Acoustic Neuroma

- Article Author:

- Joshua Greene

- Article Editor:

- Mohammed Al-Dhahir

- Updated:

- 8/10/2020 4:49:11 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Acoustic Neuroma CME

- PubMed Link:

- Acoustic Neuroma

Introduction

Acoustic neuroma is also called vestibular schwannoma (VS), acoustic neurinoma, vestibular neuroma or acoustic neurofibroma. These are tumors that evolve from the Schwann cell sheath and can be either intracranial or extra-axial. They usually occur adjacent to the cochlear and vestibular nerves and most often arise from the inferior division of the latter. Anatomically, acoustic neuroma tends to occupy the cerebellopontine angle. About 5-10% of cerebellopontine angle (CPA) tumors are meningiomas and may occur elsewhere in the brain. Bilateral acoustic neuromas tend to be exclusively found in individuals with type 2 neurofibromatosis.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Bilateral acoustic neuromas may be a part of neurofibromatosis type 2 occurring due to a defect on chromosome 22q12.2 at the location of the neurofibromin 2 gene which encodes merlin protein. Studies have shown that acoustic neuroma had a causative predisposition mutation. Radiation exposure may predispose a patient to the development of that condition as well.[4] Even though mobile phone radiation has been of concern, several studies have failed to prove its causative effect on vestibular schwannomas.[5]

Epidemiology

Approximately 8% of all intracranial tumors which manifest clinically are attributed to schwannomas. The majority of acoustic neuromas are unilateral and sporadic. Bilateral acoustic neuromas are in fact genetic and constitute a bit less than 5% of all schwannomas. Acoustic neuromas in general, tend to present between the fourth to sixth decades of life. Acoustic neuromas developing in individuals with neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF II) are likely to present earlier, with a peak incidence around the third decade of life. Although rare, acoustic schwannomas can occur in children. There is a small female preponderance with an aggravation of problems during pregnancy. The hereditary acoustic neuroma occurs in NF II much more often compared to neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF I), although the latter is much more common. Unilateral acoustic neuroma has been reported exclusively in 24% of cases with NF I, while bilateral acoustic schwannoma is a hallmark of NF II. Both these conditions are autosomal dominant. The defective genetic locus has been localized to chromosome 17 in NF I and chromosome 22 in NF II.[6][7]

Histopathology

The acoustic neuromas arise near the porus acusticus where the transition point between glial and Schwann cells (Obersteiner-Redlich zone) is seen.

Grossly, the tumor is rubbery-firm with a pale, gray color. It shows different degrees of vascularity and has a well-defined capsule, which could be discoursed by the displaced and stretched nerve fibers. The cut section is usually pale gray and firm with a finely trabeculated appearance. Often, evidence of cystic degeneration, hemorrhage, xanthomatous changes and points of calcification may be present and are encountered in large tumors. These changes give a variegated appearance in consistency and color to the giant tumors. The blood supply of the tumor comes mainly from the internal auditory artery, which forks the surface of the tumor with several tiny branches. For larger tumors, there might be blood supply through small branches of the neighboring cerebellar and pontine arteries.

On light microscopy, the tumor is made up of spindle cells that have elongated nuclei and fibrillary cytoplasm. Those cells are arranged in two specific ways: Antoni A and Antoni B. Antoni A tissue is small, with a prominent, organized, interwoven course of elongated bipolar cells. Occasionally, the arrangement of the nuclei and fibers results in a spiral framework simulating that seen in meningiomas. Antoni B is represented by a random gathering of cells grouped around foci of cystic change, necrosis, old hemorrhage, and blood vessels. There is a variable amount of lymphocytic infiltration of this tissue. The Antoni B tissue type, generally seen in large tumors, is thought to be the outcome of ischemia. The consistency of the tumor is determined by the distant relative quantities of these two types. Although these are benign changes, as malignant transformation almost never happens, nuclear pleomorphism is typical in schwannomas. Mitotic figures are relatively rare. Necrosis, if found, is more due to a poor blood supply rather than fast development. Edema, development of micro or possibly macrocysts, xanthomatous alteration, and areas of calcification are attributed to the degenerative changes in the tumor tissue. Electron microscopy (EM) reveals the characteristic basement membrane of the Schwann cells as well as the presence of wide-spaced collagen.[8]

History and Physical

The signs and symptoms of acoustic neuroma are attributed to the involvement of the cranial nerve VIII, compressing surrounding cranial nerves, cerebellum, brainstem, as well as raised intracranial pressure (ICP). The majority of acoustic neuromas present with unilateral hearing loss due to cochlear nerve interruption or impairment of blood supply to the nerve. Other clinical features include tinnitus, decreased word understanding, vertigo, headaches, and facial numbness. With enough growth, the mass at the CPA will eventually compress the brainstem and cause gait abnormalities. The following is a summary of the detailed clinical features.

Due to the involvement of Cranial Nerve VIII

- Auditory

- Hearing impairment: the most common and the earliest symptom, slowly progressive, high frequency retro-cochlear sensorineural type. May pass unnoticed due to its insidious onset. It may be examined in the physical through speech discrimination, using tuning forks of wide-range frequencies, Weber test as well as Rinne test.

