Airway Monitoring

- Article Author:

- Catalina Carvajal

- Article Editor:

- Javier Lopez

- Updated:

- 8/15/2020 11:36:34 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Airway Monitoring CME

- PubMed Link:

- Airway Monitoring

Introduction

Airway monitoring involves assessing both a patient’s ventilatory function and ability to perform the adequate gas exchange. Determining a patient’s airway status is part of a thorough physical exam and interpretation of appropriate adjunct monitors. Like many tools in medicine, monitors provide valuable information to guide the diagnosis and management of patient care. However, they have their limitations and are subject to interpretation. Various airway monitoring modalities will be described and their function and limitations.

Anatomy and Physiology

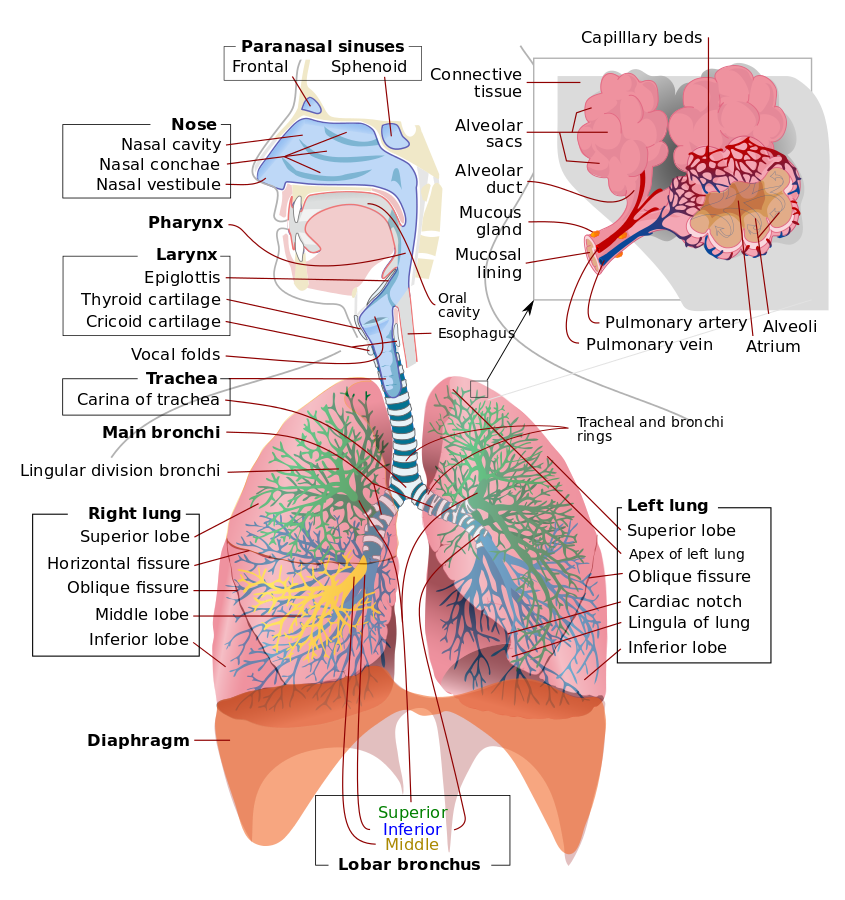

Monitoring a patient in respiratory distress includes both subjective and objective information. A focused history and physical will provide valuable insight into the patient’s ability to protect their airway. Knowledge of the airway anatomy will facilitate a proper airway exam. The airway can be divided into 2: the upper airway and the lower airway. The upper airway extends from the nasal cavity and includes the oropharynx and larynx. The lower airway begins at the level of the trachea and extends throughout the bronchus, bronchioles, and alveoli.

