Shoulder Arthrocentesis Technique

- Article Author:

- Seth Baruffi

- Article Author:

- Ahmed Saber

- Article Author:

- Tiago Martins

- Article Editor:

- Matthew Varacallo

- Updated:

- 9/20/2020 10:49:33 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Shoulder Arthrocentesis Technique CME

- PubMed Link:

- Shoulder Arthrocentesis Technique

Introduction

Shoulder arthrocentesis (shoulder aspiration) is a necessary and practical skill in the hands of emergency physicians, surgeons, medical specialists, and primary care providers. A clinically useful procedure for both diagnostic and therapeutic indications, shoulder joint aspiration as a diagnostic procedure limited relative contraindications. [1]

Shoulder aspiration/injection techniques are commonly utilized in various treatment and management modalities. Aspiration techniques are often used in clinical settings that require synovial fluid analysis to aid in the diagnosis of inflammatory or septic arthritis. In addition, shoulder aspiration techniques can be used in rheumatologic and traumatic causes, such as when attempting to clinically differentiate between suspected cases of infection versus gout, pseudogout, and/or traumatic hemarthroses.[2]

Therapeutically, the technique is utilized to aspirate (or "drain") shoulder joint effusions in addition to coupling the aspiration with the injection of a local steroid and/or anesthetic for pain relief and to facilitate shoulder reduction in an awake patient. The latter can be beneficial for the patient and help mitigate other risks associated with procedural sedation and IV pain medication use. Glenohumeral intra-articular injections can also be utilized in the setting of pain/symptomatic management of shoulder degenerative joint diseases.

In the setting of clinical suspicion for periprosthetic joint infections (PJI), in this case following either a standard total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA), reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (rTSA), or a shoulder hemiarthroplasty, aspirations sent for extended culture incubation time periods (i.e. 2 to 3 weeks) can be clinically useful to aid clinicians in the appropriate management of these conditions. [3][4]

Anatomy and Physiology

To prevent complications, the clinician should be familiar with the glenohumeral (GH) joint and shoulder girdle anatomy.

Osseous elements

The shoulder girdle itself consists of the scapula and clavicle which articulate with the chest wall, and the proximal humerus which articulates with the scapula (the glenoid). The humeral head and the glenoid vault of the scapula form the osseous components of the glenohumeral joint of the shoulder.

Surrounding osseous components that can potentially be implicated in associated/related pathologic conditions include the other portions of the scapula, including the body, spine, and most laterally, the acromion. The latter can be implicated in conditions relating to shoulder external impingement and rotator cuff syndrome [5][6][7].

Soft tissue components

Bursa

Shoulder injections technique can include extra-articular and periarticular injections to various anatomic locations. The most common location is the subacromial space of the shoulder. The subacromial space exists as a bursal cavity lying between the rotator cuff (inferiorly) and the acromion process (superiorly). In addition, the most lateral component of this cavity becomes contiguous with the subdeltoid bursa/space.

Neurovascular elements

Critical knowledge of the surrounding neurovascular structures is of the utmost importance when planning for a shoulder joint aspiration/injection.

The shoulder joint derives its nerve supply from three branches of the brachial plexus (C5/C6):

- Suprascapular nerve

- Axillary nerve

- Lateral pectoral nerve

The axillary nerve and the posterior circumflex humeral artery pass through the quadrilateral or quadrangular space, which lies inferior and posterior to the GH joint. The quadrangular space includes the following borders/boundaries:

- Superior: Teres minor

- Inferior: Teres major

- Medial: Long head of the triceps

- Lateral: Proximal humerus/humeral shaft

Indications

Diagnostic Indications[8][9][10]

- Diagnosis of infectious/septic arthritis

- Diagnosis of inflammatory arthritides/crystalline arthropathy

- Diagnosis of traumatic injury (bony or ligamentous)

- Rule out traumatic arthrotomy (in the setting of penetrating trauma, lacerations, gunshot wounds (GSW))

