Actinic Cheilitis

- Article Author:

- Mikel Muse

- Article Editor:

- Jonathan Crane

- Updated:

- 8/8/2020 8:17:10 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Actinic Cheilitis CME

- PubMed Link:

- Actinic Cheilitis

Introduction

“Sailor’s Lip,” or actinic cheilitis (AC), is a precursor of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) found on the lips. Similar to actinic keratosis, actinic cheilitis is a premalignant lesion caused by chronic sun exposure. It is most common on the lower lip along the vermillion border. Given SCC on the lips is considered a high-risk form of skin cancer with an 11% chance of metastasis compared to 1% for other body locations, it is essential to recognize and appropriately manage these potentially malignant precursory lesions.[1]

Etiology

Actinic cheilitis results from the sun or UV radiation exposure. Additional risk factors include increased age, especially over 60 years, Fitzpatrick I and II skin types, genetic abnormalities affecting pigmentation such as albinism, working more than 25yrs outdoors, or a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC). There has been conflicting evidence as to whether alcohol and smoking independently increase the risk of AC.[2]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of actinic cheilitis is higher among fair-skinned populations and those closer to the equator where there is more UV exposure. Men are affected more than women, likely due to their comparatively increased work in the sun and less use of protective lip balm and cosmetics. The exact prevalence of AC is unknown, as the majority of data focuses on the incidence of SCC. In the US, there are more than 3500 new cases of lip cancer annually, 90% are SCC.[3][4] A recent study showed the prevalence of AC in the population over age 45 years old to be 31.3% in northwestern Spain.[5]

Pathophysiology

Those with fair skin have less melanin and innately less protection against UV rays. The physical properties of the lips, such as their shape and being a transition area from oral mucosa to skin with thinner epithelium, less sebaceous glands, and less melanin, contribute to less protection and increased exposure to UV radiation. Chronic exposure to UV light damages tumor suppressor gene p53 resulting in uncontrolled replication of defective cells, which is a common gene mutation found with increasing frequency as actinic cheilitis and actinic keratoses undergo malignant transformation to SCC. Although actinic cheilitis can affect both the upper and lower oral cutaneous mucosa, more light from the sun hits the lower lip, making this area especially prone to sun damage and an increased number of skin cancers.[6]

Histopathology

Biopsy w/ H&E is recommended for persistent suspicious lip lesions to rule out invasive skin cancer. Basic histopathology for actinic cheilitis would be:

- Hyperkeratosis: thickening of stratum corneum

- Solar elastosis: loss of eosin staining, accumulation of irregular thick elastic fibers and tangled fibrillin

- Epithelial dysplasia (mild-moderate): disordered maturation of epidermal cells, loss of rete ridges, variable cytological atypia

- Perivascular inflammation: inflammatory cells around the blood vessels

- Severe dysplasia: increase in dyskeratosis, keratin pearls, drop-shaped projections, and nuclei related changes such as mitoses and pleomorphism indicate the progression of dysplasia and increased malignant transformation.

History and Physical

- Persistent white plaque with “sandpapery” feel on the lips

- Most commonly lower lip

- Blurring of the vermillion border between the cutaneous and mucosal lip

- Usually asymptomatic/painless, but may have burning, numbness, pain

- Eventually, plaque may become indurated, scaly and ulcerate as lesion progresses

- Outdoor laborers: sailors, farmers, construction workers, lifeguards

- Fitzpatrick I-II fair-skinned individuals

Evaluation

Actinic cheilitis is a diagnosis made from clinical and histopathology evaluation. It is essential to distinguish between cheilitis (benign inflammation), premalignant actinic cheilitis, and squamous cell carcinoma. Skin biopsy is the golden standard regarding the evaluation of a persistent suspicious lesion on the lip. Many lesions initially thought to be premalignant actinic cheilitis on exam were found to be SCC upon histological evaluation, which indicates providers are not able to entirely make the diagnosis clinically, and biopsy is helpful when evaluating these lesions. While not required to make a diagnosis, one article suggests evaluating patients with electron microscopy helps to assess further the ultrastructural changes found in AC lesions, their potential for malignant transformation, and ensure they are diagnosed and managed correctly.[7]

- Physical exam: persistent white/erythematous thickening sandpapery skin on the lower lip

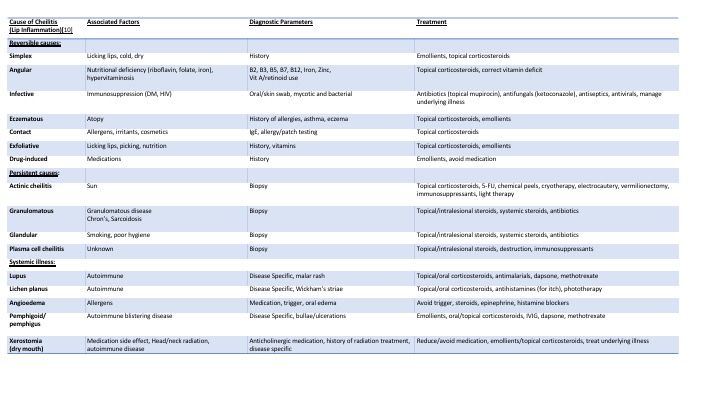

- Labwork: for lesions that are new, symmetric, in young patients, found in patient's with darker skin types, or individuals without a history of chronic sun exposure where skin cancer is less likely, consider first ruling out reversible causes such as those with a vitamin deficiency/infectious/contact/irritant etiology (Chart 1)

- Skin biopsy: skin biopsy is recommended for persistent lesions

- Electron Microscopy: hyperkeratosis, mild acanthosis, Perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate around glandular ducts

Treatment / Management

Treatment of actinic cheilitis should depend on the size, location, and severity of the lesion, along with the patient’s other comorbidities. The goal of therapy is to reduce the risk of malignant transformation from AC to SCC while maintaining functionality and cosmesis of the lips. A variety of therapies targeted at removing the dysplastic epithelium have been used to manage AC, including both surgical and medical options.

