Achilles Tendon Rupture

- Article Author:

- Alan Shamrock

- Article Editor:

- Matthew Varacallo

- Updated:

- 8/8/2020 9:02:30 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Achilles Tendon Rupture CME

- PubMed Link:

- Achilles Tendon Rupture

Introduction

Achilles tendon rupture is the most common tendon rupture in the lower extremity. The injury most commonly occurs in adults in their third to fifth decade of life. [1] Acute ruptures often present with sudden onset of pain associated with a "snapping" or audible "pop" heard at the site of injury. Patients can describe the sensation of being kicked in the lower leg. The injury is causes significant pain and disability in patient populations.

Achilles tendon injuries typically occur in individuals who are only active intermittently (i.e., the "weekend warrior" athletes). The injury is reportedly misdiagnosed as an ankle sprain in 20% to 25% of patients. Moreover, patients in their third to the fifth decade of life are most commonly affected as 10% report a history of prodromal symptoms, and known risk factors include prior intratendinous degeneration (i.e., tendinosis), fluoroquinolone use, steroid injections, and inflammatory arthritides.[2][3][4][5]

Etiology

Causes of Achilles tendon rupture include sudden forced plantar flexion of the foot, direct trauma, and long-standing tendinopathy or intratendinous degenerative conditions. Sports that are often associated with Achilles tendon rupture include diving, tennis, basketball, and track. Risk factors for a rupture of the Achilles tendon include poor conditioning before exercise, prolonged use of corticosteroids, overexertion, and the use of quinolone antibiotics. The Achilles tendon rupture usually tends to occur about two to four cm above the calcaneal insertion of the tendon. In individuals who are right-handed, the left Achilles tendon is most likely to rupture and vice versa.[6][7][8]

The exact cause of Achilles tendon injury appears to be multifactorial. The injury is most common in cyclists, runners, volleyball players, and gymnasts. When the ankle is subject to extreme pronation, it places enormous stress on the tendon, leading to injury. In cyclists, the combination of low saddle height and extreme dorsiflexion during pedaling may also be a factor in an overuse injury.

Systemic Factors

Systemic diseases that may be associated with Achilles tendon injuries include the following:

- Chronic renal failure

- Collagen deficiency

- Diabetes mellitus

- Gout

- Infections

- Lupus

- Parathyroid disorders

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Thyroid disorders

Foot problems that increase the risk of Achilles tendon injuries include the following:

- Cavus foot

- Insufficient gastrocsoleus flexibility and strength

- limited ability to perform ankle dorsiflexion

- Tibia vara

- Varus alignment with functional hyperpronation

It has been observed that Achilles tendon rupture is often more common in people with blood group O. Further anyone with a family history is also at a high risk of developing Achilles tendon rupture at some point in their life.

Epidemiology

The incidence rates of Achilles tendon ruptures varies in the literature, with recent studies reporting a rate of 18 patients per 100,000 patient population annually. In regard to athletic populations, the incidence rate of achilles tendon injuries ranges from 6% to 18%, and football players are the least likely to develop this problem compared to gymnasts and tennis players. It is believed that about a million athletes suffer from Achilles tendon injuries each year.

The true incidence of Achilles tendinosis is unknown, although reported incidence rates are 7% to 18% in runners, 9% in dancers, 5% in gymnasts, 2% in tennis players, and less than 1% in American football players. It is estimated that Achilles disorders affect approximately 1 million athletes per year.[9]

The incidence of Achilles tendon injuries is on the increase in the USA because of more participation of people into sporting activities. Outside the USA, the exact incidence of Achilles tendon injuries are not known, but studies from Denmark and Scotland reveal 6-37 cases per 100,000 persons.

Achilles tendon injuries appear to be more common in males, and this is probably related to greater participation in sports activities. Most injuries are seen in between the third and fifth decade of life. Many of these individuals are only active intermittently and rarely warm up.

Pathophysiology

Achilles tendonitis is often not associated with primary prostaglandin-mediated inflammation. It appears there is a neurogenic inflammation with the presence of calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P present. Histopathological studies reveal thickening and fibrin adhesions of the tendon with the occasional disarray of the fibers.

Neurovascularization is frequently seen in the degenerating tendon, which is also associated with pain. Tendon rupture is usually the terminal event during the degeneration process. After rupture, type 111 collagen appears to be the major collagen manufactured, suggesting that the repair process is incomplete. Animal studies show that if there is more than 8% stretching of their original length, tendon rupture is most likely.

The proximal segment of the tendon receives its blood from the muscle bellies connected to the tendon. Blood supply to the distal segment of the tendon is via the tendon-bone interface.

History and Physical

Patients often present with acute, sharp pain in the region of the Achilles tendon. On physical exam, patients with Achilles tendon rupture are unable to stand on their toes or have very weak plantar flexion of the ankle. Palpation may reveal a tendon discontinuity or signs of bruising around the posterior ankle.

