West Virginia Opioid Prescribing For Chronic Pain While Avoiding Drug Diversion

- Article Author:

- Alexander Dydyk

- Article Author:

- Daniel Sizemore

- Article Author:

- Lindsay Trachsel

- Article Author:

- Till Conermann

- Article Editor:

- Burdett Porter

- Updated:

- 11/6/2020 6:54:27 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- West Virginia Opioid Prescribing For Chronic Pain While Avoiding Drug Diversion CME

- PubMed Link:

- West Virginia Opioid Prescribing For Chronic Pain While Avoiding Drug Diversion

Introduction

Chronic pain and opioid use and abuse is a significant problem in the United States.[1] Over one-quarter of United States citizens suffer from chronic pain.[2] It is among the most common complaints seen in an outpatient clinic and in the emergency department. The failure to manage chronic pain, as well as the possible complication of opioid dependence related to treatment, can result in significant morbidity and mortality. One in five patient complaints in an outpatient clinic is related to pain, with over half of all patients seeing their primary care provider for one pain complaint or another. It is paramount that providers have a firm grasp on the management of patients with chronic pain. As a country, the United States spends well over 100 billion dollars a year on healthcare costs related to pain management and opioid dependence.[3] Pain-related expenses exceed those for the costs of cancer, diabetes, and heart disease combined.[4] How a patient's chronic pain gets managed can have profound and long-lasting effects on a patient's quality of life.

The International Association for the Study of Pain defines chronic pain as any pain lasting longer than three months.[5] There are multiple sources of chronic pain. Combination therapy for pain includes both pharmacological therapies and nonpharmacological treatment options. There is a more significant reduction in pain with combination therapy compared to a single treatment alone. Escalation of pharmacological therapy is in a stepwise approach. Comorbid depression and anxiety are widespread in patients with chronic pain. Patients with chronic pain are also at increased risk for suicide. Chronic pain can impact every facet of a patient's life. Thus learning to diagnose and appropriately manage patients experiencing chronic pain is critical.[6]

Unfortunately, studies have revealed an inherent lack of education regarding pain management in most medical schools and training programs. The Association of American Medical Colleges recognized the problem and has encouraged schools to commit to opioid-related education and training by incorporating the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for prescribing opioids for chronic pain into the medical school curriculum.

Appropriate opioid prescribing includes prescribing sufficient opioid medication through regular assessment, treatment planning, and monitoring to provide effective pain control while avoiding addiction, abuse, overdose, diversion, and misuse. To be successful, clinicians must understand appropriate opioid prescribing, assessment, the potential for abuse and addiction, and potential psychological problems. Inappropriate opioid prescribing typically involves not prescribing, under prescribing, overprescribing, or continuing to prescribe opioids when they are no longer effective.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine describes addiction as a treatable chronic disease that involves environmental pressures, genetics, an individual's life experiences, and interactions among brain circuits. Individuals that become addicted to opioids or other medications often engage in behaviors that become compulsive and result in dangerous consequences. The American Society of Addiction Medicines notes that while the following should not be used as diagnostic criteria due to variability among addicted individuals, they identify five characteristics of addiction:

- Craving for drug or positive reward

- Dysfunctional emotional response

- Failure to recognize significant problems affecting behavior and relationships

- Inability to consistently abstain

- Impairment in control of behavior

Unfortunately, most health providers' understanding regarding addiction is often confusing, inaccurate, and inconsistent due to the broad range of perspectives of those dealing with patients suffering from addiction. While a knowledge gap is present among healthcare providers, it is equally prevalent in politicians writing laws and law enforcement attempting to enforce the laws they write. Payers are responsible for the expenses associated with the evaluation and treatment of addiction. Persistent lack of education and the use of obsolete terminology continue to contribute to a societal lack of understanding for effectively dealing with the challenges of addiction.

In the past, the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders defined "addiction," "substance abuse," and "substance dependence" separately. The result was provider confusion contributed to the under-treatment of pain. Over time, the manual has eliminated these terms and now uses "substance use disorder," ranging from mild to severe.

Unfortunately, there are numerous challenges in pain management, such as both underprescribing and overprescribing opioids. The concerns are particularly prominent in patients with chronic pain and have resulted in patients suffering from inadequately treated pain while at the same time there has been a development of concomitant opioid abuse, addiction, diversion, and overdose. As a result, providers are often negatively influenced and fail to deliver appropriate, effective, and safe opioids to patients with chronic pain. Providers have, in the past, been poorly trained and ill-informed in their opioid prescribing. To make the challenges even worse, chronic pain patients often develop opioid tolerance, significant psychological, behavioral, and emotional problems, including anxiety and depression related to under or overprescribing opioids.

Clinicians that prescribe opioids face challenges that involve medical negligence in either failure to provide adequate pain control or risk of licensure or even criminal charges if it is perceived they are involved in drug diversion or misuse. All providers that prescribe opioids need additional education and training to provide the best patient outcomes and avoid the social and legal entanglements associated with over and under prescribing opioids.

Provider Opioid Knowledge Deficit

There are substantial knowledge gaps around appropriate and inappropriate opioid prescribing, including deficits in understanding current research, legislation, and appropriate prescribing practices. Providers often have knowledge deficits that include:

- Understanding of addiction

- At-risk opioid addiction populations

- Prescription vs. non-prescription opioid addiction

- The belief that addiction and dependence on opioids is synonymous

- The belief that opioid addiction is a psychologic problem instead related to a chronic painful disease

With a long history of misunderstanding, poor society, provider education, and inconsistent laws, the prescription of opioids has resulted in significant societal challenges that will only resolve with significant education and training.

Etiology

Most patients who suffer from chronic pain complain of more than one type of pain.[7] For example, a patient with chronic back pain may also have fibromyalgia. A significant percentage of patients suffer from a major depressive and generalized anxiety disorder. Over 67% of patients with chronic pain suffer from a comorbid psychiatric disorder.[8]

There are multiple categories and etiologies of types of pain, which include neuropathic, nociceptive, musculoskeletal, inflammatory, psychogenic, and mechanical.[6][9]

Neuropathic Pain

- Peripheral neuropathic pain, as in the case of post-herpetic neuralgia or diabetic neuropathy

- Central neuropathic pain - cerebral vascular accident sequella

Nociceptive Pain

- Pain due to actual tissue injuries such as burns, bruises, sprains, or fractures.

Musculoskeletal Pain

- Back pain

- Myofascial pain

Inflammatory Pain

- Autoimmune disorders (rheumatoid arthritis)

- Infection

Psychogenic Pain

- Pain caused by psychologic factors such as headaches or abdominal pain caused by emotional, psychological, or behavioral factors

Mechanical Pain

- Expanding malignancy

Epidemiology

Chronic Pain

There are over 100 million people in the United States who would meet the criteria for chronic pain syndrome.[2] Over 50 million Americans suffer from debilitating chronic pain, and over 20 million indicate that pain interferes with their daily lives. Chronic regional pain is reported in 11.1 percent of chronic pain patients, while chronic back pain accounts for 10.1 percent, leg and foot pain 7.1 percent, arm and hand pain 4.1 percent, and headache 3.5 percent. There are reports of widespread pain in 3.6% of patients with chronic pain.[8] Elderly patients have been shown to receive up to 25% fewer pain medications than the average population.[10]

Chronic pain is estimated to cost over $600 billion annually in lost productivity and medical treatment. Lifetime chronic pain is common, with over 50% of adults being affected at some point in their lives. Over 40% of chronic pain patients indicated their pain is not controlled, and over 10% suffer long-term disabling chronic pain.

Research has shown the lifetime prevalence for chronic pain patients attempting suicide between 5% and 14%; suicidal ideation was approximately 20%.[11] Of the chronic patient patients who commit suicide, 53.6% died of firearm-related injuries, while 16.2% by opioid overdose.[12]

The incidence of chronic pain is increasing due to the prevalence of obesity-related pain conditions, increased survival of trauma and surgical patients, an aging population, and heightened public awareness of pain as a treatable condition.