- Tinnitus: also a common symptom, can be intermittent

- Vestibular: Instability while moving the head and nystagmus

Due to compression of other Cranial Nerves

- Facial nerve: usually minimal with late presentation except for very large tumors. Depending on the degree of engagement of the nerve, the symptoms may include twitching, increased lacrimation and facial weakness

- Trigeminal Nerve: paraesthesia in the trigeminal distribution, tingling of the tongue, impairment of the corneal reflex, and less commonly pain which may mimic typical trigeminal neuralgia

- The glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves: palatal paresis, hoarseness of voice and dysphagia

Due to Cerebellar Compression

- Occurs in large tumors

- Symptoms include gait ataxia and incoordination of the upper limb, and rarely dysarthria

Due to Brainstem Compression/Torsion

- Symptoms include pyramidal weakness, contralateral cranial nerves involvement, and nystagmus

Due to Raised ICP

These include, but are not limited to, headache, nausea, vomiting, increased blood pressure, decreased mental abilities, confusion, disturbance of level of consciousness, and papilledema.

Evaluation

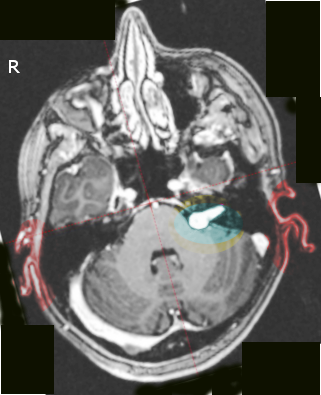

The diagnosis of an acoustic neuroma is made with a contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or a computed tomogram scan. Contrast is essential; otherwise, the non-enhanced scan can miss small tumors. If hearing impairment is present, audiometric tests are needed. Auditory brainstem evoked response is not used frequently to screen for acoustic tumors as it can miss small malignancies.[9][10][11]

The widening of the porus acusticus due to an intracanalicular component causes a trumpeted internal acoustic meatus sign. Tumor growth into the extrameatal space produces the characteristic “ice-cream cone appearance.”

Most acoustic neuromas are hypo to isointense on T1 weighted images and heterogeneously hyperintense on T2-weighted images. There is usually avid contrast enhancement.

Fast spin-echo MRI may be useful as a screening test given its low cost and noninvasiveness.

Treatment / Management

Acoustic neuroma may be treated by:

- Observation if small and in elderly patients with numerous comorbidities

- Stereotactic radiotherapy or

- Open craniotomy. The type of treatment depends on the surgeon experience and patient preferences

The main surgical approaches are:

1. Retrosigmoid: This is the workhorse approach in skull base surgery. It provides good access to the cranial nerves located in this region as well. Tumor of any size can be approached with the possibility of hearing preservation via this route.

2. Middle cranial fossa: This is also a hearing preserving approach that is mostsuitable for tumors with a dominant intracanalicular componentand a small cisternal component. The main disadvantage is the need fortemporal lobe retraction, which may produce postoperative seizures and venous infarct if the vein of Labbe is damaged.

3. Translabyrinthine: Suited for patients with large tumors and no serviceable hearing, The advantage is that facial nerve can be exposed early and protected and the cerebellum need not be retracted. But the access to the contents of jugular foramen and lower parts of the foramen magnum is limited.

After surgery, an MRI is required within 6-12 months to document the extent of tumor removal and serve as a baseline. The most common complications of surgery include injury to the anterior inferior cerebral artery, hemorrhage, cerebellar trauma, facial paralysis, hearing loss (the most common)and hydrocephalus.

Differential Diagnosis

Acoustic neuroma accounts for around 80% to 90% of CPA lesions. Differential diagnosis of an acoustic neuroma include:

- Meningioma (5% to 10% of CPA lesions)

- Ectodermal inclusion tumors

- Epidermoid (5% to 7% of CPA lesions)

- Dermoid

- Metastases

- Neuroma from cranial nerves other than cranial nerve VIII:

- Trigeminal neuroma.

- Facial nerve neuroma

- Neurinoma of the lowest four cranial nerves (IX, X, XI, XII)

- Arachnoid Cyst

- Neurenteric Cyst

- Cholesterol granuloma (distinct from epidermoid)

- Aneurysm

- Dolichobasilar ectasia

- Extensions of nearby lesions in the CPA:

- Brainstem or cerebellar glioma

- Pituitary adenoma

- Craniopharyngioma

- Chordoma and tumors of skull base

- Fourth ventricle tumors (ependymoma, medulloblastoma)

- Choroids plexus papilloma from the fourth ventricle through foramen of Luschka

- Glomus jugulare tumor

- Tumors of the temporal bone

Complications

Most complications are related to the surgery and include the following:

- Injury to the anterior or posterior inferior cerebellar arteries

- Neurological injury

- Brain herniation

- Brain hemorrhage

- Injury to the cerebellum

- Facial paralysis

- Hearing loss

Pearls and Other Issues

Recurrence is not common after removal, but tinnitus may worsen in some patients. Hearing loss and facial paralysis may improve with time.

