Ameloblastoma

- Article Author:

- Jaishree Palanisamy

- Article Editor:

- Andrew Jenzer

- Updated:

- 8/24/2020 11:01:08 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Ameloblastoma CME

- PubMed Link:

- Ameloblastoma

Introduction

The word ameloblastoma derives from the early English word “amel,” meaning enamel and the Greek word “blastos,” meaning germ. They are rare, odontogenic tumors, thought to be composed of the epithelium of ectodermal origin, which means they are tumors arising from the cells around the tooth root, or in close approximation, derived from the ectoderm germ layer. Ameloblastomas represent about 1% of all jaw tumors, but they are the second-most common odontogenic tumor. They are much more common in the lower jaw than in the upper jaw, and more common in the posterior mandible as compared to the anterior. The vast majority of the time, they are a benign tumor with aggressive behavior; however, rarely they can develop into, or be associated with, a malignancy (malignant ameloblastoma or ameloblastic carcinoma). It is extremely rare to find ameloblastomas outside the maxilla and mandible due to the association with teeth and their structures.

Anatomy: There are 20 deciduous teeth (“baby teeth”) and 32 permanent teeth (generally depending on third molar development or wisdom teeth) that start to appear in the mouth around 6 years of age. The last four permanent teeth to erupt are third molars or "wisdom teeth," each of which may or may not grow in. Among deciduous teeth, ten usually are found in the maxilla (upper jaw), and ten are in the mandible (lower jaw). For permanent teeth, 16 are in the maxilla, and 16 are in the mandible.

There are specific anatomic landmarks unique to each type of tooth which define them as incisors, molars, canines, etc. The anatomy of the tooth itself consists of the root which is hidden in the gums, and the crown, or visible part. The root of the tooth is anchored to the bone to which it is associated and allows for blood flow and nerve supply to the tooth to maintain viability. This system of ligamentous attachment connecting the tooth to the surrounding socket is called the periodontium. The hard tissue covering the crown is the enamel. The root is covered by cementum, a substance that is a hardy mineral but softer than enamel.

Natural History: The vast majority of ameloblastomas are benign and slow-growing, with locally aggressive behavior, which can lead to significant pathology and require extensive surgical treatment. The abnormal cell growth easily infiltrates local tissue, typically bone. Surgical excision is usually needed to treat this disorder. It has a high propensity for local recurrence even with proper surgical management and requires lifelong follow up for surveillance.

Patterns of spread: Amelomlastomas spread locally, invading surrounding tissues. They spread through bone and can invade soft tissues as well if given enough time to do so. However, this is a benign tumor so metastasis to lymph nodes, distant sites, etc., is rare and changes the staging to malignant. The thinking is that malignant ameloblastomas comprise less than 1% of all ameloblastomas.

Etiology

Ameloblasts are of ectodermal origin and derived from oral epithelium. The cells are only present during tooth development that deposit tooth enamel, which forms the outer surface of the crown. Ameloblasts become functional only after odontoblasts form the primary layer of dentin (the layer beneath enamel). The cells eventually become part of the enamel epithelium and eventually undergo apoptosis (cell death) before or after tooth eruption.

There exist deposits of these cells in the structures in and around the tooth, termed cell rests of Malessez and cell rests of Serres. Current thought is that ameloblastomas can arise from either the cells mentioned above or other cells of ectodermal origin, such as those associated with the enamel organ.

Approximately 80% occur in the mandible and the other 20% in the maxilla.

Epidemiology

Ameloblastomas can occur over a broad age range, and most commonly affect patients between the ages of 20 to 40 years. They are uncommon in children younger than ten years. Males and females are equally affected. Ameloblastomas are located most commonly in the posterior mandible, with fewer tumors arising in the maxilla.

Rizzitelli A et al. conducted a population-based study of malignant ameloblastoma to determine it’s incidence rate and absolute survival. They looked at 293 patients across the United States and found that the overall incidence rate of malignant ameloblastoma was 1.79 per 10 million persons/year. The rate of incidence was higher in males than females and also higher in the black versus white population. They also found that malignant ameloblastoma, comprising the two types, metastasizing ameloblastoma, and ameloblastic carcinoma, represents 1.6 to 2.2% of all odontogenic tumors. Their findings confirmed previous epidemiologic research, which showed the male to female ratio to be between 2.3 and 5[1].

There do exist variations that tend to arise in specific populations. The ameloblastic fibroma is similar to ameloblastoma, but with a different histopathologic presentation. They generally occur in the age group between 10 to 16 years of age. Treatment involves simple enucleation and curettage as opposed to 10 mm margins with ameloblastoma. The ameloblastic fibro-odontoma is another variation and typically arise in patients aged 6 to 10. Treatment is enucleation and curettage. Radiographs and demographics are vital in making these diagnoses.

