Norman Kings after the Conquest

At the death of William the Conqueror in 1087, his lands were divided into two parts. His Norman lands went to his eldest son, Robert Curthose and his English lands to his second son, William Rufus. This presented a dilemma for those nobles who held land on both sides of the English Channel, who decided to unite England and Normandy once more under one ruler. The pursuit of this aim led them to revolt against William in favor of Robert in the Rebellion of 1088. As Robert failed to appear in England to rally his supporters, William won the support of the English lords with silver and promises of better government, and defeated the rebellion. William died while hunting in 1100.

Despite Robert's rival claims to William's land, his younger brother Henry immediately seized power in England. Robert, who invaded in 1101, disputed Henry's control of England. This military campaign ended in a negotiated settlement that confirmed Henry as king. The peace was short lived, and Henry invaded the Duchy of Normandy in 1105 and 1106, finally defeating Robert at the Battle of Tinchebray.

Henry I of England named his daughter Matilda his heir, but when he died in 1135 Matilda was far from England in Anjou or Maine, while her cousin Stephen was closer in Boulogne, giving him the advantage he needed to race to England and have himself crowned and anointed king of England. After Stephen's death in 1154, Henry II succeeded as the first Angevin king of England, so-called because he was also the Count of Anjou in northern France. He therefore added England to his extensive holdings in Normandy and Aquitaine. England became a key part of a loose-knit assemblage of lands spread across Western Europe, later termed the Angevin Empire. Henry was succeeded by his third son, Richard, whose reputation for martial prowess won him the epithet "Lionheart." When Richard died, his brother John—Henry’s fifth and only surviving son—took the throne

Magna Carta

Over the course of King John's reign (1199-1216), a combination of higher taxes, unsuccessful wars, and conflict with the pope had made him unpopular with his barons. In 1215 some of the most important barons engaged in open rebellion against their king. King John met with the leaders of the barons, along with their French and Scot allies, to seal the Great Charter (Magna Carta in Latin), which imposed legal limits on the king's personal powers. It was sealed under oath by King John at Runnymede, on the bank of the River Thames near Windsor, England, on June 15, 1215. It promised the protection of church rights, protection for the barons from illegal imprisonment, access to swift justice, and limitations on feudal payments to the Crown, to be implemented through a council of twenty-five barons.

Magna Carta

One of four known surviving original copies of the Magna Carta of 2015, written in iron gall ink on parchment in medieval Latin, authenticated with the Great Seal of King John. This document is held at the British Library.

Background

Although the kingdom had a robust administrative system, the nature of government under the Angevin monarchs was ill-defined and uncertain. John and his predecessors had ruled using the principle of vis et voluntas, or "force and will," making executive and sometimes arbitrary decisions, often justified on the basis that a king was above the law. Many contemporary writers believed that monarchs should rule in accordance with the custom and the law, with the counsel of the leading members of the realm, but there was no model for what should happen if a king refused to do so.

John had lost most of his ancestral lands in France to King Philip II in 1204 and had struggled to regain them for many years, raising extensive taxes on the barons to accumulate money to fight a war that ultimately ended in expensive failure in 1214. Following the defeat of his allies at the Battle of Bouvines, John had to sue for peace and pay compensation. John was already personally unpopular with a number of the barons, many of whom owed money to the Crown, and little trust existed between the two sides. A triumph would have strengthened his position, but within a few months after his unsuccessful return from France, John found that rebel barons in the north and east of England were organizing resistance to his rule.

John met the rebel leaders at Runnymede, a water-meadow on the south bank of the River Thames, on June 10, 1215. Here the rebels presented John with their draft demands for reform, the "Articles of the Barons." Stephen Langton's pragmatic efforts at mediation over the next ten days turned these incomplete demands into a charter capturing the proposed peace agreement; a few years later, this agreement was renamed Magna Carta, meaning "Great Charter."

Clause 61

The 1215 document contained a large section that is now called clause 61 (the clauses were not originally numbered). This section established a committee of twenty-five barons who could at any time meet and overrule the will of the king if he defied the provisions of the charter, and could seize his castles and possessions if it was considered necessary. It contained a commitment from John that he would "seek to obtain nothing from anyone, in our own person or through someone else, whereby any of these grants or liberties may be revoked or diminished."

Clause 61 was a serious challenge to John's authority as a ruling monarch. He renounced it as soon as the barons left London; Pope Innocent III also annulled the "shameful and demeaning agreement, forced upon the King by violence and fear." The pope rejected any call for restraints on the king, saying it impaired John's dignity. He saw the charter as an affront to the church's authority over the king and the "papal territories" of England and Ireland, and he released John from his oath to obey it. The rebels knew that King John could never be restrained by Magna Carta, and so they sought a new King.

The First Barons' War

With the failure of the Magna Carta to achieve peace or restrain John, the barons reverted to the more traditional type of rebellion by trying to replace the monarch they disliked with an alternative. In a measure of some desperation, despite the tenuousness of his claim and despite the fact that he was French, they offered the crown of England to Prince Louis of France, who was proclaimed king in London in May 1216. John travelled around the country to oppose the rebel forces, directing, among other operations, a two-month siege of the rebel-held Rochester Castle. He died of dysentery contracted whilst on campaign in eastern England during late 1216; supporters of his son Henry III went on to achieve victory over Louis and the rebel barons the following year.

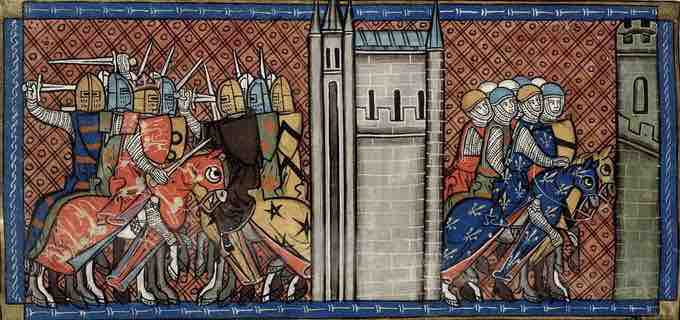

John of England vs Louis VIII of France

Created in the 14th Century; the image King John of England in battle with the Francs (left), Prince Louis VIII of France on the march (right).

Legacy

As a means of preventing war, the Magna Carta was a failure, rejected by most of the barons, and was legally valid for no more than three months. In practice, the Magna Carta did not generally limit the power of kings in the medieval period, but by the time of the English Civil War it had become an important symbol for those who wished to show that the king was bound by the law. The charter is widely known throughout the English-speaking world as having influenced common and constitutional law, as well as political representation and the development of parliament. The text's association with ideals of democracy, limitation of power, equality, and freedom under law led to the rule of constitutional law in England and beyond. It influenced the early settlers in New England and inspired later constitutional documents, including the Constitution of the United States.

John of England signs the Magna Carta

John of England signs the Magna Carta. Image from Cassell's History of England, Century Edition, published c. 1902. This image depicts the stress under the king and all those in England struggling for power.