An airway exam should be performed and includes assessing mouth opening, dentition, thyromental distance, neck circumference, Mallampati score, and cervical spine mobility. The mnemonic, LEMON, is often used to evaluate an airway

- L: Look

- E: Evaluate

- M: Mallampati

- O: Obstruction

- N: Neck mobility

Indicators such as a diminished mouth opening less than 3 fingers, large neck, a short thyromental distance less than 3 fingerbreadths, Mallampati 3 or 4, or limited neck extension should alert the provider of a possible difficult airway and prompt for proper preparation.

The most accurate predictor of difficult intubation is an inter-incisor distance of less than 3 cm. Upon intubation, physical exam signs including fogging/mist in endotracheal tube (ETT) lumen, chest rise with each breath, and bilateral breath sounds indicate endotracheal intubation. A chest x-ray may be used to visualize placement. However, it is not required, and clinical correlation is suggested. The most reliable measure of endotracheal intubation is with direct visualization during laryngoscopy and the presence of persistently elevated end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2).[1]

Indications

Airway monitors are useful adjuncts to the physical exam and clinical scenario of each patient. Signs and symptoms such as difficulty speaking, leaning forward in a tripod position, drooling, accessory muscle use, increased work of breathing, nasal flaring, tachypnea, declining mental status, cyanosis, or increasing FiO2 demand are all indicators that a patient will require a secured airway via endotracheal intubation.

Limitations to history and physical may occur with obtunded or altered patients, or in the pediatric population. Should a patient be unable to provide a history, other modalities must be used to assess their airway. Vital signs and labs are good adjuncts that may lead a practitioner to believe a patient is impending respiratory failure. An arterial blood gas, while invasive, provides reliable information and can be used to target management. Physical exam findings confirming endotracheal intubation using breath sounds assumes adequate aeration of lung fields but may be misleading in patients with underlying lung pathology. Waveform capnography continues to be the gold standard confirming proper placement of ETT.

Equipment

Capnography is a method of airway monitoring applicable in both controlled and spontaneously ventilating patients. The amount of infrared light absorbed by carbon dioxide in exhaled gas is measured and reported as a value of concentration. Waveform capnography can provide both qualitative data via waveform analysis and quantitative data via alveolar end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2).[2] Other forms of capnography, such as colorimetric capnography, can confirm endotracheal intubation in remote, out-of-hospital settings, emergency departments or intensive care units. Capnography can provide reliable information confirming adequate ventilation and subsequently cellular gas exchange.

The waveform shows 4 phases of the respiratory cycle:

- Phase 1: The inspiratory baseline

- Phase 2: The expiratory upstroke

- Phase 3: The expiratory plateau

- Phase 4: The inspiratory downstroke

Changes in waveform morphology and amplitude can predict catastrophic events. Increases in ETCO2 may signify rebreathing or hypoventilation, malignant hyperthermia, sepsis, insufflation from laparoscopic surgery, or because of bicarbonate administration. Decreases in ETCO2 are noted during hyperventilation, hypothermia, low cardiac output states (e.g., pulmonary embolism or cardiac arrest), disconnection of the circuit, or accidental extubation. Morphology perturbations such as up-slanting of the expiratory upstroke or prolongation of the plateau phase can be evidence of airway obstruction seen in bronchospasm, asthma, pregnancy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or a kinked endotracheal tube (ETT). Waveform capnography is an essential monitor in all intubated patients, and its interpretation can guide ventilatory management.

Capnography has its limitations, especially when a patient is not intubated or no other secure airway is in place. Positive return of end-tidal carbon dioxide alone may or may not confirm endotracheal placement of ETT. A sustained greater than 30 mm Hg ETCO2 for 3 breaths minimum will confirm tracheal placement. Additionally, if a patient drank a bicarbonate solution or carbonated beverage before intubation, this may also alter ETCO2. Capnography requires cardiac output, and therefore its use is limited in pulseless patients. It may be used to target chest compressions where a sudden rise may indicate a return of spontaneous circulation.