Malignant variations of the ameloblastoma can occur between the teenage years up to older age.

Pathophysiology

The cause of ameloblastoma is not well understood. There is recent evidence that genetic mutations that activate a specific signaling pathway (MAPK) play a role in the pathogenesis of ameloblastoma. Further understanding of the molecular basis of tumorigenesis will have implications for diagnosis and therapy.

Histopathology

Histologically, it is most important to differentiate common ameloblastomas vs. ameloblastic carcinoma/malignant ameloblastoma.

Ameloblastic carcinoma is generally more aggressive and has a worse prognosis in late disease. Ameloblastic carcinoma has certain features of benign ameloblastoma such as reverse polarization, peripheral palisading, and stellate reticulum-like cells. It has features of malignancy common to many cancers such as high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, increased mitoses with atypical forms, cytological atypia, and necrosis. The following are some features of ameloblastic carcinoma[1][2]:

1) High mitotic figure

2) Cellular atypia

3) High proliferative mitotic index

4) Perineural or perivascular invasion

5) Nuclear atypia such as nuclear pleomorphism

Malignant ameloblastoma, on the other hand, has these histological features:

1) Lack of mitotic figure

2) Normal ameloblastic cells

3) Lack of a mitotic index

4) No perineural or perivascular invasion

5) Normal polarized ameloblastic nucleus

History and Physical

Ameloblastomas usually are asymptomatic until the patient notices intraoral or facial swelling. Patients often present with progressive maxillary or mandibular expansion and facial asymmetry. Pain and altered sensation are uncommon. Patients may complain of a change in bite and loose teeth. Smaller tumors are usually detected first on routine dental radiographic exams. Untreated tumors can grow to massive proportions and cause facial deformity, as exhibited, especially in third world countries where patients can go for long periods before seeking treatment or having access to care.

Evaluation

Tumor and characteristics are assessed using the patient’s history, clinical exam, and imaging, most commonly computed tomography (CT). On CT scan, ameloblastomas appear as radiolucent (radiographically dark) lesions of the maxilla or mandible, often with multilocular or “soap-bubble” appearance, bony expansion and tooth root resorption. They may also be associated with unerupted teeth. A definitive diagnosis of ameloblastoma is with a surgical biopsy, which shows characteristic histologic findings. It is essential to differentiate the entity from a primary intraosseous squamous cell carcinoma.

The World Health Organization (WHO) classified malignant ameloblastoma into two types[3]:

- Metastasizing ameloblastoma

- Histologically similar to benign ameloblastoma but shows metastatic spread to distant sites

- Ameloblastic carcinoma

- Shows malignant features on histology

- Can be further subdivided into two subtypes:

- Primary ameloblastic carcinoma: arises de novo (from Latin meaning "anew")

- Secondary ameloblastic carcinoma: the eventual result of malignant transformation of a previously diagnosed benign ameloblastoma

Treatment / Management

Mural and solid ameloblastomas are treated with complete surgical excision with normal bone margins at a minimum of five to fifteen mm, though ten mm margins are most common. Reported recurrence rates are up to 70%, with incomplete resection being the most common reason for the high recurrence rate. Enucleation and curettage, cryotherapy and marsupialization have all been used to treat ameloblastomas; however, these modalities are not curative and are not standard of care now.

Ameloblastic carcinoma treatment is generally via surgical resection with 2 to 3 cm margins. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy is an option after resection for positive margins or perineural invasion. In malignant ameloblastoma, surgical resection with 1 to 2 cm margins is usually the treatment modality of choice, and no chemotherapy or radiotherapy is generally required.[4]

Since malignant ameloblastoma is typically a slow-growing tumor, more active treatment approaches such as chemo or radiotherapy may not be necessary. Close patient follow-up for a minimum of five years is necessary to monitor for recurrence.

Practitioners follow the most current recommendations from the American Joint Committee on Cancer and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network for more detailed treatment modalities, indications for neck dissections, chemo, and radiotherapy, etc.

Differential Diagnosis

It is difficult to differentiate benign ameloblastoma from malignant ameloblastoma on histology alone as it can look benign on histology but be clinically invasive or even metastasize. Benign ameloblastoma is histologically identical to malignant ameloblastoma but has no metastases. However, malignant variations are extremely rare, with only approximately 30 cases of malignant ameloblastoma in the literature, and about several hundred cases of ameloblastic carcinoma.

Ameloblastic fibroma may share the same features histologically, such as small cords and islands of ameloblastic epithelium that's just two cells thick containing dense collagenous stroma which is often immature. It can also occasionally contain cementum or dentin production as well as stellate reticulum. The main feature of ameloblastic fibroma is that the stroma is more primitive and it should not metastasize.

Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the lung and metastatic disease in the lung that has spread will have histologic features of malignancy but no other features of ameloblastoma (no polarization, no peripheral palisading, no stellate cells, etc.).

Surgical Oncology

Practitioners follow the most current recommendations from the American Joint Committee on Cancer and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network for more detailed treatment modalities, indications for neck dissections, chemo, and radiotherapy, etc. These guidelines are updated annually.

Radiation Oncology

Practitioners follow the most current recommendations from the American Joint Committee on Cancer and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network for more detailed treatment modalities, indications for neck dissections, chemo, and radiotherapy, etc. These guidelines are updated annually.

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

There is a Phase 2 study at Stanford University titled A Pilot Study of Dabrafenib and Trametinib for Patients With BRAF Mutated Ameloblastoma which studies dabrafenib and trametinib in treating patients with ameloblastoma and a specific mutation in the BRAF gene. The study authors believe Dabrafenib and trametinib may halt the growth of tumor cells by blocking enzymes needed for cell growth. The study is currently the only one looking at a specific treatment for ameloblastomas. It started in July 2017 and is currently recruiting. The study has an estimated completion date of August 2020, and they are expected to enroll 17 participants.

During the study, patients receive dabrafenib orally (PO) two times daily every 12 hours and oral trametinib 2 mg daily for 6 weeks in the absence of disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Patients with disease determined to be not amenable to resection will indefinitely continue dabrafenib and trametinib as long as there has been no tumor progression.

Following the completion of the study therapy, patients are followed up for at least 4 weeks.

It is worth noting that this study addressed ameloblastomas, not a malignant variation.

Treatment Planning

Treatment completion will be by a surgeon trained in head and neck surgery, typically an oral and maxillofacial surgeon, otolaryngologist, plastic surgeon, or oncologic surgeon. Often, case planning can include either immediate or delayed reconstruction. Treatment planning is critical, especially when involving teeth, as extractions of teeth in the lesion are often completed and permitted to heal before access through the neck, thus preventing communication with the oral cavity and associated bacteria.

Staging

Currently, there is no staging system for ameloblastoma due to the absence of prospective studies for this very rare disease.

Prognosis

Unfortunately, malignant ameloblastoma is too rare to estimate its prognosis. Due to its slow-growing nature, the malignancy may not occur for up to 10 years after initial resection of benign ameloblastoma.

Complications

The complications of malignant ameloblastoma are usually due to its local invasiveness or distant metastatic spread. In terms of local complications, it can lead to progressive maxillary and mandibular distortion leading to deformity, pain, and malocclusion.

Consultations

Consider consultation with a dentist, OMS, and/or ENT surgeon.

Deterrence and Patient Education

It is essential to educate patients on the usually benign nature of ameloblastomas, but a high rate of recurrence. Keeping patients informed of the importance of regular follow up is crucial to monitor any benign or possible malignant ameloblastoma since it is difficult to differentiate between the two histologically.

Pearls and Other Issues

A small percentage of ameloblastomas (two percent) are peripheral and located in the soft tissues of the oral cavity. Rarely, ameloblastomas can undergo a malignant transformation or can metastasize to distant sites such as the lymph nodes and lungs. The vast majority of ameloblastomas are the benign, but aggressive type. These patients will need surgery and life long follow up.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

It is crucial to have an interprofessional team approach to the management of malignant ameloblastoma. It is vital to have oral-maxillofacial surgeons and plastic surgeons involved in any possible reconstruction needs after surgical excision. Head and neck trained surgeons familiar with the complete surgical excision of malignant ameloblastoma are central to complete tumor excision. Speech-language pathologists and voice therapists are important post-operatively for the management of voice and swallowing issues that may arise after surgical excision.

The dietitian should be involved early in the care as many patients after surgery will have trouble eating. Healing of the oral tissues can take weeks or months, and hence, consideration to enteral or parenteral feeding may be necessary. The nurses should also assess the oxygenation, breathing, and assist with suctioning the oral cavity. Aspiration is also a risk after surgery, and the patients need to have the head of the bed elevated. Also, the patients need DVT and stress ulcer prophylaxis. Since major surgery in the facial area can also result in severe aesthetic changes, a mental health nurse should counsel the patient. Finally, the pain team should have involvement as postoperative pain can be significant. Pharmacist involvement comes in the form of assisting in pain management as well as those cases where chemotherapy is an option. All these professionals need to maintain open lines of communication with other providers so that interprofessional effort leads to optimal patient outcomes. [Level V]

Though radiation and chemotherapy are not the mainstem of treatment for malignant ameloblastoma, it is important to involve them in select cases where chemoradiotherapy may be of benefit. The entire team should communicate on patient care plans to ensure the best outcomes.