Opioids

Opioids are the most used therapeutic agent for chronic pain and are derived synthetically from generally unrelated compounds. Opiates are derived from the liquid of the opium poppy either by direct refinement or by relatively minor chemical modifications. Both opioids and opiates act on three major classes of opioid receptors: mu, kappa, delta, and several minor classes of opioid receptors like nociceptin and zeta. Simplifying significantly, the mu receptors are thought to provide analgesia, respiratory suppression, bradycardia, physical dependence, gastrointestinal dysmotility, and euphoria. The kappa agonism can yield hallucinations, miosis, and dysphoria. The delta receptor likely has pain control and mood modulation effects, but some have suggested that mu agonism is necessary for the delta receptor to function strongly for analgesia.[13][14] The nociceptin receptor modulates brain dopamine levels and has clinical effects like analgesia and anxiolysis. The zeta receptor, also known as the opioid growth factor receptor, can modulate certain types of cell proliferation, such as skin growths, and are not thought to have many functions in modulating pain or emotion.[15][16]

In the past, providers in the United States rarely prescribed opioids for any condition except chronic cancer pain. This approach began to change in the 1990s. Dr. James Campbell addressed the American Pain Society (now bankrupt) in 1995 and urged healthcare providers to treat pain as the fifth vital sign.[17] The prescription of opioids for treating all chronic pain conditions has grown to the point that opioid sales have reached over 7 billion dollars. The United States currently consumes more than 80% of all opioids produced worldwide. With increased use, concomitant problems have developed, and the number of individuals abusing opioid analgesics has increased dramatically.[18][19]

West Virginia has been substantially affected by the diversion of prescription drugs, particularly hydrocodone and oxycodone. Hydrocodone and oxycodone are the most abused prescription drugs in West Virginia. With the education of providers on inappropriate prescribing of opioids and a slowing of diversion, individuals dependent on opioids have unfortunately shifted to the use of heroin and fentanyl. The death rate of overdose death due to prescription drugs has decreased while overdose deaths to non-prescription opioids have climbed rapidly. In fact, West Virginia has experienced the highest drug overdose rate in the country, with approximately 50 deaths per 100,000 population.[20]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of acute and chronic pain is complex and not completely understood. Research is ongoing. In general, the following provides an overview of the current understanding of pain pathophysiology.[6][9]

Acute Pain

It is caused by the activation of peripheral pain receptors and specific A-delta and C-sensory nerve fibers (nociceptors). It is commonly a response to tissue injury.

Chronic Pain

Chronic pain is usually related to ongoing tissue injury is thought to be caused by persistent activation of these pain fibers. Chronic pain may also develop from ongoing damage to or dysfunction of the peripheral or central nervous system which causes neuropathic pain.

Nociceptive Pain

Nociceptive pain receptors may be somatic or visceral. Somatic pain receptors are located in the subcutaneous tissues, fascia, connective tissues, endosteum, periosteum, joint capsules, and skin. Stimulation results in burning, dull, or sharp pain.

Visceral pain receptors are located in the viscera and connective tissue. Visceral pain due is usually due to obstruction of a hollow organ. This pain is deep, cramping, poorly localized, and may be referred to a remote site. Visceral pain from injury of connective tissue or organ capsules may be more localized and sharp.

Psychologic Factors

Psychologic factors in the modulation of pain intensity are highly variable. Culture, emotions, and thoughts and emotions affect an individual's perception of pain. Patients who suffer from chronic pain may also have psychological stress, particularly anxiety and depression. As a result of some syndromes being characterized as psychiatric disorders such as somatic symptom disorders defined by self-reported pain, patients are often mischaracterized as having a psychiatric disorder and are deprived of appropriate care. Pain may interfere with cognitive attention, concentration, the content of thought, and memory.

Multifactorial Pain Syndromes

Many pain syndromes are multifactorial; for example, cancer and chronic low back pain syndromes have a nociceptive component but may also involve neuropathic pain as a result of nerve damage.

Pain Modulation and Transmission

Pain fibers enter the spinal cord at the posterior root ganglia and synapse in the posterior horn. Fibers then cross to the contralateral side and travel up the lateral columns reaching the thalamus and, finally, the cerebral cortex. Repetitive stimulation from prolonged pain can sensitize neurons in the posterior horn of the spinal cord so that a minimal peripheral stimulus results in pain.

Peripheral and nerves at other levels of the central nervous system are sensitized, resulting in long-term synaptic changes in cortical receptive fields that can result in exaggerated pain perception. This process of chronic afferent input causing increased sensitivity and lower pain thresholds, with the remodeling of the central nociceptive pathways and receptors termed central sensitization. The consequence may be:

- Allodynia (exaggerated response to a nonpainful stimulus)

- Hyperalgesia (excessive pain response to a normal pain stimulus)

Substances Released When Tissue is Injured

The inflammatory cascade can sensitize peripheral nociceptors. Substances released include vasoactive peptides such as calcitonin, gene-related protein, neurokinin A, substance P, and mediators such as bradykinin and epinephrine prostaglandin E2, and serotonin. The pain signal is modulated in both segmental and descending pathways by neurochemical mediators such as endorphins (enkephalin) and monoamines (norepinephrine, serotonin). These mediators are thought to increase, reduce, shorten sustain the perception and response to pain. They also mediate the benefits of CNS-active drugs such as antidepressants, antiseizure drugs, membrane stabilizers, and opioids that interact with neurochemicals and specific receptors that treat chronic pain.

Psychologic factors are important pain modulators. They affect how patients describe and react to pain; such as complaining, being irritable, grimacing, or being stoic. They may also generate neural output that modulates neurotransmission along pain pathways. The psychologic reaction to protracted pain interacts with central nervous system factors that may induce long-term changes in pain perception.

Pain Theories

Intensity Theory

The theory goes back to the Athenian philosopher Plato (c. 428 to 347 B.C.) who, in his work Timaeus, defined pain not as a unique experience, but as an 'emotion' that occurs when the stimulus is intense and lasting. Centuries later, we are aware that especially chronic pain represents a dynamic experience, profoundly changeable in a spatial-temporal manner. A series of experiments, conducted during the nineteenth century, sought to establish the scientific basis of the theory. Based on the tactile stimulation and impulses of other nature, such as electrical stimulations, these investigations provided important information concerning the threshold for tactile perceptions and on the role of the dorsal horn neurons in the transmission/processing of pain.[21]

Cartesian Dualistic Theory

The oldest explanation for why pain manifested in specific populations was rooted in religious beliefs. Throughout history, religious ideologies have had a substantial influence on people’s thoughts and actions. As a result, the majority of people believed that pain was the consequence of committing immoral acts. There was also a belief that the suffering they endured was the individual’s way to repent for these sins.[9] Although this belief remained popular up until the nineteenth century, this was not due to the lack of other available theories. One of the first alternative scientific pain theories was bravely introduced in 1644 by the French philosopher Renee Descartes (1596-1650). This theory has the name in current literature as the Cartesian dualism theory of pain.[10]

The dualism theory of pain hypothesized that pain was a mutually exclusive phenomenon. Pain could be a result of physical injury or psychological injury. However, the two types of injury did not influence each other. At no point were they to combine and create a synergistic effect on pain, hence making pain a mutually exclusive entity.[11] In an attempt to placate the church, Descartes also included in his theory the idea that pain has a connection to the soul. He claimed that his research uncovered that the soul of pain was in the pineal gland, consequentially designating the brain as the moderator of painful sensations.[12]

The dualistic approach to pain theory fails to account for many factors that are known to contribute to pain today. Furthermore, it lacks explanation as to why no two chronic pain patients have the same experience with pain even if they had similar injuries. Despite these shortcomings, it still provided future researchers with a solid foundation to continue expanding the scientific understanding of the intricate phenomenon of pain.

Specificity Theory

Many scientists continued to do research long after Descartes proposed the dualistic theory of pain. However, it wasn’t until 1811 that another well-known pain theory came onto the scene. This theory, initially presented by Charles Bell (1774–1842), is referred to as the specificity theory. This theory is similar to Descartes' dualistic approach to pain in the way that it delineates different types of sensations to different pathways. In addition to the identification of specific pathways for different sensory inputs, Bell also postulated that the brain was not the homogenous object that Descartes believed it was, but instead a complex structure with various components.[13]

Scientists and philosophers alike spent the next century and a half further developing the specificity theory. One of the many contributors to this theory was Johannes Muller. In the mid-1800s, Muller published in Manual of Physiology that individual sensations resulted from specific energy experienced at certain receptors. Furthermore, Muller believed that there was an infinite number of receptors in the skin. This surplus of receptors accounted for the ability of an individual to discriminate between different sensations.[14] In 1894, Maximillian von Frey made another critical addition to the specificity theory that served to advance the concept: four separate somatosensory modalities found throughout the body. These sensations include cold, pain, heat, and touch.[15]

This concept correlates well with previous research done regarding this theory of pain, which served to reiterate the presence of distinct pathways for different sensations. Although this theory and the research surrounding it provided significant advancement to understanding pain, it still fails to account for factors other than those of physical nature that results in the sensation of pain. Much like the dualistic approach to pain, this theory also lacks an explanation for why sometimes pain persists long after the healing of the initial injury. This incomplete nature of the specificity theory regarding pain etiology necessitated additional theories and continued research.