The pulse oximeter is a non-invasive monitor used to detect changes in hemoglobin oxygenation saturation and heart rate. Pulse oximetry functions on spectrophotometry and photoplethysmography. Oxyhemoglobin absorbs infrared (IR) light at a wavelength of 940 nm, and deoxyhemoglobin absorbs red (R) light at a wavelength of 660 nm. When oxyhemoglobin absorbs emitted infrared light, it allows red light to be transmitted and received by the photodetector. The ratio of red light to infrared light is used to determine the percent of hemoglobin oxygen saturation. The pulsations occurring with each heartbeat are recorded as arterial blood and thus provide arterial blood oxygenation.[3]

While there are many benefits to having a pulse oximeter to depict the quantity of blood oxygenation, this monitor has several limitations. One case is carbon monoxide poisoning resulting in carboxyhemoglobin, which, together with oxyhemoglobin have the same absorption wavelength of 660 nm and therefore, can demonstrate a falsely elevated oxygen saturation. Similarly, with methemoglobinemia, which has the same absorption coefficient at both red and infrared light (resulting in a 1:1 R/IR ratio), depicts a saturation of approximately 85%. This phenomenon results in a falsely low oxygen saturation when the saturation is greater than 85%, and falsely elevated saturation when the saturation is less than 85%. Additional considerations include accuracy of oxygen saturation in situations of acid-base disorders, severe hypoxemia less than 70% SaO2, dark blue, purple, or green nail polish. Likewise, conditions involving excessive motion, ambient light, low perfusion due to low cardiac output, hypothermia, increased systemic vascular resistance, profound anemia, methylene blue dye, and malpositioning may also alter readings and should be considered.

Personnel

All personnel involved in patient care should recognize the signs of respiratory distress. A clinician trained in advanced airway management should be consulted immediately, and measures to obtain objective information should be performed. When a difficult airway is anticipated, video-assisted laryngoscopy should be available as a backup tool should the need to secure the airway arise. A careful review of the difficult airway algorithm should be performed in all potentially difficult to ventilate/intubate patients.

Clinical Significance

Monitoring the airway of an intubated patient is dependent on numerous variables. The ventilator can provide a visual representation of a patient’s ventilatory mechanics and is sensitive to acute changes. Radiographic imaging may provide information on developing lung pathology or diaphragmatic abnormalities. Weaning from a ventilator also requires proper airway monitoring to ensure the patient is capable of maintaining and protecting their airway. Specific criteria must be followed to perform extubation safely and prevent the need for re-intubation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patient-centered care is best achieved through an interprofessional approach through interprofessional communication. The nursing staff and emergency medical services are among the first members of the healthcare team to monitor and assess a patient's airway. Guidelines established by the American College of Surgeons Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) course and the American Heart Association have made airway management the top priority when assessing a patient. Pre-hospital basic airway management for patients at risk for airway compromise ensures the best outcomes in morbidity and mortality for when the patient reaches in-hospital care.[4] (Level I)

Physicians, nurse anesthetist, respiratory therapists, nurses, radiologists, and pharmacists all play an important role in not only detecting early airway compromise but also in the event of an emergency endotracheal intubation. Proper advanced airway management is vital, and an expert skill level is required. Incorrect placement of an advanced airway can cause gastric insufflation, hypoxia resulting in anoxic brain injury, alterations in blood gases and acidosis, ischemia to vital organs, and if not corrected may cause death.

Adequate ventilation is critical to life, which is why an interprofessional approach is the best way to improve outcomes in patients. All members of the interprofessional healthcare team should monitor the patient and alert the physician, nurse anesthetist, or respiratory therapist of a patient in impending respiratory failure. A radiologist can provide information on specific lung pathology or confirm the proper positioning of an endotracheal tube. Likewise, a respiratory therapist may detect early signs of worsening lung mechanics and patient symptomatology. Pharmacists play an important role in having available the medications that will facilitate a rapid sequence induction and intubation. Further, they must guide the clinicians in the selection of appropriate drugs to assist intubation and avoid drug interactions or complications. If intubation is unsuccessful or suspected to be a difficult airway, it is advised to consult an anesthesiologist or nurse anesthetist if the patient is in a hospital setting. (Level V)