The Thompson test is performed by the examiner to assess for achilles tendon continuity in the setting of suspected rupture. The examiner places the patient in the prone position with the ipsilateral knee flexed to about 90 degrees. The foot/ankle are in the resting position. Upon squeezing the calf, the examiner notes for the presence and degree of plantarflexion at the foot/ankle. This should be compared to the contralateral side. A positive (abnormal) test is strongly associated with achilles rupture.

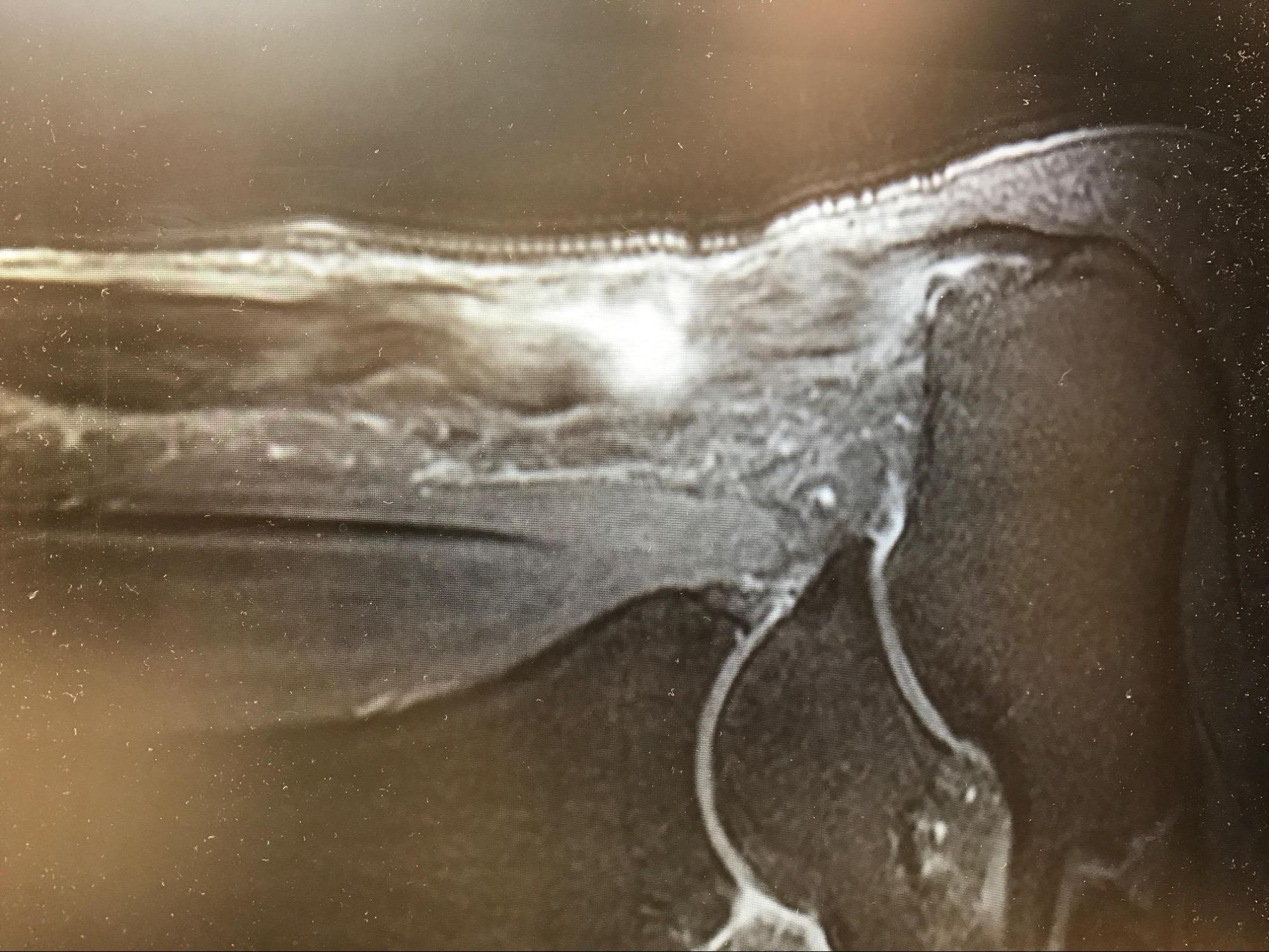

Evaluation

In the setting of trauma to the lower leg, radiographs are obtained to rule out the presence of a fracture. Based on clinical suspicion following the physical examination, the diagnosis can be confirmed with ultrasound or MRI. [10]

Treatment / Management

Operative Versus Nonoperative Management

The initial management of Achilles tendon rupture is rest, elevation, pain control, and functional bracing. There is still debate surrounding the potential benefits versus risks of surgical intervention. Studies have demonstrated good functional results and patient satisfaction with both operative and nonoperative modalities.