Pattern Theory

Following the specificity theory, there were a handful of other philosophies introduced regarding the sensation of pain. Of these philosophies, the pattern theory of pain has the greatest coverage in the scientific literature. The American psychologist John Paul Nafe (1888-1970) presented this theory in 1929. The ideas contained with the pattern theory were directly opposite of the ideas suggested in the Specificity theory in regards to sensation. Nafe indicated that there are not separate receptors for each of the four sensory modalities. Instead, he suggested that each sensation relays a specific pattern or sequence of signals to the brain. The brain then takes this pattern and deciphers it. Depending on which pattern the brain reads, correlates with the sensation felt.[16] At the time of its introduction, the pattern theory gained significant popularity among many researchers. However, through further research and the discovery of unique receptors for each type of sensation, it can be stated with certainty that this theory is an inaccurate explanation for how we feel pain.

Gate Control Theory

In 1965, Patrick David Wall (1925–2001) and Ronald Melzack announced the first theory that viewed pain through a mind-body perspective. This theory became known as the gate control theory.[17] Melzack and Wall’s new theory partially supported both of the two previous theories of pain but also presented more knowledge to advance the understanding of pain further. The gate control theory of pain states that when a stimulus gets sent to the brain, it must first travel to three locations within the spinal cord. These include the cells within the substantia gelatinosa in the dorsal horn, the fibers in the dorsal column, and the transmission cells located in the dorsal horn.[18] The substantia gelatinosa of the spinal cord's dorsal horn serves to modulate the signals that get through, acting similar to a “gate” for information traveling to the brain.[19]

The sensation of pain that an individual feels is the result of the complex interaction among these three components of the spinal cord. Simply stated, when the “gate” closes, the brain does not receive the information that is coming from the periphery to the spinal cord. However, when the signal traveling to the spinal cord reaches a certain level of intensity, the “gate” opens. Once the gate is open, the signal can travel to the brain where it is processed, and the individual proceeds to feel pain. The information mentioned above accounts for the physical component of pain. Still, as stated earlier, the Gate Control Theory was one of the first to acknowledge that psychological factors contributed to pain as well. In their original study, Melzack and Wall suggested that in addition to the control provided by the substantia gelatinosa, there was an additional control mechanism located in cortical regions of the brain.[20]

In more recent times, researchers have postulated that these cortical control centers are responsible for the effects of cognitive and emotional factors on the pain experienced. Current research has also suggested that a negative state-of-mind serves to amplify the intensity of the signals sent to the brain as well.[21] For example, somebody who is depressed has a “gate” that is open more often, allowing more signals to get through, increasing the probability that an individual will experience pain from an otherwise normal stimulus. Also, there are reports that certain unhealthy lifestyle choices will also result in an “open gate,” which in turn leads to pain that is disproportionate to the stimulus.[22]

The gate control theory has proven to be one of the most significant contributions to the study of pain throughout history. The concepts that Melzack and Wall introduced to the study of pain are still utilized by researchers today. Even though this theory initiated the idea that pain wasn’t solely a result of physical injury but rather a complex experience, influenced by cognitive and emotional factors, additional research was necessary to comprehend the mechanisms and etiology of pain completely. This need precipitated the introduction of the following two philosophies regarding pain.

Neuromatrix Model

Almost thirty years after introducing the gate control theory of pain, Ronald Melzack introduced another model that contributed to the explanation of how and why people feel pain. Until the mid-1900s, most pain theories implied that this experience was exclusively due to an injury that had occurred somewhere in the body. The thinking was that if an individual suffered an injury, whether it be through trauma, infection, or disease, a signal would transmit to the brain, which would, in turn, result in the sensation of pain. Although Melzack had contributed to these previous theories, his exposure to amputees experiencing phantom limb pain in well-healed areas prompted his inquiry into this more accurate philosophy of pain. The theory he proposed is known as the neuromatrix model of pain. This philosophy suggests that it is the central nervous system that is responsible for eliciting painful sensations rather than the periphery.[23]

The neuromatrix model denotes that there are four components within the central nervous system responsible for creating pain. The four components are the “body-self neuromatrix, the cyclic processing, and synthesis of signals, the sentinel neural hub, and the activation of the neuromatrix.”[24] According to Melzack, the neuromatrix consists of multiple areas within the central nervous system that contribute to the signal, which allows for the feeling of pain. These areas include the spinal cord, brain stem and thalamus, limbic system, insular cortex, somatosensory cortex, motor cortex, and prefrontal cortex.[25] The signal that these areas of the central nervous system work together to create is responsible for allowing an individual to feel pain, and he referred to as the “neurosignature.” Furthermore, this theory states that input coming in from the periphery can initiate or influence the neurosignature, but these peripheral signals cannot create a neurosignature of their own.[26]

This idea that peripheral signals can alter the neurosignature is an important concept when considering the effect of nonphysical factors on an individual’s experience with pain. Melzack’s theory claimed that not only are there specific neurosignatures that elicit certain sensations but when there is an alteration in a certain signal, this allows for memory formation of these particular experiences. If the same circumstances occur again in the future, this memory allows for the same sensation to be felt.[27] In addition to the hypothesis that pain was a product of different patterns of signals from the central nervous system, the neuromatrix model continued to elaborate on the idea that was initially brought forward in the gate control theory, that pain can be affected not only by physical factors but by cognitive and emotional factors. Melzack suggested that hyperactivity of the stress response has a direct effect on pain. Hyperactivity of the stress response is when an individual exposed to increased levels of stress experiences a higher level of pain.[28]

Taking all of these claims into consideration, it is evident that pain is a complex issue that cannot be accounted for by physical factors alone. Even though the neuromatrix model further established the idea that cognitive and emotional factors influence pain in addition to physical factors, it still fails to account for social constructs of pain. Therefore, a new theory of pain must be utilized to appropriately explain the mechanism behind pain and why each individual’s experience with pain is unique.

Biopsychosocial Model

The biopsychosocial model provides the most comprehensive explanation behind the etiology of pain. This specific theory of pain hypothesizes that pain is the result of complex interactions between biological, psychological, and sociological factors. Any theory that fails to include all of these three pain constructs fails to provide an accurate explanation for why an individual is experiencing pain.[29] Although the term biopsychosocial was not introduced until 1954 by Roy Grinker (1900-1993), a neurologist and psychologist, many physicians had considered the utility of using such a model to approach the management of a patient’s pain long before this.[30]

One of the most prominent physicians who utilized this more comprehensive approach to pain was John Joseph Bonica (1917-1994). This Sicilian American anesthesiologist at Madigan Army Hospital established himself as the founding father of the pain medicine discipline. In the 1940s, Bonica cared for many patients who had returned home from World War II and were now experiencing debilitating pain due to injuries they had suffered in the war. He had recognized that the pain these wounded soldiers were experiencing was rather complex and not easily managed. This situation led him to propose that to adequately manage these patients, physicians needed to create interprofessional pain clinics comprising multiple disciplines.[31] At this moment in history, there was little support for the idea that pain was more than just the result of an injury, and Bonica was relatively unsuccessful in establishing these clinics. It wasn’t until 1977 that the biopsychosocial model was scientifically suggested as an explanation for the etiology of some medical conditions. George Engle claimed that to treat disease adequately; one must consider multidimensional concepts and manage the whole patient instead of focusing on a single issue.[32]

