Neuroanatomy, Cranial Nerve 11 (Accessory)

- Article Author:

- Bruno Bordoni

- Article Author:

- Ryder Reed

- Article Author:

- Prasanna Tadi

- Article Editor:

- Matthew Varacallo

- Updated:

- 7/31/2020 3:18:07 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Neuroanatomy, Cranial Nerve 11 (Accessory) CME

- PubMed Link:

- Neuroanatomy, Cranial Nerve 11 (Accessory)

Introduction

The accessory spinal nerve or XI cranial nerve is essential for neck and shoulder movement, the intrinsic musculature of the larynx, and the sensitive afferences of the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid musculature. It can suffer an injury with daily movements or behaviors that exceed the elastic capacity of the nerve structure, such as excessive stretching or carrying heavyweights. These types of injuries are generally benign. The nerve may be seriously injured if the patient undergoes extensive tumor mass-removal surgery in the neck area, and there is a lack of blood nutrition or partial removal. When necessary, its removal becomes essential to compensate for a peripheral nerve lesion, transfer the cranial nerve where electrical activity is lacking, and efforts to restore limb function.[1][2]

Structure and Function

The ipsilateral activation of the XI nerve can activate the intrinsic laryngeal muscles fibers for the correct movement of the vocal cords of the same side. The main functions remain those of contracting the trapezius muscle and the sternocleidomastoid. According to recent research, the nerve not only has motor components but also sensitive components. Ganglions are found along its intracranial pathway with probable nociceptive function. These cell bodies could be involved in myalgias of the trapezius muscle and the sternocleidomastoid.

Anatomy

The accessory or spinal nerve has a double origin but always comes out of the jugular foramen. The jugular foramen develops embryologically from the otic capsule and the baseplate. Its spinal portion comes from a series of roots starting at C6-C7 and traveling cranially to enter in the foramen magnum. It then runs superolaterally along the floor of the posterior cranial fossa to enter in the dural canal of the jugular foramen, joining the small roots coming out of the medulla elongated caudally to the region of the ambiguous nucleus. From the jugular foramen, it comes out as nerve XI, together with X and IX, sigmoid sinus and the inferior petrosal sinus, while entering into jugular foramen the occipital and pharyngeal meningeal arteries. The nevus XI when it comes out of the jugular foramen is wrapped by the meningeal dura, which is attached to the periosteum. Once released, it separates into an internal and external branch: the internal branch is composed of fibers of the cranial part, giving an anastomosis with the vagus at the level of the upper edge of the transverse process of C1 and contributing to the vagal function of the pharyngeal and laryngeal area, transporting parasympathetic fibers; the outer branch mainly creates the fibers that will innervate the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles, which receive innervation also from C1-C4, that derive from the spinal portion and travel downwards.

It would seem that the cranial roots of the nerve are wider and in greater numbers on the right and for the male sex, but further data are expected. The external branch has a close relationship with the jugular vein, both in the jugular foramen and at the exit from the foramen at the cervical level, passing behind or in front or at the bifurcation.

According to current scientific literature, branches perforate the sternocleidomastoid and the trapezius muscle. It passes, with subjective anatomical variations, near an imaginary horizontal line from gonion towards the sternocleidomastoid, posterior to the edge of the muscle itself and about 4 to 9 centimeters below the apex of the mastoid process. Another point is located in the trapezius muscle, about 2 to 9 centimeters above the clavicula towards the acromion-clavicular joint.

According to Gray, there is another point, slightly below the first branch. To find the point, trace an imaginary, oblique line a few centimeters toward the caudality because the nerve has an oblique direction under the sternocleidomastoid.

An interesting anatomical note concerns the internal cranial area of the XI nerve before exiting the jugular foramen. The nerve rests on the vertebral artery entering and is also involved by the denticulated ligaments before exiting from the foramen. This means, on the one hand, that the vascular system (understood as the rigidity of the vessel) affects the function of the nerve and on the other side, that a traction of the cervical tract, both muscularly and vertebrally, can influence the nerve. A problem of deposits of calcium salts inside the vessel or of various vasculopathies that make the connective system of the vessel rigid and less able to adapt most likely will affect the elasticity of the nerve itself.