Surgical/destructive options for treatment include excisional vermilionectomy, cryotherapy, electrocautery, and pulse-dye or CO2 laser. However, these procedures are invasive, and patients may experience adverse effects such as pain, delayed healing, infection, scarring, edema, and paresthesias.

Non-surgical treatments for AC include topical therapies such as 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, trichloroacetic acid, ingenol mebutate, diclofenac, phototherapy, topical DNA enzyme repair creams, photoprotection, and curettage with methyl aminolevulinate cream/daylight PDT.[3] Many of the topical treatments cause adverse effects such as inflammation, crusting, and pain, which may reduce patient compliance.

A systemic review and meta-analysis of 283 patients showed surgically treated lesions compared to medically managed lesions had a higher remission rate (92.8% vs. 65%) and lower recurrence rates (8.4 vs. 19.2%) than non-surgical treatment.[8] Dermoscopy has been used to aid with diagnosis and monitor treatment management in patients undergoing topical treatment.[9]

It is difficult to directly compare efficacy across the numerous treatment options available for actinic cheilitis since many of the published studies, the severity of actinic cheilitis, and treatment regimens are not consistent or controlled across studies. However, the following options may be an option when deciding management for actinic cheilitis.

Summary of Treatment Options:

- Laser treatment: preferred non-surgical intervention (efficacy 93%, low recurrences)[10]

- CO2 Laser: 10600 nm

- Erbium Laser: 2940 nm

- Adverse effects: pain, hypertrophic scarring (managed with corticosteroids)

- Vermilionectomy/Surgical excision: preferred treatment for severe/refractory cases (efficacy near 100%, low recurrences).[10]

- Adverse effects: pain, delayed healing, infection, scarring, edema, paresthesias, may be cosmetically disfiguring compared to other treatment options

- Topical Treatments: preferred treatment for patients with large areas of sun damage or those preferring medical intervention

- Various treatment regimens studied, examples range from applying to affected area once daily for 1 to 4 weeks depending on patient's tolerability (Efficacy for 5-FU at one week 69%, increased to 91% efficacy at four weeks)

- Adverse effects: pain, crusting, inflammation, reduced patient compliance

- Summary of Topical Options and Their Mechanism of Action

- 5-FU: impairs pyrimidine thymidine synthesis and DNA replication

- Imiquimod: nucleoside analog and immunostimulator

- Ingenol mebutate: induces cell death and neutrophil-mediated antibody-dependent immune response to clear tumors

- Trichloroacetic acid: induces cell necrosis

- Diclofenac: anti-inflammatory, induces apoptosis by inhibiting COX 1 and COX2

- Phototherapy: while actinic cheilitis results from by UV light damaging epithelial DNA, light therapy at an increased intensity level that causes reactive oxygen species to destroy damaged skin cells and was found to be an effective treatment in some cases (efficacy 68%,12% recurrences). Efficacy increases when used in conjunction with other treatment options, including topical treatments.[10]

- Adverse effects include pain, recurrence

- Cryotherapy: liquid nitrogen physically destroys abnormal cells

- Adverse effects include pain, crusting, scarring, reduced efficacy compared to other treatment options

- Electrocautery/Curettage: physical destruction of the abnormal cells

- Adverse effects include pain, scarring

- Photoprotection: reduce the progression

- Dependent on patient compliance

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnoses to consider when evaluating a lesion on the lip include squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, malignant melanoma, herpes, leukoplakia, and a variety of forms of cheilitis. Cheilitis, or inflammation affecting the lips, has a broad differential that can group into reversible, non-reversible, and systemic causes.[11] (Chart 1) Given the malignant potential of lesions on the lip, it may be helpful to obtain a skin biopsy if lesion persists and is refractory to treatment.

Prognosis

Actinic cheilitis is a premalignant lesion, with the possibility of progression into SCC in 6 to 10% of cases. Patients with actinic cheilitis should follow up after treatment with visits at least every six months for the first two years, and annual skin checks after that.[8]

Complications

Reports are as high as 95% of SCC on the lip initially starting as actinic cheilitis. SCC on the lip is much more dangerous than SCC other parts of the body, with 11% of SCC lip lesions metastasizing compared to 1% of SCC found in other anatomical locations.[1]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients can reduce their risks for actinic cheilitis and further malignant transformation of actinic cheilitis into SCC by:

- Sunscreen and UV protective clothing

- Wide-brimmed hats

- Lip balms or makeup containing sunscreen/zinc

- Routine skin checks and follow-up

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The anatomical location of actinic cheilitis on the lip is a location managed by a variety of healthcare providers. Providers in dermatology, dentistry, ENT, and primary care must be aware of actinic cheilitis as a premalignant lesion. They should have a low threshold to biopsy persistent lesions on the lips, especially if the patient has fair skin, a history of sun exposure, or a history of skin cancer. Appropriate monitoring, treatment, and consistent follow up reduces the risk of malignant transformation of actinic cheilitis to SCC. All providers need to be aware and refer a patient if they are not certain of the nature of a lip lesion.