This methodology takes into account that the human body cannot be divided into separate categories when considering treatment options. Instead, it is beneficial to acknowledge the fact that illness and disease are the results of complex interactions between biological, psychological, and sociological factors, and they all affect an individual’s physical and mental well-being.[33] Although Bonica had technically been the first physician to comprehend the importance of using a biopsychosocial approach to pain, John D. Loeser, another anesthesiologist, has been credited as the first person to use this model in association with pain.[34]

Loeser suggested that four elements need to be taken into consideration when evaluating a patient with pain. These elements include nociception, pain, suffering, and pain behaviors. Nociception is the signal that is sent to the brain from the periphery to alert the body that there is some degree of injury or tissue damage. On the other hand, pain is the subjective experience that occurs after the brain has processed the nociceptive input. The last two components of pain that merit consideration is suffering and pain behaviors. The thinking is that suffering is an individual’s emotional response to the nociceptive signals and that pain behaviors are the actions that people carry out in response to the experience of pain. Both of these can be either conscious or subconscious.[35]

Loeser’s four pain elements account for the biological, psychological, and sociological factors that can create or influence an individual’s experience with pain. Failing to consider any one of these four elements when determining the cause or establishing a management plan could be a consideration as inadequate assessment or care. With a better understanding of what is causing a patient to experience pain, the doctor is provided with a more accurate foundation to begin formulating a treatment plan. Loeser’s findings prove that the Biopsychosocial Model of pain offers the most comprehensive philosophy and provides the framework that is needed to start appropriate therapy to manage patients with chronic pain adequately.

Histopathology

Chronic pain and opioids generally do not cause any specific histopathology in and of themselves. However, there is a diversity of histopathologic changes that can occur in the presence of improper/recreational parenteral administration of opioids. There may be chronic tissue damage present due to the original assault.[6]

Toxicokinetics

Opioids have an extensive diversity of durations and intensities of effect. For example, alfentanil has a half-life of around 1.5 hours; whereas, methadone has a half-life of between 8 to 60 hours. Opioid uptake and effect can also vary by administration route, some examples being fentanyl patches or long-acting oral formulations of oxycodone and morphine. Some, such as diphenoxylate and loperamide, have almost no effect other than suppression of bowel motility. Opioids such as methadone can significantly prolong the QT interval. Opioids can sometimes precipitate serotonin syndrome, especially when given to patients already taking various psychoactive medications (antidepressant medications like SSRI). There is an evolving body of knowledge that the intensity and quality of response to opioids can vary significantly between patients, which can be unrelated to tolerance; this is likely related to genetics, but this is not well characterized at this time.[22][19]

History and Physical

History

History should include the onset of pain, description, mechanism of injury if applicable, location, radiation of pain, quality, severity, factors contributing to relief or worsening of the pain, frequency of the pain, and any breakthrough pain. A verbal numeric rating scale (VNRS) or number scale for pain is a common measure to determine the severity of pain, numbered from 0 to 10. This tool is commonly used for pain intensity. Furthermore, associated symptoms should be assessed, such as muscle spasms or aches, temperature changes, restrictions to range of motion, morning stiffness, weakness, changes in muscle strength, changes in sensation, and hair, skin, or nail changes.

In addition to the patient's symptoms, the significance of the impact of the pain in day-to-day function should be discussed, and a review of daily living activities. It is important to understand how chronic pain affects the patient’s quality of life. Is pain impacting relationships or hobbies? Does the patient find themselves becoming depressed? Is the patient able to sleep throughout the night or exercise regularly? Can the patient go to work without limitations? Are activities of daily living affected, such as toileting, dressing, bathing, walking, or eating limited or restricted?

Older adults are a specific population that often identifies as suffering from chronic pain. The self-reporting of pain can be difficult in this population. Self-reporting of pain is essential for the identification and treatment of pain, while the inability to describe or communicate pain leads to undertreatment. Often elderly patients describe pain differently than the average population complicating diagnosis.[23][10] Instead of pain, an elderly patient may complain of soreness or discomfort.[24]

There are multiple acronyms used to obtain the history of a patient's pain. Some of the most commonly used abbreviations are "COLDERAS" and "OLDCARTS. These acronyms summarize the character, onset, location, duration exacerbating symptoms, relieving symptoms, radiation of pain, associated symptoms, and severity of illness. "PQRST" stands for provocation or palliation, quality, radiation or region, severity, and timing.[25]

A multidimensional assessment of a patient's pain and the severity of their pain can be completed. A Pain, Enjoyment, General Activity (PEG) tool can aid the multidimensional assessment of patients in pain.[26] The PEG score focuses on function and quality of life. A chronic pain patient who experiences daily 7/10 pain is treated with both pharmacological and nonpharmacological therapies. Following treatment, their pain is 5/10. A few points might not seem like a significant difference, but if their enjoyment and quality of life and function are improving, treatment may have had a profound impact on the patient's life. The PEG tool is scored 0 to 10 for each category. The higher the score, the worse the function and uncontrolled pain.

The Four-item Patient Health Questionnaire or PHQ-4 is a combination of the PHQ9 and GAD7 assessment tools used to evaluate depression and anxiety, respectively.[27] The PHQ-4 should be used as a screening tool for all cases of chronic pain. If the score of the PHQ-4 is more significant than five, then a full GAD-7, PHQ-9, and the Primary Care PTSD screening tools are recommended.[28]

The Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale (DVRPS) is a five-item tool with a 0 to 10 out pain scale, as well as an assessment of the impact of pain on sleep, mood, stress, and activity levels.[29]

In children's self-reporting, behavioral observation scales are used to assess pain.[30] Age-based rating scales of pain can be used. Visual analogs are also often implemented. Typically visual analogs are done with pictures of faces in various degrees of distress. By adolescence, children usually can rate their pain on a numerical scale, similar to adults.[31]

The Pediatric Pain Questionnaire and the Adolescent and Pediatric Pain Tool are used to assess the location of a patient's pain as well. The patient is asked to draw on the body map where they feel pain.[32] The ideal age for these tools is age 10 years.

Observational pain assessment tools are used in populations who cannot self-report. The facial expression, fussiness, distractibility, ability to be consoled, verbal responsiveness, and motor control are observational findings used in such an assessment tool. Observational pain assessment in infants or young children can use the (r-FLACC) tool.[30][33] The tool is an acronym for Revised Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability.[34][35] Multiple other validated tools can be used, the one that is better than another is the NAPI tool. However, multiple tools have been used and are validated.[36][37][38][33]

Nonverbal children with neurologic impairment (NI) is a challenging population to assess pain. Caregivers are often needed to help determine changes in the patient's behavior. Grimacing, moaning, increased muscle tone, crying, arching, atypical behavior such as aggressive behavior are a few symptoms to monitor in this population. Nonverbal children with NI include the Revised Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability (r-FLACC) scale, and the Individualized Numeric Rating Scale (INRS). The assessment adds specific behavior for atypical presentations.[34][37]

The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) can be used to assess patients' beliefs on pain and the impact of pain on their lives.[39][40] Separately, the McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ-2) includes a drawing for the location of pain on the human body, a questionnaire regarding previous pain medication use, and past experiences with pain.[41] Neuropathic pain is assessable using the Neuropathic Pain Scale to follow responses to therapy.

Physical

A detailed physical, including musculoskeletal, neurologic, and psychiatric exam, should be completed, as well as a focused examination of the area of pain.

Evaluation

Chronic Pain Assessment

Standard blood work and imaging are not indicated for chronic pain, but the clinician can order it when specific causes of pain are suspected. This can be on a case-by-case basis. In some cases, urine toxicology is ordered to monitor compliance and to exclude the use of nonprescription drugs.

Psychiatric disorders can amplify pain signaling making symptoms of pain worse.[42] Furthermore, comorbid psychiatric disorders, such as major depressive disorder, can significantly delay the diagnosis of pain disorders.[43] Major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder are the most common comorbid conditions related to chronic pain. There are twice as many prescriptions for opioids prescribed each year to patients with underlying pain and a comorbid psychiatric disorder compared to patients without such comorbidity.[24] Intuitively, this makes sense. For example, a patient suffering from depression often complain of fatigue, sleep changes, loss of appetite, and decreased activity. These symptoms can make their pain worse over time. It is also crucial to realize patients with chronic pain are at an increased risk for suicide and suicidal ideation.[11][12]

Simultaneously screening for depression is recommended for patients with chronic pain. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-II (MMPI-2) or Beck's Depression Scale are the two most commonly used tools. The MMPI-2 has been used more frequently for patients with chronic pain.[44][45]

Addiction Risk Assessment [18][46][47]

The clinician should consider information from the history and physical, family members, the state prescription monitoring program, and screening tools to assess the risk of developing an untoward behavioral response to opioids. Patients can be stratified to three risk levels:

- Low-risk: standard monitoring, vigilance, and care

- Objective signs and symptoms, localizable physical pathology

- Confirmatory testing such as physical exam findings, CT, MRI, etc.