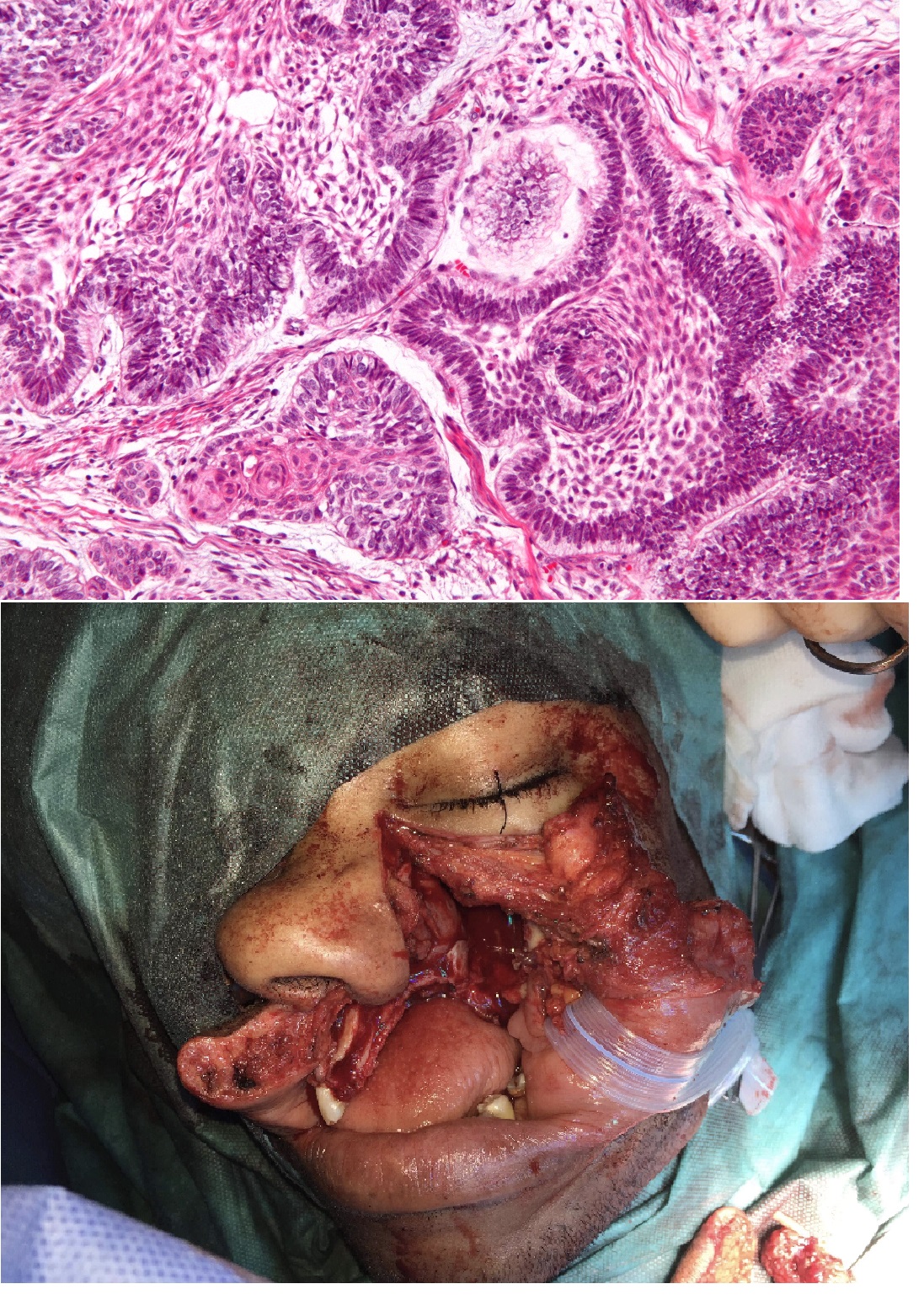

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Top) High magnification micrograph of an ameloblastoma. H&E stain. The images show the characteristic features: Islands of cells with palisaded nuclei that have reverse polarization. Reverse polarization of nuclei = nuclei distant from the basement membrane/nuclei at pole opposite of basement membrane. Palisaded nuclei = picket fence appearance; columnar-shaped nuclei with long axis perpendicular to the basement membrane. Subnuclear vacuolization in palisading cell - vacuoles at the basement membrane aspect. Loose stroma around the islands of cells. Star-like cells at the centre of the islands of cells (stellate reticulum). (Bottom) Lip split with hemimaxillectomy for ameloblastoma growing into the maxillary sinus leading to significant pain and compressive symptoms. The defect was closed with a fibular free flap.

(Top) Nephron [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)] (Bottom) Contributed by Jaishree Palanisamy, DO