Accessory Nerve Injury

- Article Author:

- Sanad AlShareef

- Article Editor:

- Bruce Newton

- Updated:

- 5/6/2020 9:30:31 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Accessory Nerve Injury CME

- PubMed Link:

- Accessory Nerve Injury

Introduction

The cranial nerves are twelve pairs of nerves that travel outside the skull via foramina to innervate various structures. Cranial nerve (CN) XI is also known as the accessory nerve. According to the morphology of the cranial root of the accessory nerve, it is made of the union of two to four short filaments, making the cranial roots of the accessory nerve then two to nine rootlets join the spinal root to form the nerve. The cranial roots of CN XI could be considered as part of the vagus nerve when factoring in the function of the two nerves. Both the cranial roots of the accessory nerve and the vagus nerve originate from nucleus ambiguus and dorsal nucleus of the vagus nerve and travel to the laryngeal muscles, supplying the motor fibers.[1] As the accessory nerve travels down and away from the brain, the cranial and spinal pieces of the nerve come together to form the spinal accessory nerve (SAN). The SAN is formed by the fusion of cranial and spinal contributions within the skull base and exits the skull through the jugular foramen adjacent to the vagus nerve.[2] The SAN descends alongside the internal jugular vein, coursing posterior to the styloid process, posterior belly of the digastric muscle, and sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) before entering the posterior cervical triangle. The accessory nerve leaves the jugular foramen along with the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX) and vagus nerve (CN X). It travels to the SCM, either superficial or deep, and then enters trapezius muscle, where a major trunk of the accessory nerve converges with C2, C3, or both. The traveling pathway of this nerve provides a functional significance to the structures in the posterior neck. However, the accessory nerve is prone to injury due to its long and superficial nature. Injury to the accessory nerve could be from blunt trauma, incidental, or, most commonly, iatrogenic reasons.[3]

Etiology

The most common cause for cranial nerve XI injury is iatrogenic, such as lymph node biopsies that involve the posterior triangle of the neck, neck surgeries including removal of a tumor, carotid or internal jugular vein surgeries, neck dissection (including radical, selective, and modified), or cosmetic surgery (e.g., facelift) from the mechanical stress exerted on the neck due to positioning throughout the procedure. Other causes are penetrating trauma such as knife or gunshot trauma, blunt trauma from pressure, stress to the neck area from a sudden movement, or acromioclavicular joint dislocation affecting SCM. Other possible sources of injury are neurological in which the nerve or the foramen it passes through are affected, leading to CN XI palsy. Examples are a tumor at the jugular foramen, which causes cranial nerve palsies such as Collet-Sicard syndrome, involving the cranial nerves IX, X, XI, and XII, and Vernet syndrome, involving the cranial nerves IX, X, and XI.[3] Syringomyelia, brachial neuritis, poliomyelitis, and motor neuron disease are other possible causes of CN XI injury. Other examples are traction palsies to brachial plexus and thoracic outlet.[4][5][6]

Epidemiology

Cranial nerve XI injuries most likely occur due to iatrogenic causes, such as posterior and lateral cervical triangle surgeries. The high likelihood of SAN injury with posterior and lateral neck surgeries led to exploring the various options with neck dissections such as radical, selective, and modified neck dissections in different studies. According to a retrospective study by Popovski et al., the SAN injury rate postoperatively is the highest, with radical neck dissections at 46.7% compared to selective neck dissections at 42.5% and 25% in modified neck dissections.[4][5][6][7] Other studies suggest the preservation of other structures such as the nerve, muscles, and veins would lead to fewer dysfunctions compared to more extensive procedures in the neck zones in which only the nerve is preserved. Although other causes of cranial nerve XI injury are uncommon, they are explored as part of the etiology.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of nerve injury depends on the etiology and mechanism of injury. Axonal injury is typically followed by Wallerian degeneration.

History and Physical

The most common and primary complaint of SAN injury is pain and weakness, mostly involving the shoulder. Radiation of pain is to the upper back, neck, and ipsilateral arm. Pain is exacerbated with weight on the injured shoulder without being supported. The traction and straining of the muscles rhomboids and levator scapulae that work to compensate for the nerve injury could lead to more pain and decreased strength on the injured side. The combination of the pain and decreased strength would limit the range of motion of the involved shoulder.[3]

The most common sign is the noticeable asymmetry on inspection of the shoulder and upper back. The patient would present with a diminished ability to hold the shoulder in abduction, shoulder drooping, and ipsilateral scapular winging (in which the medial side of the scapula is more prominent than the unaffected side). A limited active range of motion may eventually progress to a worsening of the passive range of motion, causing adhesive capsulitis. Other possible findings are atrophy of trapezius (depending on the length of time of the injury) and internal rotation of the humeral head.

Evaluation

Ultrasound, such as high-resolution ultrasonography (HRUS), has been used to confirm the target nerve and visualize the structures surrounding the nerve. Ultrasound helps detect some changes to the muscles, such as atrophy. It may also help reduce possible damage during the administration of injections and medication by guiding to correct targeted area while visualizing with ultrasound. Ultrasonography does not help detect the actual transection of the nerve.[2][8]

Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies are not needed for the diagnosis; however, it would be useful to distinguish and quantify the degree of damage by doing serial EMGs.