- No individual or family history of substance abuse

- At most, mild medical or psychologic comorbidity

- Age < 45

- High pain tolerance

- Active coping strategies

- Willingness to participate in multimodal therapy

- Attempting to function at normal levels

- Moderate-risk: additional level of monitoring and more frequent provider contact

- Significant pain

- Defined pathology with objective signs and symptoms

- Confirmatory testing such as physical exam findings, CT, MRI, etc.

- Moderate psychologic problems controlled by therapy

- Moderate comorbidities well controlled by medical therapy and are not affected by opioids

- Mild opioid tolerance but not hyperalgesia without addiction or physical dependence

- Individual or family history of substance abuse

- Pain involving more than three regions of the body

- Moderate levels of pain acceptance

- Active coping strategies

- Willing to participate in multimodal therapy

- Attempting to function at normal levels

- High-risk: intensive and structured monitoring, frequent follow-up contact, consultation with addiction psychiatrist, and limited monthly prescription of short-acting opioids

- Significant widespread pain

- No objective signs and symptoms

- Pain involves more than 3 body regions

- Divergent drug-related behavior

- Individual or family history of addiction, dependency, diversion, hyperalgesia, substance abuse, or tolerance

- Major psychologic problems

- Age >45

- HIV-related pain

- High levels of pain exacerbation

- Poor coping strategies

- Unwilling to participate in multimodal therapy

- Not functioning at a normal lifestyle

Prescribing Opioids

Before prescribing opioids, complete a detailed patient history that includes:

- Indication requested for pain relief

- Location, nature, and intensity of pain

- Prior pain treatments and response

- Comorbid conditions

- Potential physical and psychologic pain impact on function

- Family support, employment, and housing

- Leisure activities, mood, sleep, substance use, and work

- Emotional, physical, or sexual abuse

When considering opioids, weigh the risks of abuse, addiction, adverse drug reactions, overdose, and physical dependence. If there are any special concerns, such as a history of substance abuse, consult a psychiatrist or addiction specialist. If current substance abuse, withhold prescribing until the patient is involved in an addiction treatment and monitoring program.

Assessment Tools [47]

Screening tools assist in determining risk level, and degree of monitoring and structure required for a treatment plan; however, their validity is not yet supported in the literature. Some examples of opioid tools include:

Brief Intervention Tool

Brief Intervention Tool is a 26-item "yes-no" questionnaire used to identify signs of opioid addiction or abuse. The items assess for problems related to drug use-related functional impairment.

CAGE, CAGE-AID, and CAGE-Opioid

CAGE (Cut down, Annoyed, Guilty, and Eye-opener) Questionnaire consists of four questions designed to assess alcohol abuse. CAGE-AID and CAGE-OPIOID are revised versions to assess the likelihood of current substance abuse.[48]

Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM)

The Current Opioid Misuse Measure is a 17-item patient self-report assessment designed to identify abuse in chronic pain patients. It identifies aberrant behaviors associated with opioid misuse in patients already receiving long-term opioid therapy.

Diagnosis, Intractability, Risk, and Efficacy (DIRE) Tool

The Diagnosis, Intractability, Risk, and Efficacy is a clinician-rated questionnaire used to predict patient compliance with long-term opioid therapy. Patients scoring low are poor candidates for long-term opioids.

Mental Health Screening Tool

The Mental Health Screening Tool is a five-item screen that evaluates feelings of calmness, depression, happiness, peacefulness, and nervousness in the past month. A low is an indicator that the patient should be referred to a pain management specialist.

Opioid Risk Tool

The Opioid Risk Tool is a five-item assessment to evaluate for aberrant drug-related behavior. It categorizes the patient into low, medium, or high levels of risk for aberrant drug-related behaviors based on question responses concerning previous alcohol, drug abuse, psychologic disorders, and other risk factors.

Pain Assessment and Documentation Tool (PADT)

Guidelines by the CDC, the Federation of State Medical Boards, and Joint Commission stress documentation from both a quality and medicolegal perspective. The Pain Assessment and Documentation Tool (PADT) was designed to help the clinician document appropriate information.

Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain-Revised (SOAPP-R)

The Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain-Revised (SOAPP-R) is a screen with questions addressing the history of alcohol or substance use, cravings, mood psychologic status, and stress. The SOAPP-R helps assess the risk level of aberrant drug-related behaviors and the monitoring level needed.

VIGIL

- Verification: Is this a responsible opioid user?

- Identification: Is the identity of this patient verifiable?

- Generalization: Do we agree on mutual responsibilities and expectations?

- Interpretation: Do I feel comfortable allowing this person to have controlled substances?

- Legalization: Am I acting legally and responsibly?

Urine Drug Tests (UDT)

Urine drug tests evaluate the use of the medication prescribed and detect unsanctioned drug use. The CDC recommends drug testing before starting opioid therapy and at least annually.

On study suggests monitoring frequency based on risk level.[49]

| Low-Risk Level | UDT every 1-2 years | State drug monitoring program - 2x per year |

| Medium-Risk Level | UDT every 6-12 months | State drug monitoring program - 3x per year |

| High-Risk Level | UDT every 3 months | State drug monitoring program - 4x per year |

Testing is usually done with class-specific immunoassay drug panels; however, this may be followed with gas chromatography/mass spectrometry for specific metabolite detection. The test should identify the specific drug. If urine test results suggest aberrant opioid use, discuss the issue in a positive, supportive approach, and document the discussion.

Treatment / Management

Healthcare professionals who treat patients with chronic pain should understand best practices in opioid prescribing, approaches to pain assessment, pain management modalities, and appropriate use of opioids for pain control. Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches should be evaluated. Patients with moderate-to-severe chronic pain who have been assessed and treated with non-opioid therapy without adequate pain relief are candidates for opioid therapy. Initial treatment should be a trial of therapy, not a definitive course of treatment. The CDC has issued updated guidance on the prescription of opioids for chronic pain. These guidelines address when to initiate or continue opioids for chronic pain; opioid selection, dosage, duration, follow-up, and discontinuation; and assessing risk and addressing opioid use harm.

Recommendations are to refer a patient to pain management in the case of debilitating pain, which is unresponsive to initial therapy. The pain may be located at multiple locations, requiring multimodal treatment or increases in dosages for adequate pain control or invasive procedures to control pain. Treatment of both pain and a comorbid psychiatric disorder leads to a more significant reduction of both pain and symptoms of the psychiatric disorder.[50] Pain may also worsen concurrent depression; thus, the treatment of pain has demonstrated to improve the responses to the treatments for depression.[51] There are multiple pharmacological, adjunct, nonpharmacological, and interventional treatments for chronic, severe, and persistent pain.

The list of pharmacological options for chronic pain is extensive. This list includes nonopioid analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, and aspirin. Additionally, medications such as tramadol, opioids, antiepileptic drugs (gabapentin or pregabalin) can be useful. Furthermore, antidepressants such as tricyclic antidepressants and SNRI’s, topical analgesics, muscle relaxers, N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists, and alpha 2 adrenergic agonists are also possible pharmacological therapies.

Treatment response can differ between individuals, but treatment is typically done in a stepwise fashion to reduce the duration and dosage of opioid analgesics. However, there is no singular approach appropriate for the treatment of pain in all patients.[52]

Chronic musculoskeletal pain is nociceptive pain. The treatment of such pain is in a stepwise approach but includes a combination of nonopioid analgesics, opioids, and nonpharmacological therapies. First-line therapy would be acetaminophen or NSAIDs. Both are effective for osteoarthritis and chronic back pain.[53][54][55] However, NSAIDs are relatively contraindicated in patients with a history of heart disease or myocardial infarction, renal disease, or patients on anticoagulation or with a history of ulcers.[56][57] There is limited evidence of which NSAID to use over another. One nonsteroidal antiinflammatory pharmacological agent may have a limited effect on a patient's pain while another may provide adequate pain relief. The recommendations are to try different agents before moving on to opioid analgesics.[58] Failure to achieve appropriate pain relief with either acetaminophen or NSAIDs can lead to considering opioid analgesic treatment.

