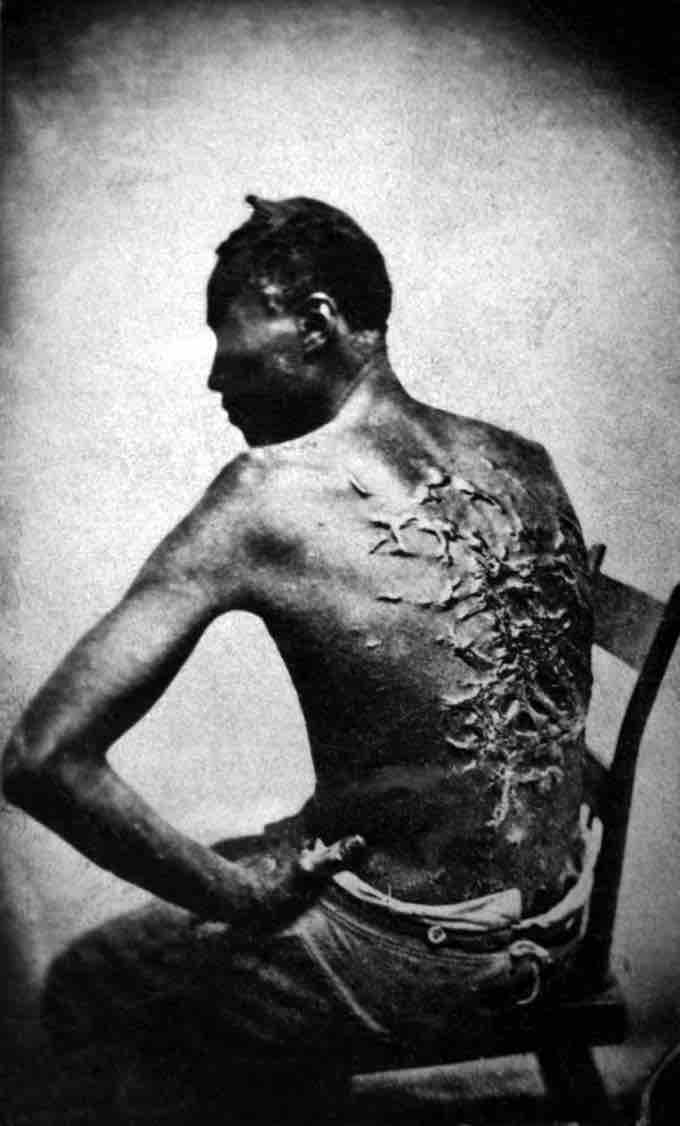

Slavery abuses

Abolitionists used evidence such as the scars on the back of this former slave named Peter to speak eloquently about the abuses of slavery.

The Republican Party wanted to achieve the gradual extinction of slavery by market forces, based on the belief that free labor was superior to slave labor. Believing that restricting slavery to the South and refusing to let it expand would eventually cause the institution to die out, the party adopted a "free soil" platform.

The heated sectional controversy between the North and the South reached new levels of intensity in the 1850s. Southerners and northerners grew ever more antagonistic as they debated the expansion of slavery in the West. The notorious confrontation between Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina and Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner illustrates the contempt between extremists on both sides. The “Caning of Sumner” in May 1856 followed a speech given by Sumner two days earlier, in which he condemned slavery in no uncertain terms, declaring: “[Admitting Kansas as a slave state] is the rape of a virgin territory, compelling it to the hateful embrace of slavery; and it may be clearly traced to a depraved longing for a new slave state, the hideous offspring of such a crime, in the hope of adding to the power of slavery in the national government.” Sumner criticized proslavery legislators, particularly attacking a fellow senator and relative of Preston Brooks. Brooks responded by beating Sumner with a cane, a thrashing that southerners celebrated as a defense of gentlemanly honor and their way of life. The episode highlights the violent clash between pro- and antislavery factions in the 1850s, a conflict that would eventually lead to the traumatic unraveling of American democracy and civil war.

The Argument for Colonization

In the early part of the nineteenth century, a variety of organizations were founded that advocated for the moving of black people from the United States to locations where they would enjoy greater freedom. Some endorsed colonization in Africa, while others advocated emigration. During the 1820s and 30s, the American Colonization Society (ACS, or the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America) was the primary advocate of returning free African Americans to what was considered greater freedom in Africa. The ACS was mostly composed of Quakers and slaveholders who disagreed on the issue of slavery but found common ground in supporting repatriation. Colonization ignored the fact that many freed slaves, having lived in America for several generations, considered it their home, and preferred full rights in the United States over emigration. Colonization also lost appeal based on the logistics of relocating millions of slaves outside of the country. In 1821, the ACS established the colony of Liberia in Africa and assisted the emigration of thousands of former African-American slaves and free blacks (with legislated limits) from the United States. Many white people deemed this preferable to emancipation in the United States.