Electromyography (EMG) has shown that the trapezius is the main muscle responsible for shoulder elevation, and, by means of its upper bundle, it takes part in arm elevation. Nonetheless, this movement also involves the participation of the deltoid, supraspinatus, and infraspinatus muscles. For these reasons, certain spinal nerve mononeuropathy may be missed by healthcare providers because the movement may be compensated by the action of the other muscles responsible for arm elevation.[8]

Treatment / Management

The algorithm for management is divided between immediate therapy and delayed management. The severity and the cause of the SAN injury would be factors in determining whether the treatment is surgical, such as re-anastomosis and nerve grafting, or nonsurgical, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), nerve stimulation and local/ regional nerve blocking and physical therapy and rehabilitation. Immediate therapy should be considered for severe presentation, such as penetrating traumas and iatrogenic injuries.

Differential Diagnosis

- Long thoracic nerve injury causing paralysis or weakness of the serratus anterior muscle presents as winging of the scapula that is worse with lift-forward flexion of the arm or pushing the outstretched arm against a wall. This is different from CN XI injury, which has winging of the scapula with the abduction of the arm.

- Rotator cuff injury has a similar presentation when lifting the arm behind the head, except this injury does not present with winging of the scapula.

- Shoulder girdle arthritis and pain syndrome do not have muscular atrophy and winging of the scapula.

- Whiplash injury could cause neck pain and cervical spine rigidity and limited neck motion secondary to spasm and pain.

Prognosis

In a study in which half of the patients received primary nerve repair, and half of the patients received nerve graft, it was found that the recovery time ranged between 4 to 10 months.[9][10][11] However, one of the most important contributors to a better prognosis is an early referral, which leads to a more accurate diagnosis and appropriate intervention. Also, the early operative intervention has better results in regaining functionality; whereas, delayed diagnosis and treatment run the risk of less effective treatment and less predictable results.[9][12][13][14]

Complications

A patient with an injury to the SAN may present with neck pain, asymmetrical shoulders, inability to shrug the shoulder, or weakness in the neck area.

Deterrence and Patient Education

If the patient undergoes a surgical nerve repair, proper advice should be given on the restriction of motility and care of the wound. The importance of physiotherapy, when needed, should always be stressed.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

It is important for the nurse practitioner and primary care provider to refer any patient with an inability to shrug the shoulder or asymmetrical shoulders to a neurologist to determine the cause and treatment. Coordination of care for the patient is crucial, with physical therapy and occupational therapy playing a significant role in better recovery and improved outcomes.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Anterior Triangle, M. Mylohyoideus, Mandibula, M. Digastricus, Submental Triangle, Submandibular Triangle, Carotid Triangle, Muscular Triangle, M. Omohyoideus (venter superior), M. Sternocleidomastoideus, Processus Mastoideus, OS Hyoideum, M. Scalenus Medius, M. Scalenus Anterior, M. Omohyoideus (venter inferior), M. Trapezius, Clavicula

Contributed Illustration by Beckie Palmer

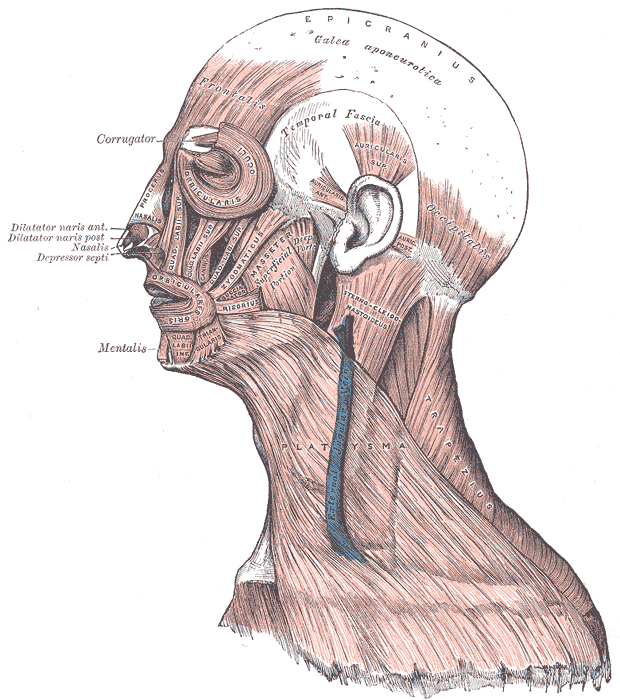

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Head Face and Neck Muscles, Epicranius, Galea aponeurotica, Frontalis, Temporal Fascia, Auricularis Superior, Auricularis Anterior, Auricularis Posterior, Occipitalis, Sternocleidomastoid, Platysma, Trapezius, Orbicularis Oculi, Corrugator, Procerus Nasalis, Dilatator Naris Anterior, Dilatator Naris Posterior, Depressor Septi, Mentalis, Orbicularis Oris, Masseter, Zygomaticus, Risorius

Contributed by Gray's Anatomy Plates

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Muscles connecting the upper extremity to the vertebral column, Occipital Bone, Superior Nuchal Line, Sternocleidomastoid, Ligamentum Nuchae, Splenius Capitis of Cervicis, Levator Scapula, Rhomboideus Minor and Major, Spine of Scapula, Trapezius, Deltoideus, Teres Major, Infraspinatus, Latissimus Dorsi, Serratus Posterior Inferior, Lumbar Triangle, Cres of Ilium, Sacral Vertebra

Contributed by Gray's Anatomy Plates

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Sinuses of Dura Mater, Falx cerebri, Tentorium cerebelli, Transverse sinus, Great cerebral vein, Glossopharyngeal nerve, Vagus nerve, Accessory nerve, Acoustic nerve, Facial nerve, Abducens nerve, Trigeminal nerve, Trochlear nerve, Oculomotor nerves, Diaphragma sellae, Ophthalmic artery, Optic nerves, Olfactory tract

Contributed by Gray's Anatomy Plates