Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Forearm Anterior Interosseous Nerve

- Article Author:

- Alex Wertheimer

- Article Editor:

- John Kiel

- Updated:

- 7/31/2020 5:33:42 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Forearm Anterior Interosseous Nerve CME

- PubMed Link:

- Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Forearm Anterior Interosseous Nerve

Introduction

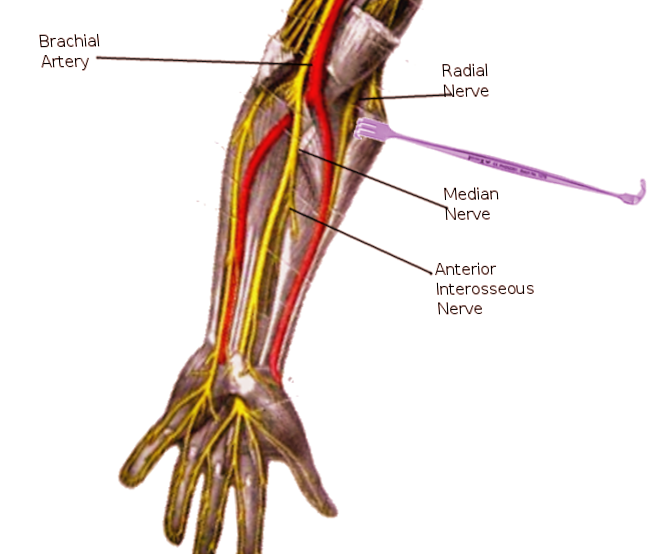

The anterior interosseous nerve (AIN) is predominantly a motor neuron. It is a branch of the median nerve, which is formed from the roots of the fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth cervical nerves as well as the first thoracic nerve. These nerve roots form the brachial plexus which divides to form the medial and lateral cords and then converge to form the median nerve. The anterior interosseous nerve branches off the median nerve at the radiohumeral joint line, approximately 4 to 6 cm distal to the medial epicondyle and 5 to 8 cm distal to the lateral epicondyle. It then passes between the two heads of pronator teres, runs along the volar surface of the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP), courses along the interosseous membrane between the ulna and radius and FDP and flexor pollicis longus (FPL), branches to innervate these muscles, and ends in the pronator quadratus (PQ) near the wrist joint. The anterior interosseous nerve innervates three muscles: flexor digitorum profundus (FDP), flexor pollicis longus (FPL), and pronator quadratus (PQ).[1]

Structure and Function

The AIN provides motor innervation to deep forearm muscles, including flexor digitorum profundus (radial half/index and middle finger), flexor pollicis longus, and pronator quadratus. It also provides some sensation to distal radioulnar and carpal joints and joint capsule. It does not provide cutaneous innervation.[1]

Physiologic Variants

Martin-Gruber anastomosis occurs in 10% to 15% of all forearms (motor nerve connection between the median and ulnar nerves). In 50% of these cases, the nerve communication from the median nerve arises from the AIN branch. Therefore, palsy of the AIN could lead to palsy of the intrinsic muscles of the hand normally supplied by the ulnar nerve.[2]

Surgical Considerations

AIN Compressive Neuropathy

The surgical decompression of the AIN is indicated only if a prolonged period of nonoperative treatment fails. The technique may include the release of the superficial arch of flexor digitorum superficialis and lacertus fibrosus, detachment of superficial head of pronator teres, ligation of any crossing vessels, and removal of any space-occupying lesion.[3]

Pediatric Supracondylar Fracture

Closed reduction and percutaneous pinning (CRPP) is indicated in type II and III supracondylar fractures, flexion type, or medial column collapse. The urgency of this surgery depends on the clinical presentation. Of note, an isolated AIN injury is not an urgent surgical consideration and can be done electively.[4]

Clinical Significance

Clinical Exam

The anterior interosseous nerve exam is performed by testing the motor function of the FDP, FPL, and PQ. The flexor digitorum profundus is tested by requesting the patient to bend the tip of their second and third digit while stabilizing their proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint. In uninjured patients, they will be able to flex their distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint. The flexor pollicis longus can be tested by instructing the patient to bend the IP joint of their thumb. The pronator quadratus is tested by having the patient's arm at their side with the elbow flexed to 90 degrees and the forearm in supination. The examiner then asks the patient to pronate their forearm while providing resistance. As with all orthopedic exams, the affected limb should be compared to the unaffected limb.[5]