Therapeutic Indications

- Steroid/cortisone injections

- Local anesthetic injections

- Relief of symptomatic, distended effusions

- Relief of hemarthroses to prevent synovial hypertrophy and fibrosis

Contraindications

The only absolute contraindication to the procedure is cellulitis overlying the entry point; however, known bacteremia is a relative risk as this procedure in the bacteremic patient could theoretically seed the joint space. High suspicion for bacterial joint infection should prompt synovial fluid analysis even in the bacteremic patient as the risks of improper or incomplete treatment of a septic joint far outweigh the theoretical risk of seeding the joint with bacteria. Another relative contraindication is a bleeding disorder or anticoagulant therapy as this could introduce hemarthroses; however, this risk is low compared to risks associated with bacterial joint infection. Prosthetic joints are considered to be a relative contraindication by some outside of a sterile, surgical environment. However, emergent arthrocentesis may be required if a sterile OR environment is not available.

Equipment

Materials

Aseptic Skin Preparation

- Sterile gloves

- Iodine solution or chlorhexidine skin prep

- Sterile gauze pads

- Sterile, fenestrated drape

Needles

- 25G or 27 G for anesthetic and steroid injection

- 20-22 G for aspiration (depending on viscosity fluid to be aspirated)

Luer-Lok Syringes

- 3-5 mL for injection

- 5-20 mL for aspiration

Medications

- Anesthetic: Lidocaine 1% or Bupivacaine 0.5% (shoulder will accommodate 3-5 mL)

- Steroid: Methylprednisolone acetate (Depo Medrol) 40 mg or Triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog) 40 mg

Testing Equipment

Specimen collection tubes

- Hematology tube for cell count and differential

- Sterile tube for Gram stain, culture, and smear

- Heparinized tube for crystal analysis

Preparation

As with any medical procedure, the keys to success often lie in thorough preparation. Since there are no hyperacute indications for arthrocentesis of the shoulder, adequate preparation time should always be taken to maximize success and to minimize risk.

Technique

Anesthesia

- The skin overlying the area of injection can be anesthetized with localized infiltration of 1% lidocaine and a high gauge needle. Alternatively, rapidly evaporating coolants such as ethyl chloride work to provide short-acting anesthesia of the skin at the point of injection. These techniques can be used in combination to anesthetize the skin and underlying soft tissue to increase the comfort of the procedure.

Position

- The patient should be seated upright with the affected arm in a relaxed position. With the patient in a chair with armrests or on a stretcher with the head of the bed elevated and guardrails up, if possible, this ensures that the patient is in a comfortable position to facilitate access to the GH joint. In addition, with the patient seated or lying down, this can be protective and prophylactic against any falls that may occur during a potential vaso-vagal syncopal episode.