Opioids are considered a second-line option; however, they may be warranted for pain management for patients with severe persistent pain or neuropathic pain secondary to malignancy.[59] There have been conflicting results on the use of opioids in neuropathic pain. However, for both short term and intermediate use, opioids are often used to treat neuropathic pain.[60] Opioid therapy should only start with extreme caution for patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain.[61] Side effects of opioids are significant and frequent and may include opioid-induced hyperalgesia, constipation, dependence, and sedation. For chronic musculoskeletal pain, they are not superior to nonopioid analgesics.[62][63]

Administration of opioid analgesics should be reserved for when alternative pain medications have not provided adequate pain relief or contraindicated and when pain is impacting the patient's quality of life. The potential benefits outweigh the short and long-term effects of opioid therapy. The patient must make an informed choice before starting opioid treatment after discussing the risks, benefits, and alternatives to opioids.[62][64][65] Patients taking opioids at greater than 100 morphine milligram equivalents per day are at significantly increased risk of side effects. Side effects of opioids such as respiratory compromise will increase as the dosages increase. Patients with chronic pain could benefit from a therapy program designed to wean them from opioid analgesics to a safer dosage.[66][67] Long-acting opioids should only be used over short-acting opioids in the setting of disabling pain, causing severe impairment to quality of life.[68]

There is an estimated 78 percent risk of an adverse reaction to opioids such as constipation or nausea, while there is a 7.5 percent risk of developing a severe adverse reaction ranging from immunosuppression to respiratory depression.[69] Patients with chronic pain who meet the criteria for the diagnosis of opioid use disorder should receive the option of buprenorphine to treat their chronic pain. Buprenorphine is a considerably better alternative for patients with very high daily morphine equivalents who have failed to achieve adequate analgesia.

Different types of pain also warrant different treatments. For example, chronic musculoskeletal back pain would be treated differently from severe diabetic neuropathy. A combination of multiple pharmacological therapies is often necessary to treat neuropathic pain. Less than 50% of patients with neuropathic pain will achieve adequate pain relief with a single agent.[70] Adjunctive topical therapy, such as lidocaine or capsaicin cream, can be utilized as well.[71][72]

The initial treatment of neuropathic is often with gabapentin or pregabalin. These are calcium channel alpha 2-delta ligands. They are indicated for postherpetic neuralgia, diabetic neuropathy, and mixed neuropathy.[73] There is limited evidence in the use of other antiepileptic medications to treat chronic pain, where many of these, such as lamotrigine, have a more significant side effect profile. The exception is carbamazepine in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia and other types of chronic neuropathic pain.[74][75]

Alternatively, antidepressants such as dual reuptake inhibitors of serotonin and norepinephrine (SNRI) or tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) can is an option. Antidepressants are beneficial in the treatment of neuropathic pain, central pain syndromes, and chronic musculoskeletal pain. For neuropathic pain, antidepressants have demonstrated a 50 percent reduction of pain. Fifty percent is a significant reduction, considering the average decrease in pain from various pain treatments is 30%.[76][77]

The serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) duloxetine is a useful treatment for treating chronic pain, osteoarthritis, and the treatment of fibromyalgia.[78] Furthermore, the efficacy of duloxetine in the treatment of comorbid depression is comparable to other antidepressants.[79][76] Venlafaxine is an effective treatment for neuropathic pain, as well.[80] A TCA can also be utilized, such as nortriptyline. TCA medications may require six to eight weeks to achieve its desired effect.[59]

Adjunctive topical agents such as topical lidocaine are a useful treatment for neuropathic pain and allodynia as in postherpetic neuralgia.[81][82] Topical NSAIDs have been shown to improve acute musculoskeletal pain, such as a strain, but are less effective in chronic pain. Yet, topical NSAIDs are more effective than controls in the treatment of pain related to knee osteoarthritis.[83][84] Separately, topical capsaicin cream is an option for chronic neuropathic or musculoskeletal pain unresponsive to other treatments.[85] Botulinum toxin has also demonstrated effectiveness in the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia.[86] The use of cannabis is also an area of interest in pain research. There is some evidence that medical marijuana can be an effective treatment of neuropathic pain, while the evidence is currently limited in treating other types of chronic pain.[87]

The list of nonpharmacological therapies for chronic pain is extensive. Nonpharmacological options include heat and cold therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, relaxation therapy, biofeedback, group counseling, ultrasound stimulation, acupuncture, aerobic exercise, chiropractic, physical therapy, osteopathic manipulative medicine, occupational therapy, and TENS units. Interventional techniques can also be utilized in the treatment of chronic pain. Spinal cord stimulation, epidural steroid injections, radiofrequency nerve ablations, botulinum toxin injections, nerve blocks, trigger point injections, and intrathecal pain pumps are some of the procedures and techniques commonly used to combat chronic pain. TENS units' efficacy has been variable, and the results of TENS units for chronic pain management are inconclusive.[88] Deep brain stimulation is for post-stroke and facial pain as well as severe, intractable pain where other treatments have failed.[89] There is limited evidence of interventional approaches to pain management. For refractory pain, implantable intrathecal delivery systems are an option for patients who have exhausted all other options.

Spinal cord stimulators are an option for patients with chronic pain who have failed other conservative approaches. Most commonly, spinal cord stimulators are placed following failed back surgery but can also be an option for other causes of chronic pain such as complex regional pain syndrome, painful peripheral vascular disease, intractable angina, painful diabetic neuropathy, and visceral abdominal and perineal pain.[90][91][92][93][94] Spinal cord stimulators have shown a 50% reduction of pain compared to continued medical therapy.[95]

Differential Diagnosis

Pain is a symptom, not a diagnosis. Developing a differential diagnosis for a patient's chronic pain is based on assessing the possible underlying etiologies of the patient's pain. It is essential to determine what underlying injury or disease processes are responsible for the patient's pain since this requires the identification of effective treatment. For instance, it is crucial to determine if a patient's neuropathic pain is peripheral or central. In another example, if a patient suffers from severe knee pain, it is essential to consider whether or not the knee pain is secondary to severe osteoarthritis since the patient may benefit from an injection or possibly from a knee replacement. In contrast, if the knee pain were instead related to a different condition such as rheumatoid arthritis, infection, gout, pseudogout, or meniscal injury, very different treatments would be necessary.

The differential diagnosis for generalized chronic pain would include patients who develop allodynia from chronic opioids as well as patients suffering from a major depressive disorder, as well as other psychiatric or sleep disorders, including insomnia. Furthermore, autoimmune diseases such as lupus or psoriatic arthritis, fibromyalgia as well as central pain syndromes, should be considered in states involving wide-spread, generalized chronic pain states. The four main categories of pain are neuropathic, musculoskeletal, mechanical, and inflammatory. Persistent and under-treated painful conditions can lead to chronic pain. Thus chronic pain is often a symptom of one or multiple diagnoses and can become its diagnosis as it becomes persistent and the body's neurochemistry changes. It is critical to treat acute and subacute pain before chronic pain develops.

Treatment Planning

Opioid therapy should begin as a trial for a pre-defined period, usually less than 30 days. Treatment goals should be established prior to the initiation of opioid therapy. These include the level of relief of pain, anxiety, depression, the return of function while avoiding unnecessary opioid use. The plan should include therapy selection, progress measures, and additional consultations, evaluations, referrals, and therapies. The provider should:

- Start at the lowest possible dose and then titrate to effect

- Start with short-acting opioid formulations

- Discuss the need for frequent risk/benefit assessments

- Be instructed in the signs and symptoms of respiratory depression

- Reassess risk/benefit with each dose increase

- Decisions to titrate dose to 90 mg or more morphine equivalent dose should be justified

- Be knowledgeable of federal and state opioid prescribing regulations

- Be knowledgeable of patient monitoring, equianalgesic dosing, and cross-tolerance with opioid conversion

- Augment treatment with nonopioid or, if necessary immediate-release opioids over long-acting opioids

- Taper opioid dose whenever possible

Consent and Treatment[18]

The opioid prescription should include documented informed consent and a treatment agreement addressing:

- Drug interactions

- Physical dependence

- Side effects

- Tolerance

- Physical dependence

- Driving and motor skill impairment

- Limited evidence of long-term benefit

- Addiction, dependence, misuse

- Risk/benefit profile of the drug prescribed

- Signs/symptoms of overdose

Prescribing policies should be clearly described, including policies regarding the number and frequency of refills and procedures for lost or stolen medications.