The pre-operative distinction between a meningioma and an acoustic schwannoma is important for technical and prognostic reasons.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Acoustic neuromas are not common tumors in clinical practice. However, they often present with unilateral hearing loss and thus healthcare workers should consider the lesion in the differential diagnosis. The tumor once diagnosed is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes a neurosurgeon, neurologist, ENT surgeon, and a hearing specialist. After surgery, tinnitus is a common problem in at least 10-20% of patients. The recurrence rate after excision is less than 5%. Facial nerve paralysis appears to occur in about 15-30% of patients but most make a complete recovery over time. Hearing loss occurs in more than 50% of patients and may not improve over time. Residual hearing loss has a significant impact on the quality of life. [12][13][14] (Level V)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

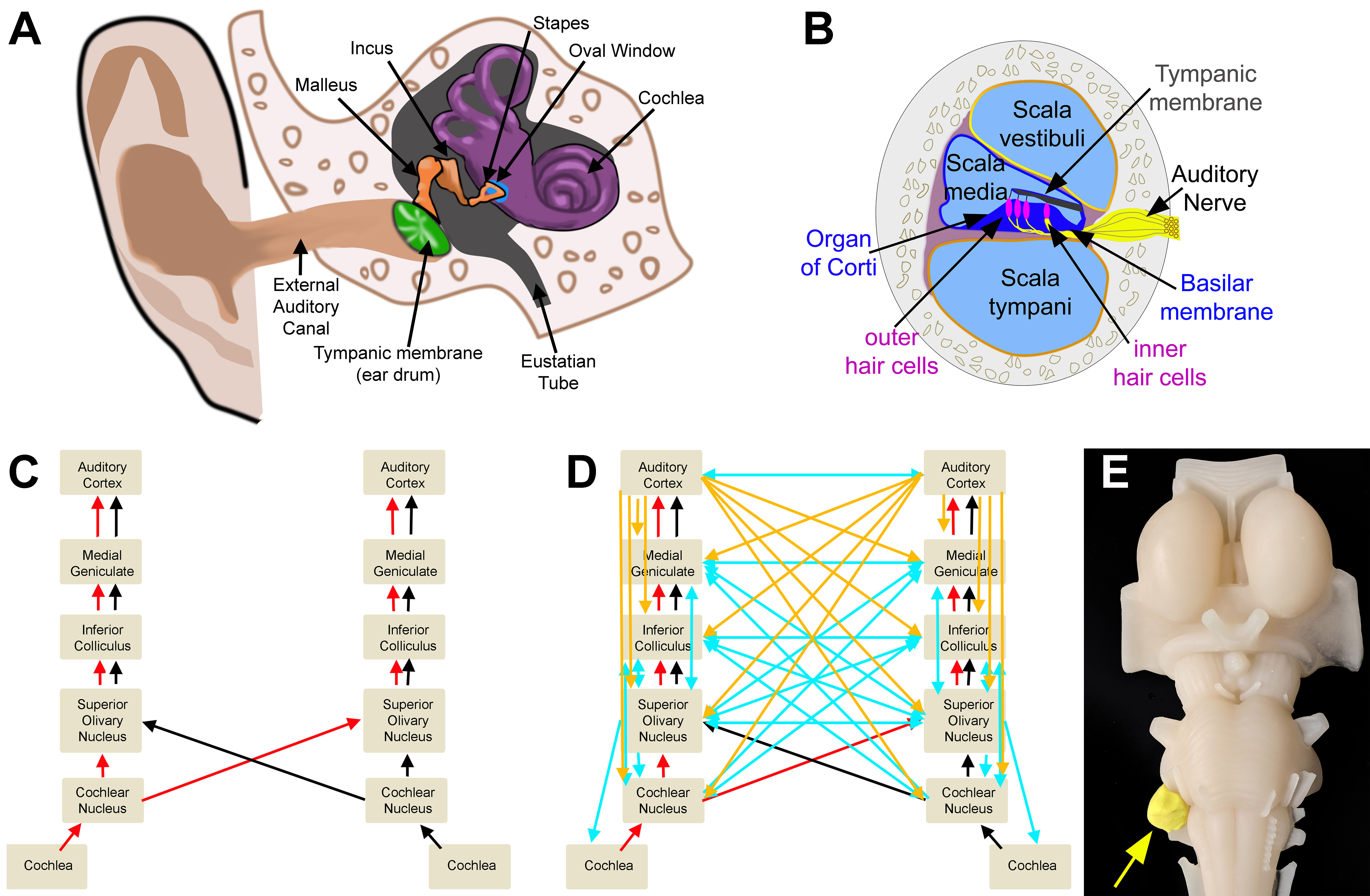

Auditory Circuits. A. Outer, middle, and inner ear. B. Cross section of the cochlea. C. Ascending auditory pathway. D. Ascending (red/black), descending (cortical: orange; brain-stem: blue), and crossed (blue) auditory circuits. E. Model representation of an acoustic neuroma.

All imaging was created by Diana Peterson for the current manuscript.