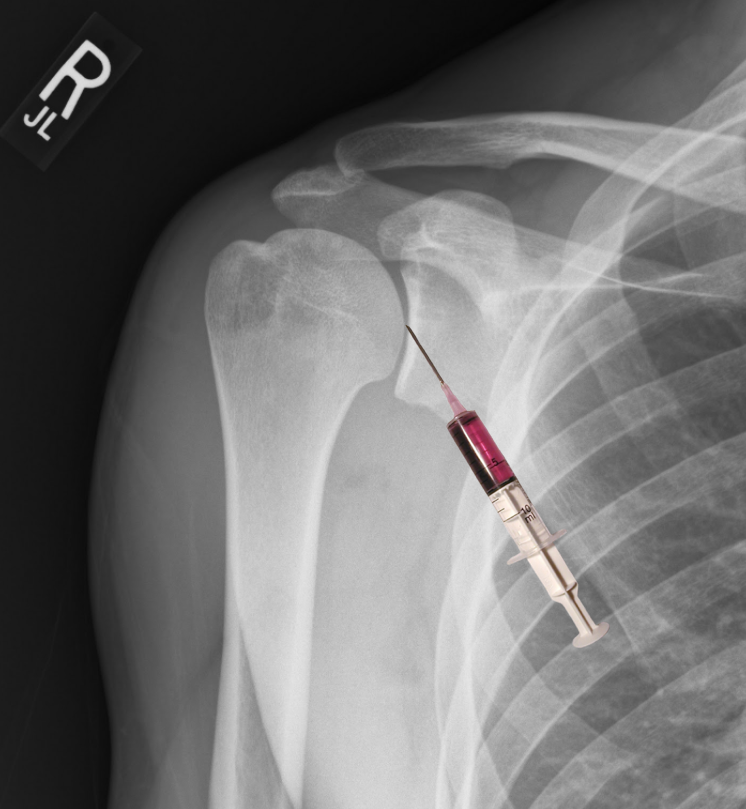

Technique: Anterior Approach

After prepping, sterilizing and draping the skin, the most important step in the shoulder arthrocentesis technique is the proper identification of landmarks which will determine the point of entry into the joint. These landmarks include the humeral head, distal clavicle, and coracoid process. The point of entry is medial to the humeral head and inferior/lateral to the coracoid process. Insert needle perpendicular to the skin and into the joint space as depicted in the figure. If you chose to identify your landmarks prior to the sterilization process, using a skin impression or marking pen at the site of insertion can maintain an accurate position during the prepping and draping of the skin.

While drawing back on the plunger to check for intra-articular blood or synovial fluid. Once the syringe is filled, a hemostat can be placed on the hub of the needle to facilitate the removal of a syringe filled with synovial fluid to be sent for analysis and placement of an additional syringe (if needed) to draw off any additional fluid. This same syringe exchange technique can be used to attach a syringe filled with local anesthetic and or injectable steroids as indicated. The skin is then cleaned, and a bandage is placed.

Technique: Posterior Approach

Utilizing the same preparation technique as noted above, the posterior approach is commonly utilized for aspiration/injection to the GH joint. The entry point is two fingers’ breadth inferior and medial to the palpated posterolateral border of the acromion. The needle is directed anteromedially, with the opposite hand palpating the coracoid process. The coracoid serves as a directional reference point to help guide the clinician's needle trajectory.

Complications

The most important risk to discuss with the patient is an iatrogenic infection. While this complication is rare (approximately 1/10000), it remains a possibility.

- Pain

- Bleeding (from the site and into the joint)

- Damage to surrounding soft tissue (nerves, tendons, etc.)

- Damage to bone or cartilage

Clinical Significance

Joint Fluid Analysis

- Characteristics of normal synovial fluid analysis include clear appearance, WBC count less than 200 cells/microL, PMNs less than 25%, synovial lactate less than 5.6 mmol/L, and glucose levels approximating serum glucose.

- Characteristics of synovial fluid analysis in inflammatory conditions (e.g., osteoarthritis, trauma) include clear/yellow appearance, WBC count less than 2000 cells/microL, PMNs less than 25%, high viscosity, and glucose level approximating serum glucose.

- Characteristics of synovial fluid analysis suggestive septic joint include WBC count greater than 50,000 cells/microL (greater than 1,100 in a prosthetic joint) with greater than 90% PMN (greater than 65% in a prosthetic joint). Additional suggestive findings include synovial lactate greater than 5.56 mmol/L and LDH >250.

- It is important to note that the absence of one or more of these findings does not definitively differentiate reactive and inflammatory arthritis from infection. It is imperative that the gram stain is obtained if there is a suspicion of septic arthritis. If there is an insufficient quantity of synovial fluid to perform all of the recommended testings, Gram stain must be prioritized.

Clinical Pearls

- Needle trauma can damage cartilaginous structures. Avoid hitting the bone.

- The thoracoacromial artery lies medial to the coracoid

- Directing the needle slightly superiorly will help to avoid neurovascular structures.

- The use of ultrasound for joint space identification can increase both procedure safety and success.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Shoulder arthrocentesis is a useful diagnostic and therapeutic technique. However, as with any medical procedure, the keys to success often lie in thorough preparation. Since there are no hyperacute indications for arthrocentesis of the shoulder, adequate preparation time should always be taken to maximize success and to minimize risk. While the procedure may be done by the radiologist or orthopedic surgeon, the patient should be monitored by the nurse during the procedure.