Likewise, for a previous traumatism of the high cervical tract, an incorrect postural attitude can disturb the function of the nerve. The number of fibers with myelin inside the cranial nerve XI can range from 1700 to 2000; the nerve diameter is about 2 millimeters.

Embryology

The embryological development of the XI nerve has the same origin as the vagus nerve, from the same ganglionic crest (ectoderm). The structure includes both motor components and sensitive components. As development progresses, its cranial termination becomes more sensitive, while its caudal termination acquires more motor functions.

At around 20 days, the ganglion crest is lateralized and divided into two portions (right and left); the caudal portion of the crest gives rise to a band of fibers, which will become the future accessory nerve. This band of fibers is located at the level of the fourth, fifth, and sixth cervical segment.

During the fourth week, it frees itself from the link of the vagus nerve to throw itself into a mesodermal mass, which will be the sternocleidomastoid muscle. At the end of the fifth week of gestation, the nerve is located medial to the dorsal rootlets and is connected at irregular intervals to what will be the spinal cord. It connects with the first spinal ganglion.

The cranial portion is a row of ganglia, found in the nerve once formed. The ganglia during development will be larger, forming a connection with the jugular ganglion of the vagus nerve.

During the second and third month, the XI nerve stretches and takes what will be its shape.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The intracranial portion of the nerve is vascularized from the proximal, distal, and recurrent branches of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery. The spinal roots of the nerve are affected by the musculospiral artery of the ascending pharyngeal artery and collaterals of the anterior spinal artery.

The extracranial portion is vascularized from the occipital artery and the branches of the lingual artery.

The extracranial path of the nerve, at the level of the posterior triangle of the neck, is followed by lymphatic nodes; the venous system follows the entire path of the nerve with small veins, affecting the external jugular vein.

Nerves

There is anastomosis between the accessory nerve and the root of C1 (but discordant texts also speak of C2-C3). An interesting anastomosis occurs with the stellate ganglion and the IX, although we do not know its function.

It also communicates with a branch of the big auricular nerve when it comes out of the jugular foramen. The XI has an anastomosis with the vagus (Lobstein anastomoses) at the level of the upper edge of the transverse process of C1.

Muscles

In its path, the XI nerve touches the elevator of the scapula and remains superficial to the prevertebral fascia. When it drops medially to the styloid process, it touches the stylohyoid muscle and the digastric muscles. The muscles innervated directly by the XI nerve are the trapezius and the sternocleidomastoid, in addition to the laryngeal musculature (in collaboration with the vagus nerve), such as the palatal, pharyngeal, laryngeal muscles.

Trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles have branchiomeric origin; the afferents that derive from these muscles reach the nucleus of the solitary tract. The trapezius muscle elevates, lowers, adduces and abducts, and externally rotates the scapula. It extends the head by rotating it to the opposite side. It extends, rotates, and tilts the head laterally. It participates indirectly in the flexion and abduction of the arm, raising the scapula from about 60 degrees upwards. The trapezius muscle is essential for a correct synergy between the shoulder, arm, and neck.

The contraction of only one side of the sternocleidomastoid muscle allows the flexion of the head from the contraction side and rotation of the head from the opposite side. The simultaneous contraction of the muscle produces the extension of the head.

The sternocleidomastoid also can have inspiratory muscle action by taking a fixed point on the temporal bone and then lifting the sternum and the clavicles.[3]

Physiologic Variants

The anatomy is a field full of surprises; nothing is ever definitive, in consideration of the knowledge to be acquired. Rich is the bibliography of anatomical dissections to demonstrate the many variations on the human body.

Root of C1

Four different patterns of intradural relationship exist between the XI nerve and the small roots of the first cervical nerve. In the first type, the posterior root of C1 is absent, whereas XI could anastomize with the anterior root of C1. In the second variant, there is no connection between XI and the posterior root of C1. In the third type of scheme, more anastomoses are found between XI and the posterior roots of C1 at different points. In the last type, there is a connection between XI and the posterior roots of C1, but without the connection to the spinal cord of the latter.