Patient and Physician treatment Agreement

- The patient should agree to use medications safely, avoid "doctor shopping," and to consent to urine drug testing

- The prescriber should agree to address problems, followup visits, and scheduled refills

Reasons for opioid therapy change or discontinuation should be listed. Agreements can also include follow-up visits, monitoring, and safe storage and disposal of unused drugs. If the patient does not speak English, an interpreter should be used.

Discontinuing Opioid Therapy

Discontinuing opioid therapy should be based on a physician-patient discussion. Opioids should be discontinued when the pain has resolved, side effects develop, analgesia is inadequate, or quality of life is not improved, deteriorating function, or there is evidence of aberrant medication use. Opioids should be tapered slowly, and withdrawal should be managed by an addiction specialist.

Toxicity and Side Effect Management

The American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians guidelines recommends monitoring for opioid adherence, abuse, and noncompliance by urine drug tests and monitoring programs.

The treatment plan for opioid use in chronic pain should include frequent assessment of pain level, origin, and function. If there is a change of dosage or agent, the frequency of patient visits should be increased. Chronic response to opioids should be monitored by evaluating the 5 A's.

- Affect

- Aberrant drug-related behaviors

- Activities of daily living

- Adverse or side effects

- Analgesia

Signs and symptoms, if present, that suggests treatment goals are not being achieved include:

- Decreased appetite

- Excessive sleeping or day/night reversal

- Impaired function

- Inability to concentrate

- Mood volatility

- Lack of involvement with others

- Lack of re-engaging in life

- Lack of hygiene

The decision to change, continue, or terminate opioid therapy is based on achieving treatment objectives without adverse effects. Physicians, wherever possible, should work with pharmacists.

Acute Overdose Management[19]

Accidental or deliberate overdose is always a risk factor in patients taking opioids. The patient and family should be instructed in the signs and symptoms of an overdose and basic emergency management until paramedics' arrival.

The immediate response to overdose management is to secure the airway and breathing; however, survival is heavily dependent upon the rapid administration of an opioid antagonist. Many states, including West Virginia, allow naloxone distribution to the public. Licensed healthcare providers may prescribe opioid antagonists for at-risk individuals, relatives, or caregivers. Emergency medical service personnel, peace officers, and firefighters also have the drug available.

While opioid antagonists such as naloxone, naltrexone, and nalmefene are available, acute overdoses are usually treated with naloxone as it quickly reverses opioid-related respiratory depression. Naloxone competes with opioids at receptor sites in the brain stem, reversing desensitization to carbon dioxide and preventing respiratory failure.

The naloxone dose is 0.4 to 2 mg administered intravenously, intramuscularly, or subcutaneously. The dose may be repeated every 2 to 3 minutes. Naloxone is available in pre-filled auto-injection devices. Advanced Cardiac Life Support protocols should be continued while naloxone is being administered.

In West Virginia, pharmacists and pharmacy interns may dispense naloxone without a provider prescription. The pharmacist or intern is required to screen the potential recipient by asking if they have a known hypersensitivity to naloxone; provide appropriate counseling and information on the product including dosing, effectiveness, adverse effects, storage, shelf-life, safety, and contact information (1-844-HELP-4-WV) for access to substance abuse treatment and recovery services if the recipient indicates interest in such services. Patients receiving opioid treatment for chronic pain may benefit from education and naloxone being available at home to treat an overdose.[96]

Prognosis

Current chronic pain treatments can result in an estimated 30% decrease in a patient's pain scores.[52] A thirty percent reduction in a patient's pain can have significant improvements to patients' function and quality of life.[97] However, the long-term prognosis for patients with chronic pain demonstrates reduced function and quality of life. Improved outcomes are possible in patients with chronic pain improves with the treatment of comorbid psychiatric illness. Chronic pain increases patient morbidity and mortality, as well as increases rates of chronic disease and obesity. Patients with chronic pain are also at a significantly increased risk for suicide compared to the regular population.

Spinal cord stimulation results in inadequate pain relief in about 50% of patients. Tolerance can also occur in up to 20 to 40 percent of patients. The effectiveness of the spinal cord stimulation decreases over time.[98] Similarly, patients who develop chronic pain and are dependent on opioids often build tolerance over time. As the amount of morphine milligram equivalents increases, the patient's morbidity and mortality also increase.

Ultimately, prevention is critical in the treatment of chronic pain. If acute and subacute pain receives appropriate treatment, and chronic pain can be avoided, the patient will have limited impacts on their quality of life.

Complications

Chronic pain leads to significantly decreased quality of life, reduced productivity, lost wages, worsening of chronic disease, and psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, and substance abuse disorders. Patients with chronic pain are also at a significantly increased risk for suicide and suicidal ideation.

Many medications often used to treat chronic pain have potential risks and side effects and possible complications associated with their use.

Acetaminophen is a standard pharmacological therapy for patients with chronic pain. It is taken either as a single agent or in combination with an opioid. The hepatotoxicity occurs with acetaminophen when exceeding four grams per day.[99] It is the most common cause of acute liver failure in the United States.[100] Furthermore, hepatotoxicity can occur at therapeutic doses for patients with chronic liver disease.[101]

Frequently used adjunct medications such as gabapentin or pregabalin can cause sedation, swelling, mood changes, confusion, and respiratory depression in older patients who require additional analgesics.[102] These agents require caution in elderly patients with painful diabetic neuropathy. Also, gabapentin or pregabalin, in combination with opioid analgesics, has been shown to increase the rate of patient mortality.[103]

Duloxetine can cause mood changes, headaches, nausea as well as other possible side effects, and should be avoided in patients with a history of kidney or liver disease.

Feared complications of opioid therapy include addiction as well as overdose resulting in respiratory compromise. However, opioid-induced hyperalgesia is also a significant concern. Patients become more sensitive to painful stimuli while on chronic opioids.[104] The long-term risks and side effects of opioids include constipation, tolerance, dependence, nausea, dyspepsia, arrhythmia (methadone treatment QT prolongation), and opioid-induced endocrine dysfunction, which can result in amenorrhea, impotence, gynecomastia, and decreased energy and libido. Also, there appears to be a dose-dependent risk of opioid overdose with increasing daily milligram morphine equivalents.

Complication rates for spinal could stimulators are high, ranging from five up to 40%.[105][106] Most commonly, lead migration occurs, causing inadequate pain relief, often requiring revision and anchoring.[107][108] Lead movement often occurs in the cervical region of the spinal cord, given an increased range of motion of the cervical vertebra.[109][110] Spinal cord stimulator lead fracture can occur in up to 9% of placements [111][112]. Seromas are also very common and may require surgical incision and drainage.[113][105] The risk of infection following a spinal cord stimulator placement is between 2.5 and 12 percent.[114][115] Lastly, direct spinal cord trauma could occur. The most significant infectious complication would be a spinal cord abscess. A dural puncture can cause a post-dural headache in up to 70% of patients.[116][117][113] The most significant adverse to spinal cord stimulator placement would be a spinal epidural hematoma. This emergency would require immediate neurosurgical decompression of the hematoma. The incidence of a spinal epidural hematoma is 0.71%.[118]

Drug Diversion and Drug Seeking[46]

Unfortunately, due to addiction or financial gain, some individuals seek prescribed opioids for illicit purposes. Prescription opioids may be obtained from a friend or relative, purchased from a black market drug dealer, obtained by doctor shopping and acquiring drugs from multiple prescribers, and theft from clinics, hospitals, or pharmacies.

