Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

- Article Author:

- Palma Shaw

- Article Author:

- John Loree

- Article Editor:

- Ryan Gibbons

- Updated:

- 8/10/2020 9:04:42 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm CME

- PubMed Link:

- Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a life-threatening condition which requires monitoring or treatment depending upon the size of the aneurysm and/or symptomatology. AAA may be detected incidentally or at the time of rupture. An arterial aneurysm is defined as a permanent localized dilatation of the vessel at least 150% compared to a relative normal adjacent diameter of that artery [1].

Etiology

Risk factors for AAA include advanced age, tobacco use, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and male gender. Atherosclerosis is the most commonly associated pathology, but other causes such as cystic medial necrosis, dissection, syphilis, HIV and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome have been identified.

Aneurysm enlargement can be step-wise with the stability of the size for some time and then a more rapid enlargement. Rate of enlargement for small AAA (3-5 cm) is 0.2 to 0.3 cm/year and 0.3 to 0.5 cm/year for those > 5 cm [2]. The pressure on the aortic wall follows the Law of Laplace (wall stress is proportional to the radius of the aneurysm). Because of this, larger aneurysms are at higher risk of rupture, and the presence of hypertension also increases this risk.

Epidemiology

Based on autopsy studies, the frequency of these aneurysms varies from 0.5% to 3%. The incidence of abdominal aortic aneurysms increases after age 60 and peaks in the seventh and eighth decades of life. White men have the highest risk of developing abdominal aortic aneurysms. They are uncommon in Asian, African American, and Hispanic individuals [3]. Data derived from Lifeline AAA screening and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES, 2003-2006)database reveals a prevalence of 1.4% or 1.1 million AAAs in those studied aged 50 to 84 [4]. With the increased use of ultrasound, the diagnosis of abdominal aortic aneurysms is quite common. They tend to be more common in smokers and elderly white males. Although autopsy studies may under-represent the incidence of AAA, one study from Malmo Sweden found a prevalence of 4.3% in men and 2.1% in women detected on ultrasound [5].

Pathophysiology

Abdominal aortic aneurysms tend to occur when there is a failure of the structural proteins of the aorta. What causes these proteins to fail is not known, but it results in the gradual weakening of the aortic wall. The decrease in structural proteins of the aortic wall such as elastin and collagen has been identified [6][7][8]. The composition of the aortic wall is made of collagen lamellar units. The number of lamellar units is lower in the infrarenal aorta than the thoracic aorta [8][9][10]. This is felt to contribute to the higher incidence of aneurysmal formation in the infrarenal aorta. A chronic inflammatory process in the wall of the aorta has been identified but is of unclear etiology [11].

Other factors that may play a role in the development of these aneurysms include genetics, marked inflammation, and proteolytic degradation of the connective tissue in the aortic wall [12][13][14].

More than 90% of abdominal aortic aneurysms are fusiform.

Histopathology

Autopsy studies usually show marked degeneration of the media. Examination of resected abdominal aortic aneurysms usually reveals a state of chronic inflammation with an infiltrate of neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes. The media is often thin, and there is evidence of degeneration of the connective tissue.

History and Physical

The majority of abdominal aortic aneurysms are identified incidentally during an examination for another unrelated pathology. Most individuals are asymptomatic. Palpation of the abdomen usually reveals a pulsatile abdominal mass which is not tender. Enlarging aneurysms can cause symptoms of abdominal, flank or back pain. Compression of adjacent viscera can cause gastrointestinal (GI) or renal manifestations. Rupture of an abdominal aortic aneurysm is life-threatening. These patients may present in shock often with diffuse abdominal pain and distension. However, the presentation of patients with this type of ruptured aneurysm can vary from subtle to quite dramatic. Most patients with a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm die before hospital arrival. On physical exam, the patient may have tenderness over the aneurysm or demonstrate signs of embolization. The aneurysm may rupture into adjacent viscera or vessels presenting with GI bleeding or congestive heart failure due to the aortocaval fistula. Physical exam should also look for other associated aneurysms. The most common associated aneurysm is an iliac artery aneurysm. Peripheral aneurysms are also associated in approximately 5 % of patients, of which popliteal artery aneurysms are the most common.