Other variations of the spinal accessory nerve path exist in relation to other neck structures.

Internal Jugular Vein

The nerve crosses the internal jugular vein ventrally, passes dorsally or laterally, or passes through the vein. Less frequently, it travels medially to the vein. Near the vein, the nerve XI could diverge and go back, traveling medially and laterally to the vein.

Sternocleidomastoid

- The XI passes along the internal surface of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) and sends branches without penetrating the muscle (type A); a single branch, without penetrating the muscle (type B), or penetrating the muscle deeply (type C).

- The trapezius muscle rarely could be innervated only by the cervical roots. Rarely, within the skull, the XI nerve could create an anastomosis with the facial nerve, innervating both the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

- The cervical plexus can contribute to the function of the spinal accessory nerve, from the level of C2 and C3.

Surgical Considerations

Iatrogenic Lesions

The path of the nerve is a sensitive area for the surgeon who must work in the area of the posterior triangle of the neck. The nerve is at risk for various iatrogenic lesions. One of these can be linked to the cannulation of the internal jugular vein with nerve palsy. Other iatrogenic causes refer to carotid endarterectomy, cardiac, or pulmonary surgery with sternotomy and radiation therapy. Some lesions can occur for lymphatic biopsies in the neck and thyroid surgery.[4][5][6]

Direct Pathologies

Direct pathologies to the XI nerve are rare but mainly involve a malfunction of the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid and can arise from cervical diseases in the foramen magnum and the jugular foramen and intracranial area.

Aneurysms to the internal carotid artery or posterior inferior cerebellar artery may cause permanent damage from ischemia to the nerve. A fracture of the atlas bone due to direct trauma could compress the nerve; a hyoid bone fracture may compress the nerve XI.

The following syndromes may negatively affect nerve function: Collet-Sicard-syndrome, Vernet-syndrome, Jugular-foramen-syndrome, Schmidt-syndrome, Villaret-syndrome, Garcin-syndrome, Pharyngo-cervical-brachial variant of Guillain-Barre-syndrome, Sandifer syndrome, Eagle-syndrome, Diphtheria (infection), Poliomyelitis or Tetanus (both situations that rarely can affect the XI nerve), botulism, and sarcoidosis. Other causes are diabetes, vitamin B12 deficiency, and tumors.

Nerve Transfer

The accessory nerve can be used in the procedures of neurotization and reinnervation of cervical plexus nerves, such as the radial, suprascapular, musculocutaneous, and axillary. You can use the nerve in patients with quadriplegia to replace the phrenic nerve.

Likewise, if the cranial nerve is subject to paralysis and permanent lesion, it can be replaced by the upper trunk of the brachial plexus, in particular, by fascicles of the upper trunk inherent in the axillary nerve.

Clinical Significance

During the clinical assessment for injury to CN XI (Spinal Accessory Nerve, SAN), the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid are assessed for strength and mass. The trapezius is assessed by asking the patient to shrug his or her shoulders with and without resistance, and the sternocleidomastoid is tested by asking the patient to turn his or her head to the left or right against resistance. Inspection of the muscles may reveal wasting or fasciculations.[7]

Trapezius muscle compromise or paralysis is most often is secondary to a neurogenic etiology as the SAN is vulnerable along its superficial course in the posterior triangle of the neck. Injury can occur secondary to blunt or direct trauma. Blunt trauma can cause injury during contact sports such as football or hockey. Penetrating trauma from either a gunshot wound, or penetrating deep laceration from sharp objects or weapons can also compromise the SAN.

It is easier to find a nuanced disorder secondary to repetitive traction injuries or compression neuropathy. If the clinician suspects scapular winging, abnormal/asymmetric neck rotational posturing, or atrophy of the trapezius muscle and shoulder pain and incapacity of shoulder abduction, scapular winging, it is worth evaluating the accessory nerve.

