Fall and Occupation of Atlanta

On September 1, 1864, Confederate forces evacuated Atlanta, and the following day, the city was officially surrendered to Union forces. Over those two days and nights, explosions and fires could be heard and seen across the city as 81 railcars filled with ammunition and Confederate military supplies were destroyed. By September 3, Union forces began moving into the city, and civilians were ordered to leave. Private homes were repurposed for federal use, adding to the stress felt across the local population as military control spread. Union Major General William Tecumseh Sherman and Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant believed that the Civil War would end only if the Confederacy's strategic, economic, and psychological capacity for warfare were decisively broken. Sherman therefore applied the principles of scorched earth throughout his successful Atlanta campaign from May to September of 1864; he ordered his troops to burn crops, kill livestock, and consume supplies. Finally he destroyed civilian infrastructure along his path of advance. The recent reelection of President Abraham Lincoln ensured that no short-term political pressure would restrain these tactics. Federal forces occupied Atlanta until November 15–16, when Sherman’s “March to the Sea” began.

The "March to the Sea"

Sherman's "March to the Sea" is the name commonly given to the Savannah Campaign conducted around Georgia from November 15, 1864, to December 21, 1864, by Major General William Tecumseh Sherman of the Union Army. The campaign began with Sherman's troops leaving the captured city of Atlanta, Georgia, on November 16 and ended with the capture of the port of Savannah on December 21. It inflicted significant damage, particularly to industry and infrastructure.

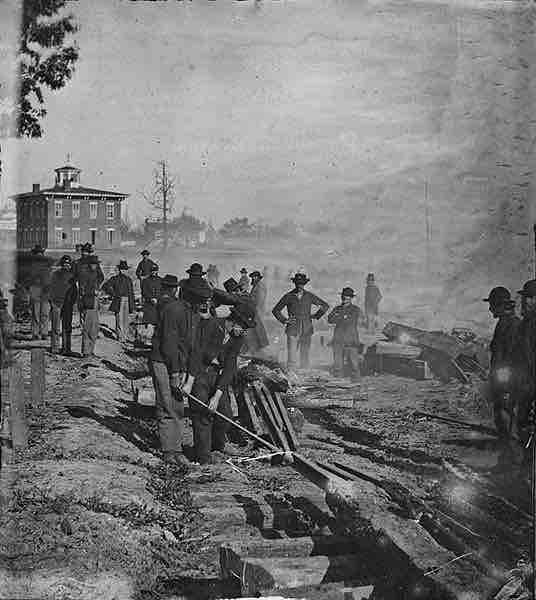

Sherman's men destroying railroad tracks. Atlanta, Georgia.

Sherman's men destroying a railroad in Atlanta.

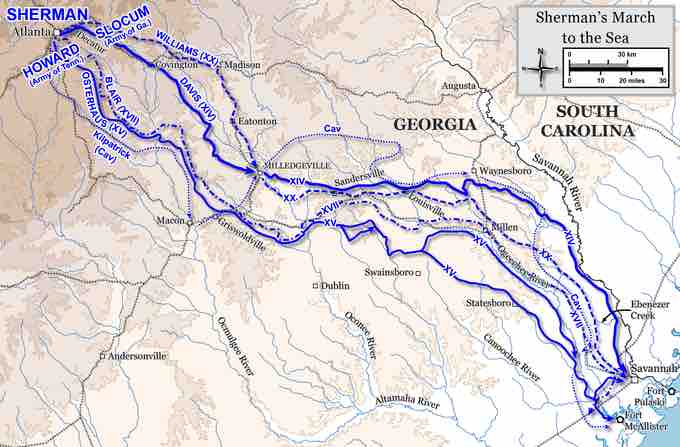

Sherman's March to the Sea

This map shows the Savannah Campaign (Sherman's March to the Sea) during the American Civil War.

The second objective of the campaign was more traditional. Grant's armies in Virginia remained in a stalemate against Robert E. Lee's army, besieged in Petersburg, Virginia. By moving in Lee's rear and performing a massive turning movement against him, Sherman possibly could increase pressure on Lee, allowing Grant the opportunity to break through, or at least keep Southern reinforcements away from Virginia.

Scorched Earth and the Capture of Savannah

The campaign was similar to Grant's innovative and successful Vicksburg Campaign in that Sherman's armies reduced their need for traditional supply lines by "living off the land" after consuming their 20 days of rations. Foragers, known as "bummers," provided food seized from local farms to soldiers while they destroyed the railroads, manufacturing, and agricultural infrastructure of Georgia. In planning for the march, Sherman used livestock and crop production data from the 1860 census to lead his troops through areas where he believed they would be able to forage most effectively.

Sherman's armies reached the outskirts of Savannah on December 10 but found 10,000 Confederate troops entrenched in good positions. The soldiers had flooded the surrounding rice fields, leaving only narrow causeways available to approach the city. Sherman was blocked from linking up with the U.S. Navy as he had planned, so he dispatched cavalry to Fort McAllister, guarding the Ogeechee River, in hopes of unblocking his route and obtaining the supplies that awaited him on the Navy ships. On December 13, troops stormed the fort in the Battle of Fort McAllister and captured it within 15 minutes. Now that Sherman had connected to the navy fleet he was able to obtain the supplies and siege artillery he required to invade Savannah.

After capturing Savannah, Sherman telegraphed to President Lincoln, "I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the City of Savannah, with one hundred and fifty guns and plenty of ammunition, also about twenty-five thousand bales of cotton." On December 26, the president replied in a letter: "Many, many thanks for your Christmas gift—the capture of Savannah." From Savannah, Sherman marched north in the spring through the Carolinas, intending to complete his turning movement and combine his armies with Grant's against Lee. After a successful two-month campaign, Sherman accepted the surrender of General Joseph E. Johnston and his forces in North Carolina on April 26, 1865.

Sherman's scorched earth policies remain highly controversial, and many Southerners have long reviled Sherman's memory. Many slaves, however, welcomed him as a liberator and left their plantations to follow his armies. The March to the Sea was devastating to Georgia and the Confederacy. Sherman himself estimated that the campaign had inflicted $100 million in damages, or about 1.378 billion in 2010 dollars.

Sherman's March

This engraving by Alexander Hay Ritchie depicts Sherman's March.