Background

During the American Revolution, the United States and France signed the Treaty of Alliance, in which both nations pledged mutual military support against Britain. By the mid 1790s, most Federalists considered the Treaty of Alliance to be null and void, as the French Revolution had toppled the regime that entered into the original agreement with the United States. In a practical sense, Washington, Adams, and other Federalists believed that the United States was too weak to enter into the French revolutionary wars and had too much at stake.

To that end, Washington issued a Proclamation of Neutrality in 1795, which declared the United States free from any military obligation to European nations and stipulated that the United States would continue to trade with both France and Britain. However, the U.S. government also negotiated Jay's Treaty with Britain, which—in addition to clarifying several disputes that remained unaddressed in the Treaty of Paris—included several economic agreements that gave Britain special trading status with the United States.

The XYZ Affair

The Proclamation of Neutrality and Jay's Treaty both outraged France, and the French navy began seizing American ships and harassing American traders in Caribbean and European ports. This resulted in substantial losses for American shipping. The French seized 316 American merchant ships by June of 1797, and the French Republic refused to receive the new U.S. minister Charles Pinckney when he arrived in Paris in December of 1796.

When Adams sent a three-man delegation—Charles Pinckney, John Marshall, and Elbridge Gerry—to Paris to negotiate a peace agreement with France, French agents demanded major concessions from the United States as a condition for continuing diplomatic relations. These included a demand for 50,000 pounds sterling and a $250,000 personal bribe to the French foreign minister, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand. The United States had offered France many of the same provisions found in Jay's Treaty with Britain, but France reacted by deporting Marshall and Pinckney—both key Federalists—back to the United States and refusing any proposal that would involve these two delegates.

In April of 1798, President Adams informed Congress of how France had demanded bribes from the United States before it would discuss any peace settlement. Because Adams omitted the names of the French agents in the dispatches, referring to them as "X, Y, and Z," the incident became known as the "XYZ Affair." This led to widespread outrage and swelling anti-French sentiment (or Francophobia) in American public opinion.

The Quasi-War

Francophobia in the American public exploded, and support for war with France, led by Hamilton and the Federalists, mounted. War seemed inevitable as the French continued to seize private American ships in the Atlantic, Mediterranean, and Caribbean, and Congress authorized Adams to begin to build up the army and navy. However, Adams continued to hope for a peaceful settlement with France and avoided pushing Congress toward a formal declaration of war.

Instead, the Quasi-War began in July of 1798. While there was no formal declaration of war, the conflict escalated, with both sides capturing ships and the expanding U.S. navy slowly pushing the French out of the West Indian trade system in the Caribbean. The success of these U.S. naval endeavors was due to the fact that Congress authorized President Adams to acquire, develop, and arm numerous new warships and train naval sailors. Hostilities continued until France experienced another regime change in 1799. American commissioners then negotiated the Treaty of Mortefontaine with Napoleon's ministers in September 1800, which ended all hostilities.

Effects

The Quasi-War strengthened the U.S. navy, helped expand American commercial networks in the Caribbean, and enabled the development of the military powers necessary to protect these networks. This was a victory for the Federalists who sought to establish a strong American economic and naval presence in the Atlantic. However, the Quasi-War also had a negative affect on political relations between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. Democratic-Republicans were pro-French and were dismayed by the Quasi-War, often voicing their opinions in political speeches and writings. In response, Adams and the Federalist Congress passed the unpopular Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798. This legislation, among other restrictions, prohibited treasonable or "malicious" speech against the government. Essentially, these acts restricted the free-speech rights of the opposing Democratic-Republicans by censoring anti-Federalist writings. As a result of the ensuing backlash against the Alien and Sedition Acts and Adams's failure to unite the Federalists for a strong electoral campaign, Adams lost the 1800 election.

The Quasi-War remains an ambiguous precedent for the separation of military powers between the executive and legislative branches. Although Congress never officially declared war, it did authorize Adams to build a navy for the explicit purpose of attacking French warships that sought to capture American merchant vessels. However, Adams also demonstrated widespread initiative as commander in chief during the Quasi-War, authorizing—without congressional approval—the capture of any ships sailing to and from French ports. This ambiguity over the distribution of war powers between the executive branch and Congress has persisted well into the twenty-first century. In order to contextualize their arguments, advocates for and against the broad interpretation of executive military authority often draw on the Quasi-War as an example.

The Quasi-War

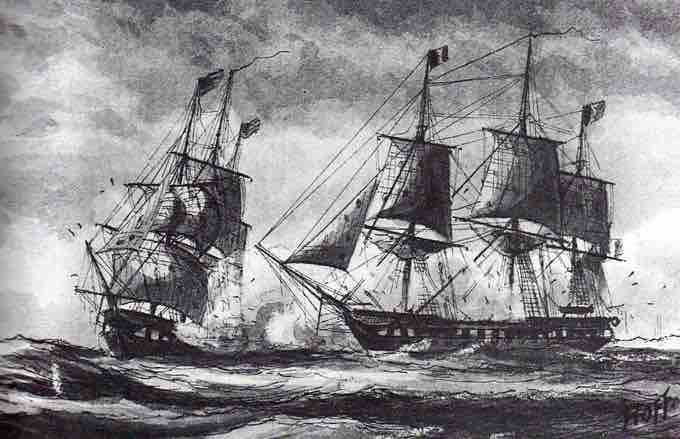

The USS Constellation and L'Insurgente battle during the Quasi-War between the United States and France.