Healing rates with serial casting/functional bracing are no different compared to surgical anastomosis of the tendon, but return to work may be slightly prolonged in patients treated medically. All patients require physical and orthotic therapy to help strengthen the muscles and improve range of motion of the ankle.[11][4][12]

Rehabilitation is critical to regaining maximal ankle function. While the debate remains regarding the optimal treatment modality, the general consensus includes the following:

- Patients with significant medical comorbidities or those with relatively sedentary lifestyles are often recommended for nonoperative management

- Chronicity of the injury as well as soft tissue/skin integrity is also given consideration

- The patient/surgeon discussion should include a detailed discussion with respect to the current literature reporting satisfactory outcomes with both treatment plans, specifically

- Possiblity of quicker return to work with operative intervention

- Equivalent plantar flexion strength at long-term followup

- Possibility of an increased risk of re-rupture and/or re-injury with nonoperative management (compared to operative management)

- Lower complication rates for nonoperative treatment compared to operative management

There are several techniques for Achilles tendon repair, but all involve reapproximation of the torn ends. Sometimes the repair is reinforced by the plantaris tendon or the gastrocsoleus aponeurosis.

Overall, the healing rates between casting and surgical repair are similar. The debate about an early return to activity after surgery is now being questioned. If a cast is used, it should remain for at least 6-12 weeks. Benefits of a non-surgical approach include no hospital admission costs, no wound complications and no risk of anesthesia. The biggest disadvantage is a risk of re-rupture which is as high as 40%.

Differential Diagnosis

- Achilles bursitis

- Ankle fracture

- Ankle impingement syndrome

- Ankle osteoarthritis

- Ankle sprain

- Calf injuries

- Calcaneofibular ligament injury

- Calcaneus fractures

- Deep venous thrombosis (DVT)

- Exertional Compartment Syndrome

- Fascial tears

- Gastrocsoleus muscle strain or rupture

- Haglund deformity

- Plantaris tendon tear

- Psoriatic arthritis

- Reiter syndrome

- Retrocalcaneal bursitis

- Ruptured Baker cyst

- Syndesmosis

- Talofibular Ligament Injury

Prognosis

For most patients with Achilles tendon rupture, the prognosis is excellent. But in some non-athletes, there may be some residual deficits like a reduced range of motion.The majority of athletes are able to resume their previous sporting activity without any limitations. However, it is important to be aware that non-surgical treatment has a re-rupture rate of nearly 40% compared to only 0.5% for those treated surgically.

Complications

Re-rupture

- While newer level 1 evidence has reported no difference in re-rupture rates, prior studies have suggested a 10% to 40% re-rupture rate with nonoperative management (compared to 1% to 2% rate of re-rupture after surgery)

- Lantto et al. recently demonstrated in a randomized controlled trial of 60 patients from 2009 to 2013 at 18-month follow-up: [13]

- Similar achilles tendon performance scores

- Slightly increased calf muscle strength differences favoring the operative cohort (10% to 18% strength difference) at 18-month follow-up

- Slightly better health-related quality of life scores in the domains of physical functioning and bodily pain favoring the operative cohort

- Lantto et al. recently demonstrated in a randomized controlled trial of 60 patients from 2009 to 2013 at 18-month follow-up: [13]

Wound Healing Complications

- Overall, a 5-10% risk following surgery

- Risk factors for postoperative wound complications include:

- Smoking (most common and most significant risk factor)

- Female gender

- Steroid use

- Open technique (vs percutaneous procedures)

Sural Nerve Injury

- Increased rate of injury associated with the percutaneous procedure (compared to open technique)

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

No matter which method is used to treat the tendon rupture, participating in an exercise program is vital. One may swim, cycle, jog or walk to increase muscle strength and range of motion.

Deterrence and Patient Education

While active patients and recreational athletes often return to baseline activity levels and work following both nonoperative and operative management of these injuries, high-level professional athletes most often report inferior results and return to play regardless of the chosen management plan.

A 2017 study from the American Journal of Sports Medicine reported professional athletes followup performance (NBA, NFL, MLB, and NHL) at 1- and 2-year followup after surgery performed between 1989 and 2013: [14]

- >30% failure to return to play

- Athletes returning noted (at 1-year followup):

- Fewer games played, overall

- Less playing time, overall

- Suboptimal performance level, overall

- Athletes able to return to play, by 2-year followup:

- No statistically significant difference in performance level

Thus, athletes demonstrating the ability to return to play by 1-year should expect to achieve continued improvement to baseline performance by the ensuing season.

Pearls and Other Issues

To prevent rupture of the Achilles tendon, adequate warming and stretching before physical activity is recommended.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Even though there are several treatments for Achilles tendon rupture, there is no consensus on which one to undertake. There is a wide variation in the management of Achilles tendon injury between orthopedic surgeons and sports physicians. Further, there is no uniformity in postoperative rehabilitation. Experts recommend that an interprofessional approach may help achieve better outcomes. [10][15] (Level V) The team should include a trauma surgeon, orthopedic surgeon, rehabilitation specialist, and a sports physician. It is important that the pharmacist ensure that the patient is not on any medications that can affect the healing process. The nurse should educate the patient on the importance of stretching prior to any exercise and participating in a regular exercise program after repair.

Outcomes

Conservative treatment is usually preferred for non-athletes, but the risk of re-rupture is high. While surgery offers a lower risk of re-rupture, it is also associated with post-surgical complications that may delay recovery. Overall, the outcomes for Achilles tendon rupture are good to excellent after treatment.[16][17][18] (Level V)