AIN Syndrome

AIN syndrome typically presents as forearm pain and partial or complete dysfunction of the AIN innervated muscles (FPL, FDP to the index finger [FDP1] and middle finger [FDP2] and PQ muscle). The AIN may become entrapped in any of the following locations: tendinous edge of deep head of pronator teres (most common cause), flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) arcade, edge of lacertus fibrosus, accessory head of FPL (Gantzer muscle), accessory muscle from FDS to FDP, and aberrant muscles (flexor carpi radialis brevis, palmaris profundus). However, it is most commonly the result of a transient neuritis. As stated above, a patient presenting with complete AIN palsy would typically present with partial or complete loss of motor function to FDP1, FDP2, FPL, and PQ. The FDP2 function may be preserved because of cross innervation by the ulnar nerve. The patient will demonstrate grip and pinch weakness, specifically thumb, index, and middle finger flexion. The patient will be unable to make an “OK” sign (Kiloh-Nevin sign) due to the inability to flex the thumb interphalangeal (IP) joint and the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint of the index finger, which is an indication of complete loss of function of the FPL and FDP1. This weakness can be further evaluated by asking the patient to pinch a sheet of paper between the thumb and index finger using only the fingertips while the examiner slowly pulls the paper away. A patient with AIN will compensate for their FPL and FDP1 weakness by using their hand intrinsic muscles innervated by the ulnar nerve. The patient will also demonstrate weakness with resisted pronation with elbow maximally flexed (this tests the PQ). Patients with Martin-Gruber anastomosis can present with weakness of the hand intrinsics typically supplied by the ulnar nerve. The AIN does not provide sensory innervation to the skin, so there will be no sensory deficits in an isolated AIN palsy.

The differential for a patient presenting with suspected AIN syndrome includes trauma, FPL tendon rupture, proximal sites of nerve compression (i.e., cervical nerves, brachial plexus) thoracic outlet syndrome, pronator syndrome, carpal tunnel syndrome, and Parsonage-Turner syndrome. Parsonage-Turner syndrome is a bilateral AIN neuropathy caused by viral brachial neuritis. This diagnosis is more likely if the motor loss is preceded by intense shoulder pain and viral prodrome. FPL rupture is typically seen in rheumatoid arthritis or with a history of trauma and is distinguished from AIN compressive neuropathy with passive flexion and extension of the wrist. An intact FPL tendon will cause the thumb IP joint and index finger DIP joint to flex during this motion. Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies (NCS) can be used to help rule out other more proximal lesions and assess the severity of AIN compressive neuropathy. Typically, imaging is not helpful for the diagnosis and treatment of AIN syndrome. The majority of patients will improve with nonoperative management, including rest and splinting in 90 degrees flexion for 8 to 12 weeks. Surgical decompression of AIN is indicated if nonoperative management fails.[3][6][7]

Pronator Teres Syndrome

AIN syndrome should be distinguished from pronator teres syndrome (PTS), a distinct but similar proximal median neuropathy. PTS is characterized by vague forearm pain associated with paresthesia of the median nerve. This is distinguished from AIN neuropathy which is a pure motor palsy.[5]

Pediatric Supracondylar Fractures

AIN neuropraxia is the most common nerve palsy seen with pediatric supracondylar fractures. AIN palsy is found in 7.6% to 8.6% of supracondylar fractures and by itself, makes up 47% of all nerve-related complications and 70% of median nerve injuries. The mechanism of injury is typically a fall onto an outstretched hand. Patients most often present with pain and refusal to move the elbow. Physical exam consistent with a supracondylar fracture will reveal gross deformity, swelling, ecchymosis in the antecubital fossa, and limited active elbow motion. If there is AIN neuropraxia, the patient will be unable to flex the interphalangeal joint of the thumb and the distal interphalangeal joint of the index finger (cannot make an "OK" sign). The mechanism of injury for AIN in supracondylar fractures is tenting of the nerve on the fracture or entrapment in the fracture site. X-ray findings indicative of a pediatric supracondylar fracture include posterior fat pad sign (lucency on a lateral view along the posterior distal humerus and olecranon fossa is highly suggestive of occult fracture around the elbow). Other findings include displacement of the anterior humeral line and alteration of the Baumann angle. Nearly all cases of neuropraxia following supracondylar humerus fractures resolve spontaneously. Operative management is indicated based on the severity of the fracture.[4][8]