- Aggressive demands for more opioids

- Asking for opioids by name

- Behaviors suggesting opioid use disorder

- Forged prescriptions

- Increased alcohol use

- Increasing medication dose without provider permission

- Injecting oral medications

- Obtaining medications from nonmedical sources

- Obtaining opioids from multiple providers

- Prescription loss or theft

- Reluctance to decrease opioid dosing

- Resisting medication change

- Requesting early refills

- Selling prescriptions

- Sharing or borrowing similar medications

- Stockpiling medications

- Unsanctioned dose escalation

- Using illegal drugs

- Using pain medications to treat other symptoms

Drug Diversion Interventions

Prescribers and dispensers can take several precautions to avoid drug diversion. Some approaches include:

- Communication among providers and pharmacies to avoid "doctor shopping"

- Educate patients on the dangers of sharing opioids

- Encourage patients to keep opioid medications in a private place

- Encourage patients to refrain from public disclosure of opioid use

- Report patient prescribing to state central database if available

If a patient is suspected of drug-seeking or diversion, consider the following actions:

Inquire about prescription and illicit drug use

- Obtain a urine drug screen

- Perform a thorough examination

- Perform pill counting

- Prescribe smaller quantities of the opioid

If a patient is abusing prescribed opioids, this is a violation of the treatment agreement. The provider may then chose to discharge the patient from their practice. If the relationship is terminated, the provider must do it legally. The provider should avoid patient abandonment, ending a relationship with a patient without consideration of continuity of care, and without providing notice to the patient. To avoid abandonment charges, the patient must be given enough advanced warning to allow them to secure another physician and facilitate the transfer of care

Patients with a substance abuse problem or addiction should be referred to a pain specialist. Theft or loss of controlled substances should be reported to the Drug Enforcement Administration. If drug diversion has occurred, the activity should be documented and reported to law enforcement.

Consultations

Seek consultation or patient referral when input from a pain specialist, addiction specialist, or psychiatrist is needed, particularly for long-term chronic pain management. Clinicians who prescribe opioids should be aware of opioid addiction treatment options.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Involvement of Patient and Family

The patient and family can assist in making informed decision-making regarding continuing or discontinuing opioid therapy. Family members are often aware of when a patient is depressed and less functional. Questions to ask the family include:

- Is the patient's day focused on taking opioid pain medication?

- What is the frequency of pain medication?

- Does the patient have any other alcohol or drug problems?

- Does the patient avoid activity?

- Is the patient depressed?

- Is the patient able to function?

What To Teach A Patient Taking Opioids

- Avoid driving or operating power equipment

- Avoid stoping opioids suddenly

- Avoid taking other drugs that depress the respiratory system as alcohol, sedatives, and anxiolytics

- Contact prescribing if pain medication is not adequate for relief

- Destroy opioids based on product-specific disposal information (usually flushing down the toilet or mixing with cat litter or coffee grounds)

- Do not chew tables

- Do not share opioids with friends or family

- Follow prescribed dosing regimen

- Provide product-specific information

- Take opioids only as prescribed

Pearls and Other Issues

Maintain Accurate Medical Records Regarding Opiate Prescriptions

All clinicians should maintain accurate, complete, and current medical records, including:

- Records of prescriptions for controlled substances

- Record instructions provided

- Detailed history, physical, monitoring, and reasons prescribed

Federal and State Laws[119]

Several regulations and programs at the federal and state level to reduce prescription opioid abuse, diversion, and overdose. These laws require:

- Immunity from prosecution for individuals seeking assistance during an overdose

- Pain clinic oversight

- Patient identification prior to dispencing

- Physical examination prior to prescribing opioids

- Prescription limits

- Prohibition from obtaining controlled substance prescriptions

- Tamper-resistant prescriptions

Federal Laws

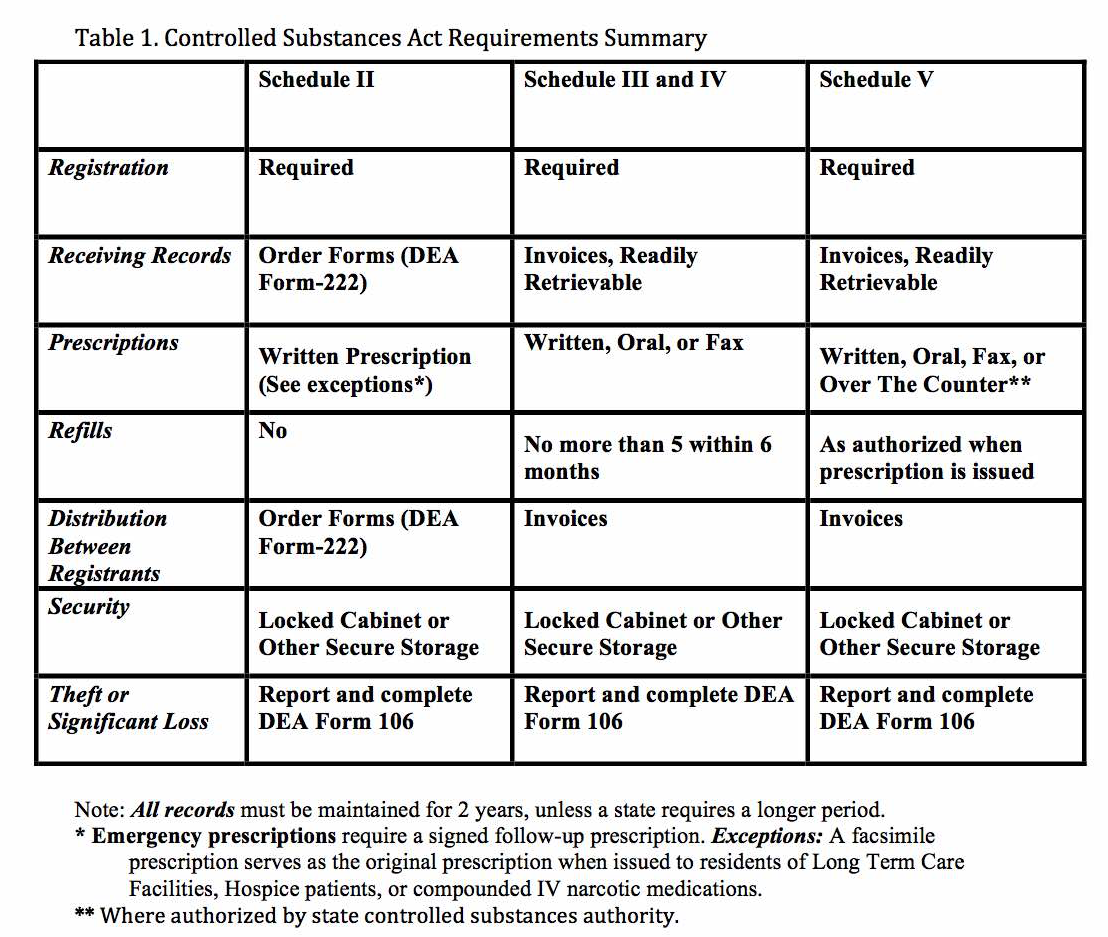

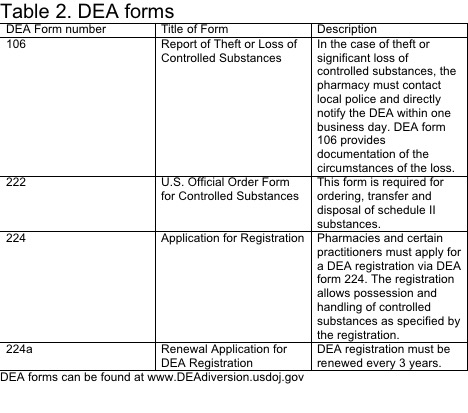

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) sets national standards for controlled substances. Drug scheduling was mandated under The Federal Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970. The law addresses controlled substances within Title II. The DEA maintains a list of controlled medications and illicit substances that are categorized from scheduled I to V. The five categories have their basis on the medication’s proper and beneficial medical use and the medication’s potential for dependency and abuse. The purpose of the law is to provide government oversight over the manufacturing and distribution of these types of substances. Prescribers and dispensers are required to have a DEA license to supply these drugs. The licensing provides links to users, prescribers, and distributors.[120][121][122]

The schedules range from Schedule I to V. Schedule I drugs are considered to have the highest risk of abuse while Schedule V drugs have the lowest potential for abuse. Other factors considered by the DEA include pharmacological effect, evidenced-based knowledge of the drug, risk to public health, trends in the use of the drug, and whether or not the drug has the potential to be made more dangerous with minor chemical modifications.

| Schedule | |

| I |