Evaluation

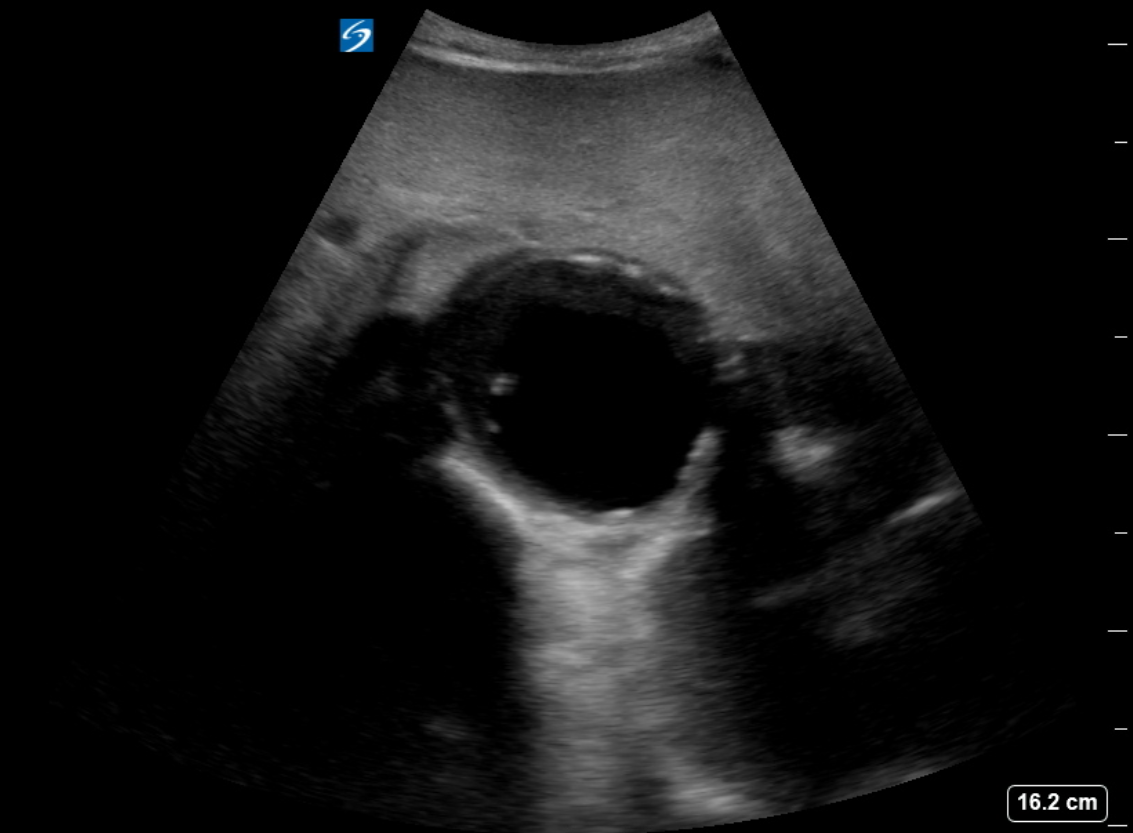

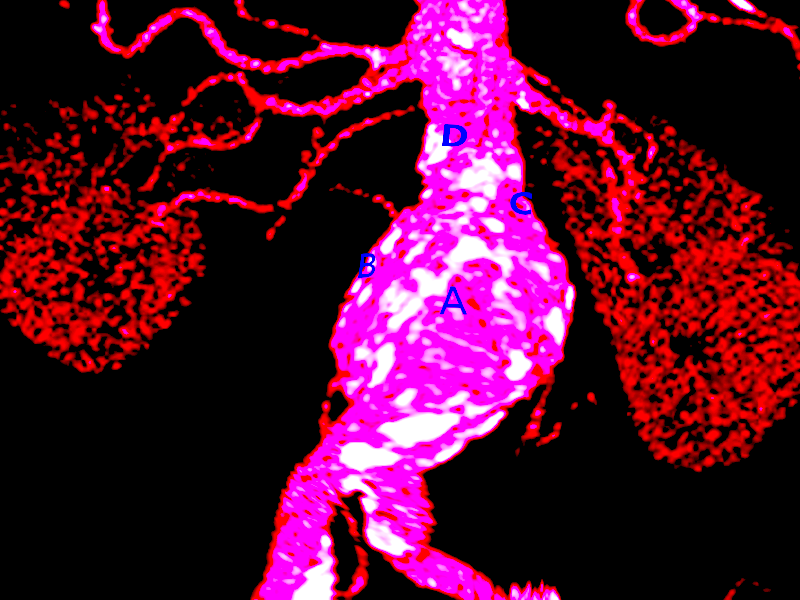

The diagnosis of an abdominal aortic aneurysm is usually made with ultrasound (US), but a CT scan is needed to determine the exact location, size, and involvement of other vessels. The US can be used for screening purposes but is less accurate for aneurysms above the renal arteries because of the overlying air-containing lung and viscera. CTA requires the use of ionizing radiation and intravenous contrast. Magnetic resonance angiography can be used as well to delineate the anatomy and does not require ionizing radiation.

Most of these aneurysms are located below the origin of the renal arteries. They may be classified as saccular (localized) or fusiform (circumferential). Some people may develop an inflammatory abdominal aortic aneurysm which is characterized by intense inflammation, a thickened peel, and adhesions to adjacent structures. Angiography is now rarely done to make the diagnosis because of the superior images obtained with CT scans [15].

For those patients with allergies to contrast, MRA is an option. An echocardiogram is recommended as many patients also tend to have associated heart disease.

If surgery is necessary, all patients need routine blood work including a cross match. Patients with comorbidity like diabetes, COPD or heart disease should be seen by the relevant specialist and cleared for surgery.

Treatment / Management

The treatment of unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm has changed over time. Treatment is recommended when it reaches 5 cm to 5.5 cm, is demonstrated as rapidly enlarging > 0.5 cm over 6 months or becomes symptomatic. Open surgical repair via transabdominal or retroperitoneal approach has been the gold standard. Endovascular repair from a femoral arterial approach is now applied for a majority of repairs, especially in older and higher risk patients. Endovascular therapy is recommended in patients who are not candidates for open surgery. This includes patients with severe heart disease, and/or other comorbidities that preclude open repair. A ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm warrants emergency repair. Endovascular approach for ruptured AAA has demonstrated superior results and survival compared to open repair if the anatomy is suitable, but the mortality rates remain high. The risk of surgery is influenced by the age of the patient, the presence of renal failure, and the status of the cardiopulmonary system [16][17].

Data show that for unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms, endovascular repair has no long-term differences in outcomes compared to open repair. However, there are also data which indicates that expansion of the neck of the aorta continues despite endovascular therapy, and this is of concern. The need to take beta blockers cannot be understated in these patients. An open repair has been the gold standard for AAA repair for many decades. It involves a long midline incision followed by replaced of the diseased aorta with a graft. Postoperatively, these patients do need close monitoring in the ICU for 24-48 hours.

All patients with small abdominal aortic aneurysms who do not undergo repair need periodic follow up with an ultrasound every 6 to 12 months to ensure that the aneurysm is not expanding[18].

SVS Guidelines on Management of Patients With Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms

The Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) issued updated guidelines on the care of patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms that include the following:

- Yearly surveillance imaging in patients with an AAA of 4.0 to 4.9 cm in diameter.

- Assessment of distal leg pulses at each clinic visit.

- For unruptured AAA, endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) is recommended.

- Endovascular procedure should only be done in a hospital that has performed at least 10 cases every year and has a conversion rate to open of less than 2%

- Elective AAA open surgery should be done in hospitals with a mortality of less than 5% and that performs at least 10 open cases a year

- For ruptured AAA, a facility with door to intervention time of less than 90 minutes is preferred.