You can perform tests to analyze strength and reflexes. A small hammer is used in the clavicular area of insertion of the sternocleidomastoid to evoke its reflection.

The sternocleidomastoid strength is evaluated, by having the patient rotate his head from one side to the other while, overcoming the resistance posed by the operator. Similarly, to test the contractile trapezius reaction, the practitioner places his hands at the base of the patient's neck on the trapezius muscle, and the subject is asked to lift the shoulders.

Instrumental Evaluation

There are several options for investigating possible damage to the XI nerve. The use of X-ray (for the base of the skull and the styloid process), a video-cinematography, CT scan, magnetic resonance, angiography, and ultrasound. Electrophysiological procedures such as electromyography can be used to evaluate nerve function, electrical stimulation of spinal nerve roots, and transcranial magnetic stimulation.

Lateral Scapular Winging (LSW)

Trapezius muscle paralysis secondary to SAN injury causes the affected shoulder to droop and the scapular appearance is consistent with lateral winging. Compared to the normal side, the clinician should appreciate inferior translation of the scapula, and the inferior angle is rotated laterally. In subtle cases, the diagnosis can be elicited by asking the patient to push against the wall with his or her arms outstretched and the examiner can more readily observe these findings.

The workup for LSW begins with radiographs of the chest, c-spine, shoulder, and scapula. EMG/Nerve conduction studies are valuable adjuncts to confirm physical examination findings. Once confirmed, the clinician can serially monitor for SAN recovery in 3- to 6-month intervals.

Other Issues

Physiotherapy

Nerve rehabilitation should provide for the use of electrostimulation to the sternocleidomastoid and the trapezius muscles. Specific exercises to actively stimulate the muscles should be added as well as proprioceptive exercises.

Osteopathy

An osteopathic approach could improve the sliding of the tissues in the presence of scars. It could be useful to reduce the presence of pain or high levels of inflammation in the blood as studies show in other pathological conditions.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Meninges of the Dura mater, Dura mater and its processes, Straight sinus, Inferior Sagittal Sinus, Tentorium cerebelli, Transverse sinus, Great cerebral vein, Glossopharyngeal nerve, Vagus nerve, Accessory nerve, Acoustic nerve, Facial nerve, Abducens nerve, Trigeminal nerve, Trochlear nerve, Oculomotor nerve, Diaphragma sellae, Ophthalmic artery, Optic nerves, Olfactory tract

Contributed by Gray's Anatomy Plates

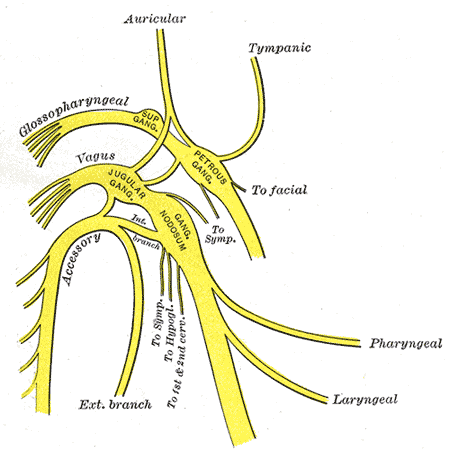

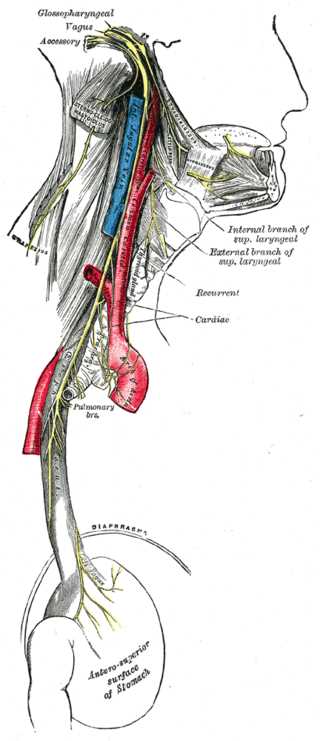

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)