- Recommend treatment of type I and III endoleaks as well as of type II endoleaks with aneurysm expansion.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended before respiratory tract procedures, genitourinary, dermatologic, gastrointestinal or orthopedic procedures unless there is a potential for infection as in an immunocompromised patient.

- Color duplex ultrasonography should be used for postoperative surveillance after Endovascular surgery.

- A preoperative 12-lead electrocardiogram is recommended in all patients undergoing EVAR or open surgical repair within 4 weeks of the elective surgery.

- If the patient just had a drug-eluting stent placed, then open aneurysm surgery should be delayed for at least 6 months; or one can perform endovascular surgery while the patient is on dual antiplatelet therapy.

- Only transfuse blood perioperatively if hemoglobin is less than 7 g/dL.

- Elective repair should be recommended in patients at low risk when the AAA is 5.5 cm.

- The open surgery should be done under general anesthesia.

Differential Diagnosis

- Mesenteric ischemia

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Renal calculi

- Diverticulitis

- Pyelonephritis

Prognosis

Once an abdominal aortic aneurysm ruptures, the prognosis is grim. More than 50% of patients die before they reach the emergency room. Those who survive have very high morbidity. Predictors of mortality include preoperative cardiac arrest, age >80, female gender, massive blood loss and ongoing transfusion [19]. In a patient with a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, the one factor that determines mortality is the ability to get proximal control. For those undergoing elective repair, the prognosis is good to excellent. However, long-term survival depends on other comorbidities like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, and peripheral vascular disease. It is estimated that 70% of patients after repair will survive for 5 years.

Complications

- Bleeding

- Limb ischemia

- Delayed rupture secondary to endoleak

- Abdominal compartment syndrome

- Myocardial infarction

- Pneumonia

- Graft infection

- Colon ischemia

- Renal failure

- Bowel obstruction

- Blue toe syndrome

- Amputation

- Impotence

- Lymphocele

- Death

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

After repair, it is essential that the patient discontinue smoking, eat a healthy diet, and maintain a healthy weight. Physical and/or occupational therapy may be necessary.

Consultations

Once an abdominal aortic aneurysm is diagnosed, the patient should be referred to a vascular surgeon. Surveillance imaging at 12-month intervals is recommended or patients with an AAA of 4.0 to 4.9 cm in diameter [20].

To ensure that the patient is fit for surgery, cardiology and pulmonology as indicated is recommended.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms should quit smoking is to reduce the risk of enlargement.

- Medical optimization of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and other atherosclerotic risk factors.

- Moderate exercise does not cause rupture or AAA expansion [21].

- The Society for Vascular Surgery Guidelines recommends ultrasound screening for all men and woman 65 years of age or older who have smoked or have a family history of AAA(20).

- Surveillance Guidelines for AAA per the Society for Vascular Surgery using duplex US are the following:

- 3-year intervals for patients with an AAA between 3.0 and 3.9 cm

- 12-month intervals for patients with an AAA of 4.0 to 4.9 cm in diameter.

- 6-month intervals for patients with an AAA between 5.0 and 5.4 cm in diameter

- Those patients with an initial aortic diameter <3 cm have a low risk for rupture. At this time there are no recommendations for surveillance; however, it should be noted that gradual expansion in these patients has been noted over time.

- Patients presenting with a symptomatic AAA should be considered for urgent repair.

- Asymptomatic patients with AAA demonstrating an aortic diameter > 5.4 cm or those with the rapid expansion of small AAA should be evaluated for repair.

- The goal of AAA repair is to increase survival. Consideration of quality of life after the repair is important; particularly in those with shortened life expectancy due to medical co-morbidities or cancer.

- Endovascular repair may offer fewer complications and better quality of life in those at high risk for open repair up to 1-year post-intervention [22].

Factors that increase the operative risk for abdominal aortic aneurysm repair include:

- Severe heart disease.

- Severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

- Poor renal function

- Comorbidities such as stroke, diabetes, hypertension, and advanced age can increase open surgical risk. These individuals should be considered for endovascular stenting of the aneurysm if the aortic anatomy permits.

Infrarenal Aortic Aneurysm Repair

Consideration for repair is appropriate for all symptomatic aneurysms. Aortic anatomy and device availability can dictate the approach. Open aneurysm repair had been the gold standard but carries increased risk and potential complications which may be acceptable in a younger good surgical risk patient. This is still the more durable procedure. Endovascular repair is now an established technique for repairing an abdominal aortic aneurysm. This minimally invasive procedure can also be offered but has better outcomes and durability when the anatomy meets device specific recommendations. This is the preferred approach in cases of rupture and in patients with multiple risk factors or shortened life expectancy. Intervention or surgical treatment risks versus benefits of repair in patients at increased risk for open surgery should be considered, and no intervention may be appropriate in some cases. Patients should be well informed regarding their options, risks of repair and potential post-operative complications. Endovascular repair requires life-long follow up with imaging as early, or late endoleaks may develop causing aortic sac pressurization and rupture. Secondary interventions may be necessary the majority of which are minimally invasive, but there is a small chance that open conversion with the removal of the stent graft may be required when these secondary endovascular interventions fail.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms are the most common aneurysms of the aorta. Screening ultrasound has helped detect AAA and allow for surveillance in asymptomatic patients with a diameter < 5 cm. In females, the repair should be considered at 5 cm and in males at 5.5 cm. If rapid enlargement is demonstrated (>5 mm over 6 months) repair should be considered. Education of first responders including the nurse practitioner, triage nurse, primary care physicians, physician assistants, and emergency department physicians can facilitate diagnosis and reduce delays in treatment.

An interprofessional team approach of emergency nurses, emergency physicians, intensivists, radiologists and a vascular surgeon will facilitate rapid evaluation and treatment and improve outcomes. The vast majority of patients with AAA initially present to the emergency department with vague abdominal pain and/or a pulsatile mass. Thus, the triage nurse must be familiar with the presentation of an AAA and initiate a rapid admission with direct communication to the emergency department physician and the rest of the interprofessional team about the patient. Once admitted, if stable these patients need an urgent ultrasound and hence the radiologist needs to be notified. If the patient is unstable, the nurse should obtain vitals, attach monitoring equipment, and assist with resuscitation if the patient is hemodynamically unstable. Referral to a vascular center that can provide a standard of care management is appropriate. Once the decision for repair has been made, cardiology workup and clearance and optimization of other medical co-morbidities can improve outcomes. If the aneurysm is small, the patient and family should be educated by the interprofessional team regarding compliance with blood pressure control, a healthy diet, exercise, cessation of smoking, and follow up.

During postoperative care, the nurse has to be familiar with potential complications of the surgery and notify the interprofessional team if the patient has abdominal or back pain, wound discharge, fever, oliguria or hypotension. The nurse should also ensure that the patient has prophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis prevention. The respiratory therapist has to encourage deep breathing and cough, and the physical therapist has to encourage ambulation. The nurse should also auscultate for bowel sounds and convey the results to the interprofessional team so that feeding can be initiated. Prior to discharge, the pharmacist and nurse should educate the patient on the importance of medication compliance, the need to control blood pressure and avoiding tobacco. The nurse should also ensure that the appropriate consulting physician/dietitian/social workers have seen the patient and the surgeon notified prior to discharge. Open communication between the interprofessional team is vital to ensure good outcomes.

Outcomes

For elective AAA repair, the outcomes are good with minimal morbidity. However, if a rupture has occurred, the mortality rates can exceed 50%. Current guidelines suggest that patients with AAA should have the surgery in hospitals with an interprofessional team approach in dealing with this pathology. To improve outcomes, it is vital that the patient stop smoking, maintain a healthy body weight, control his or her blood pressure, and remain compliant with medications.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Contributed by Meghan Herbst, MD